The Pencil of Nature

The Pencil of Nature, published in six installments between 1844 and 1846, was the "first photographically illustrated book to be commercially published"[1] or "the first commercially published book illustrated with photographs".[2] It was wholly executed by the new art of Photogenic Drawing, without any aid whatever from the artist's pencil and regarded as an important and influential work in the history of photography.[3] Written by William Henry Fox Talbot and published by Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans in London, the book detailed Talbot's development of the calotype process and included 24 calotype prints, each one pasted in by hand, illustrating some of the possible applications of the new technology. Since photography was still very much a novelty and many people remained unfamiliar with the concept, Talbot felt compelled to insert the following notice into his book:

The plates of the present work are impressed by the agency of Light alone, without any aid whatever from the artist's pencil. They are the sun-pictures themselves, and not, as some persons have imagined, engravings in imitation.

The cover page for The Pencil of Nature clashed designs, which was characteristic of the Victorian era, with styles inspired by baroque, Celtic, and medieval elements.[4] Its symmetrical design, letterforms, and intricate carpet pages are similar to and a pastiche of the Book of Kells.

The Pencil of Nature was published and sold one section at a time, without any binding (as with many books of the time, purchasers were expected to have it bound themselves once all the installments had been released). Talbot planned a large number of installments; however, the book was not a commercial success and he was forced to terminate the project after completing only six.

Photographs

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Pencil of Nature. |

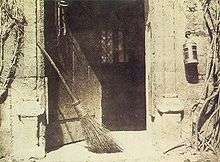

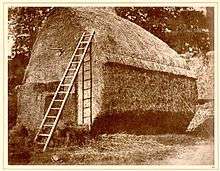

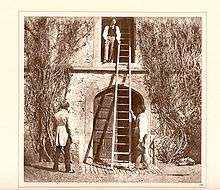

The 24 plates in the book were carefully selected to demonstrate the wide variety of uses to which photography could be put. They include a variety of architectural studies, scenes, still-lifes, and closeups, as well as facsimiles of prints, sketches, and text. Due to the long exposure times involved, however, Talbot included only one portrait, The Ladder (Plate XIV). Though he was no artist, Talbot also attempted to illustrate how photography could become a new form of art with images like The Open Door (Plate VI).

The complete list of plates is as follows:

- Part 1

- I. Part of Queen's College, Oxford

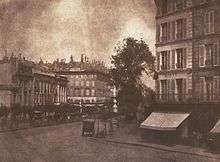

- II. View of the Boulevards at Paris

- III. Articles of China

- IV. Articles of Glass

- V. Bust of Patroclus

- Part 2

- VI. The Open Door

- VII. Leaf of a Plant

- VIII. A Scene in a Library

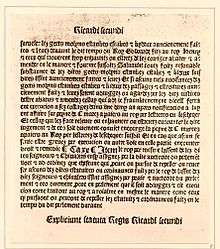

- IX. Fac-simile of an Old Printed Page

- X. The Haystack

- XI. Copy of a Lithographic Print

- XII. The Bridge of Orléans

- Part 3

- XIII. Queen's College, Oxford: Entrance Gateway

- XIV. The Ladder

- XV. Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire

- Part 4

- XVI. Cloisters of Lacock Abbey

- XVII. Bust of Patroclus

- XVIII. Gate of Christchurch

- Part 5

- XIX. The Tower of Lacock Abbey

- XX. Lace

- XXI. The Martyrs' Monument

- Part 6

- XXII. Westminster Abbey

- XXIII. Hagar in the Desert

- XXIV. A Fruit Piece

Text

Each plate is accompanied by a short text which describes the scene and the photographic processes involved in obtaining it. Talbot emphasized the practical implications of his images (for instance, "The whole cabinet of a Virtuoso and collector of old China might be depicted on paper in little more time than it would take him to make a written inventory describing it in the usual way."), but he also recognized their artistic value ("The chief object of the present work is to place on record some of the early beginnings of a new art, before the period, which we trust is approaching, of its being brought to maturity by the aid of British talent.")

Due to the novelty of the subject, Talbot needed to point out some things that seem obvious today; for instance, "Groups of figures take no longer time to obtain than single figures would require, since the Camera depicts them all at once, however numerous they may be." He also speculated about such questions as (among others) whether photographs would stand up as evidence in court and whether a camera could be made to record ultraviolet light.

At the beginning of the book, Talbot included an incomplete history of his development of the calotype, titled "Brief Historical Sketch of the Invention of the Art." The history ends rather abruptly, and though Talbot expressed his intention to complete it at a later date, he never did.

Editions

Only about 15 complete copies of the original 1844-1846 edition still exist. At least two facsimile editions have been issued:

- New York: Da Capo Press, 1969.

- New York: Hans P. Kraus, Jr., 1989. ISBN 0-9621096-0-6

- Bath: Monmouth Calotype 1989

References

- Glasgow University Library, Special Collections Department. Book of the month. February 2007. William Henry Fox Talbot. The Pencil of Nature. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- William Henry Fox Talbot: The Pencil of Nature (1994.197). In Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/33447/33447-pdf.pdf

- Meggs, Philip B., Purvis, Alston W. "Graphic Design and the Industrial Revolution" History of Graphic Design. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2006. p.152-153.