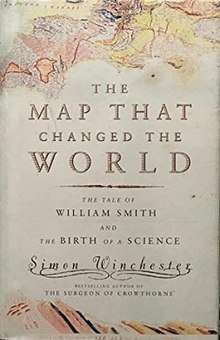

The Map that Changed the World

The Map that Changed the World is a 2001 book by Simon Winchester about English geologist William Smith and his great achievement, the first geological map of England, Wales and southern Scotland.

Smith's was the first national-scale geological map, and by far the most accurate of its time. His pivotal insights were that each local sequence of rock strata was a subsequence of a single universal sequence of strata and that these rock strata could be distinguished and traced for great distances by means of embedded fossilized organisms.

Winchester's book narrates the intellectual context of the time, the development of Smith's ideas and how they contributed to the theory of evolution and more generally to a dawning realisation of the true age of the earth. The book describes the social, economic or industrial context for Smith's insights and work, such as the importance of coal mining and the transport of coal by means of canals, both of which were a stimulus to the study of geology and the means whereby Smith supported his research. Land owners wished to know if coal might be found on their holdings. Canal planning and construction depended on understanding the rock and soil along its route.

Related topics, such as the founding of the Geological Society of London, are included. Smith's map was published by John Cary, a leading map publisher. Winchester describes the practice of publishing at the time as well as the system of debtor's prisons through his account of the sojourn of Smith in the King's Bench Prison.

Book format details

The Map that Changed the World was published in 2001 by Harper Collins, while Winchester retains the copyright. The first edition is illustrated by Soun Vannithone. It includes an extensive index, glossary of geological terms, recommended reading and (lengthy) acknowledgements, as well as many stippled images (of consistent style). The last numbered page is page 329. There are 16 chapters, and single clay paper sheet in the middle containing colour plates of Smith's famous map and a modern geological map for comparison. (Smith's map is less complete, but essentially in agreement with the modern map). An image of Smith's first table of strata, and first (circular) geological map are also included. Just after the contents section, there is a 5-page section giving extensive details on the illustrations (such as the names of the chapter heading fossils). Each chapter begins with an inset image of a fossil, and a large first Capital. The dust-cover of the book can be removed and unfolded to reveal a larger print of the map in question.

The contents

One: Escape on the Northbound Stage

Two: A Land Awakening from Sleep

Three: The Mystery of the Chedworth Bun

Four: The Duke and the Baronet's Widow

Five: A Light in the Underworld

Six: The Slicing of Somerset

Seven: The View from York Minster

Eight: Notes from the Swan

Nine: The Dictator in the Drawing Room

Ten: The Great Map Conceived

Eleven: A Jurassic Interlude

Twelve: The Map That Changed the World

Thirteen: An Ungentlemanly Act

Fourteen: The Sale of the Century

Fifteen: The Wrath of Leviathan

Sixteen: The Lost and Found Man

Seventeen: All Honor to the Doctor.

Escape on a Northbound Stage

A plausible but whimsical description of the day on which William Smith was let out of debtor's prison. It inducts the reader into the interpretation of the time and place to be held consistently throughout the book. Smith is described physically, as heavy-set balding and plain-looking, and emotionally as quitting London in disgust. He is leaving London with nothing other than his wife, nephew, and such possessions as they can carry. It is implied that these circumstances are the result of unjustified discrimination from the scientific elite. The chapter ends with a brief note that 12 years later the injustice was in some measure redressed.

A Land Awakening from Sleep

A description of the social circumstances of the time of the birth of Smith. It begins by emphasising that the date of 4004 bc, for the beginning of the world, computed from the genealogy tables of the bible, was firmly accepted by most; the idea that the world was any older was considered implausible. Explanations based on Noah's flood were acceptable in scientific circles. But, in the year 1769, as Smith was born, James Watt was patenting a steam engine, cloth manufacture was improving, the postal service was viable. New technology and information was rapidly becoming available or even common-place. "William Smith appeared on the stage at a profoundly interesting moment: he was about to make it more so."

These claims by Winchester are inaccurate. Geologists had begun to recognize that the earth was old in the late 1600s. Ussher's 4004 BC age for the earth, along with similar estimates by Isaac Newton and other academics of the 17th century, was merely a historical footnote in academia by Smith's lifetime. In 1787, Scottish geologist James Hutton argued that the earth's age was immeasurable.[1] Smith was in no way challenging the church or risking jail - American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould refuted such claims in his review of The Map That Changed the World.[2] In fact, Smith's single-minded focus on recognizing layers made him rather late to realize that the earth was old. Additionally, Smith's focus on recognizing layers based on the fossils in them was not unique. Though he was especially thorough, similar work (especially on the mainland of Europe) around the same time independently cemented the principle that fossils change over time and can be reliably used to identify layers. Martin Rudwick's Earth's Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters is perhaps the most accessible account of the development of geology in this time interval.

Footnotes

- Kenneth L. Taylor (September 2006). "Ages in Chaos: James Hutton and the Discovery of Deep Time". The Historian (abstract). Book review of Stephen Baxter. ISBN 0-7653-1238-7. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2001-10-04). "The Man Who Set the Clock Back". The New York Review of Books. 48 (15): 51–6. Retrieved 29 August 2018.