The Oxen and the Creaking Cart

The Oxen and the Creaking Cart is a situational fable ascribed to Aesop and is numbered 45 in the Perry Index.[1] Originally directed against complainers, it was later linked with the proverb ‘the worst wheel always creaks most’[2] and aimed emblematically at babblers of all sorts.

The fable

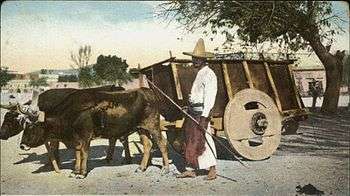

The Greek fabulist Babrius collected two variant fables that told of oxen straining to pull a laden wagon with creaking wheels. In one the oxen reprove the cart for complaining when it is they who have the heaviest work to do.[3] In the other, it is the angry waggoner who points this out.[4]

When the situation began to be related in English collections, however, there were significant changes. In Roger L'Estrange’s version (1692), titled simply “A Creaking Wheel”, it is “the worst wheel of the four” that justifies the noise it makes by pointing out that “They that are Sickly are ever the most Piping and Troublesome”.[5] In Samuel Croxall’s collection of 1722, the worst wheel of a coach remarks that “it was natural for people who laboured under any affliction or infirmity to complain”.[6] It was not until George Fyler Townsend’s new translation of 1867 that the original Greek fable was returned to under the title “The Oxen and the Axle-Trees”.[7]

What had intervened was a Latin fable in the Hecatomythium (1495) of Laurentius Abstemius with this worst wheel variation.[8] Abstemius often concocted such fables to fit current proverbs and the one he had in mind in this case was recorded a century before him in France as Toujours crie la pire roue du char (It’s always the cart's worst wheel that complains).[9] The proverb persisted into the Renaissance and beyond in various European languages.[10] It also reappeared at the end of a poem by Gilles Corrozet that accompanied an emblem criticising babblers.[11]

The fables of Abstemius were often reprinted and began to be added to general collections of fables translated into Latin, of which the bulk were by Aesop. In this way his work was later ascribed to Aesop himself and the creaking wheel version was mistaken for an additional variant of those recorded by Babrius fifteen centuries previously.

References

- Aesopica

- The Wordsworth Dictionary of Proverbs, p.650

- Rev. John Davies, Fables of Babrius translated into English Verse, Fable 11

- Fable 52

- Fables of Aesop and other Eminent Mythologists, Fable 336

- The Fables of Aesop, with instructive applications, Fable 112

- Fable 34

- De auriga et rota currus stridente, Fable 84

- Guiot de Provins, La Bible satirique, line 37

- François Coppée, Proverbes d’autrefois (Paris 1903), pp.87-8

- Emblemes in Cebes (1643), Emblem 65