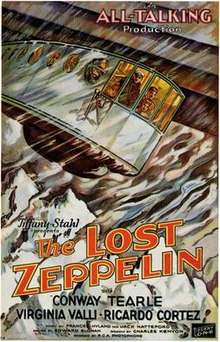

The Lost Zeppelin

The Lost Zeppelin is a 1929 sound adventure film directed by Edward Sloman and produced and distributed by Tiffany-Stahl.[1] The film stars Conway Tearle, Virginia Valli and Ricardo Cortez.[2][3]

| The Lost Zeppelin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Edward Sloman |

| Produced by | Tiffany-Stahl |

| Written by | Jack Natteford (story) (as John Francis Natteford) Frances Hyland (adaptation) Charles Kenyon (dialogue) |

| Starring | Conway Tearle Virginia Valli Ricardo Cortez |

| Music by | Meredith Willson |

| Cinematography | Jackson Rose |

| Edited by | Martin G. Cohn W. Donn Hayes (as Donn Hayes) |

Production company | Tiffany-Stahl Productions |

| Distributed by | Tiffany Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 8 reels |

Tearle plays a navy officer modeled on U. S. Navy Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd who was then a national aviation hero.[4] Byrd made his own genuine Antarctic adventure With Byrd at the South Pole film during his South Pole Expedition 1928-1929.[5]

Plot

At a banquet preceding his flight to the South Pole, Commander Donald Hall (Conway Tearle), a Zeppelin commander in charge of the "Explorer", learns that his wife, Miriam (Virginia Valli), whom he worships, requests a divorce. She is in love with Lieutenant Tom Armstrong (Ricardo Cortez), his best friend and partner in the flight. Hall agrees to grant the divorce after the flight.

When the Zeppelin reaches the South Pole, a sudden gale causes it to crash and the men divide up into search parties. An aircraft with room for only one survivor leads to a decision by Hall that Armstrong should be the one to be saved.

Armstrong is welcomed in Washington as the only survivor but finds that Miriam still loves her husband. Later, news comes of Hall's rescue and miraculous recovery, and he is happily reunited with his wife.

Cast

- Conway Tearle as Commander Donald Hall

- Virginia Valli as Miriam Hall

- Ricardo Cortez as Tom Armstrong

- Duke Martin as Lieutenant Wallace

- Kathryn McGuire as Nancy

- Winter Hall as Mr. Wilson

uncredited

- Richard Cramer as Radio Announcer

- Ervin Nyiregyhazi as Pianist

- William H. O'Brien as Radio Operator

Production

The stagey early part of The Lost Zeppelin was dominated by a banquet scene and actors engaged in dialogue from static positions. [N 1] The "shoddy production" values described by aviation film historian Michael Paris in From the Wright Brothers to Top gun: Aviation, Nationalism, and Popular Cinema (1995) were typical of the early sound film era.[6]

The Zeppelin in The Lost Zeppelin is recreated in stock footage of flights, and the use of miniatures as well as a mockup of the gondola. Although technically, the special effects were satisfactory for the era, aviation film historian James H. Farmer in Celluloid Wings: The Impact of Movies on Aviation (1984) considered The Lost Zeppelin had "disappointing special effects and triangular plot."[7]

Reception

Mordaunt Hall in his review for The New York Times gave a mostly negative review of The Lost Zeppelin, "Presumably the producers of "The Lost Zeppelin," an audible pictorial melodrama now at the Gaiety, do not believe in a very high order of intelligence among cinema audiences, for the best that can be said of the film is that it appears to have been fashioned with a view to appealing to boys from 8 to 10 years of age. Several such youngsters were at the first showing of this offering last Saturday afternoon, and they became volubly enthusiastic over the Antarctic blizzard, the far from impressive airship, the artificial ice fields and the clumsily designed chain of incidents."[8]

Preservation status

The Lost Zeppelin is listed as "preserved" in the Library of Congress database.[9] The film has also been released on Alpha DVD.[10]

See also

- With Byrd at the South Pole (1929)

- Dirigible (1931)

References

Notes

- The early sound equipment was difficult to use and actors often had to deliver lines "on their marks", afraid to even turn their heads and lose microphone coverage.

Citations

- "Detail view: 'The Lost Zeppelin'." The AFI Catalog of Feature Films2019. Retrieved: July 12, 2019.

- Catalog of Holdings The American Film Institute Collection and The United Artist Collection at The Library of Congress. Los Angeles: The American Film Institute, 1978, p. 107.

- Wynne 1987, p. 173.

- Pendo 1985, p. 298.

- "Data:'The Lost Zeppelin'." silentera.com, 2019. Retrieved: July 12, 2019.

- Paris 1995, p. 111.

- Farmer 1984, P. 319.

- Hall, Mordaunt. "The screen." The New York Times, February 3, 1930. Retrieved: July 12, 2019.

- "American Silent Feature Film Survival Catalog:'The Lost Zeppelin'." The Library of Congress, 2019. Retrieved: July 12, 2019.

- "View: 'The Lost Zeppelin'." Alpha Video DVD, 2019. Retrieved: July 12, 2019.

Bibliography

- Farmer, James H. Celluloid Wings: The Impact of Movies on Aviation (1st ed.). Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania: TAB Books 1984. ISBN 978-0-83062-374-7.

- Paris, Michael. From the Wright Brothers to Top gun: Aviation, Nationalism, and Popular Cinema. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-7190-4074-0.

- Pendo, Stephen. Aviation in the Cinema. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1985. ISBN 0-8-1081-746-2.

- Wynne, H. Hugh. The Motion Picture Stunt Pilots and Hollywood's Classic Aviation Movies. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1987. ISBN 0-933126-85-9.

External links

- The Lost Zeppelin at IMDb.com

- The Lost Zeppelin at AllMovie

- The Lost Zeppelin available for free download @ Internet Archive