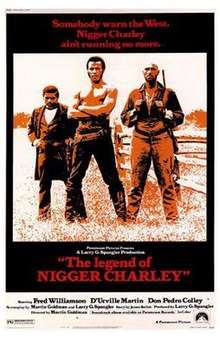

The Legend of Nigger Charley

The Legend of Nigger Charley is a 1972 blaxploitation western film directed by Martin Goldman. The story of a trio of escaped slaves, it was released during the heyday of blaxploitation films. It was filmed in Charles City, Virginia and Eve's Ranch, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Other film locations included Jamaica and Arizona. The movie covers themes of racism, romance, and self-determination. The movie received backlash for its controversial title.[3]

| The Legend of Nigger Charley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Martin Goldman |

| Produced by | Larry G. Spangler[1] |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | James Bellah[1] |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Bennings[2] |

| Cinematography | Peter Eco[2] |

| Edited by | Howard Kuperman[2] |

Production company | Spangler & Sons Pictures[2] |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures Corp. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States[2] |

The film stars Fred Williamson as Nigger Charley. The film is rated PG in the United States. It was followed by a 1973 sequel, The Soul of Nigger Charley. The film was renamed The Legend of Black Charley for broadcast television.[4]

Plot

The opening scene includes Charley as a baby with his mother Theo in Africa. The two are forced into slavery. Twenty years later, Charley kills an abusive plantation owner and flees with his two friends, Joshua and Toby. As they run away from the slave catchers, the trio experience racism, standoffs and romance, specifically in a small town. After Joshua is killed in a standoff against the town's outlaw, the film ends with Charley and Toby leaving the town to continue traveling with no destination. According to the reviewer in the New York Times, "For all the feverish activity, there has yet to be a film of rounded merit—one of skill, imagination and impact—about the black man and the Old West. Sadly, The Legend of Nigger Charley is fair. Fair only."[5]

Cast

- Fred Williamson as Nigger Charley

- D'Urville Martin as Toby

- Don Pedro Colley as Joshua

- Thomas Anderson as Shadow

- Jerry Gatlin as Sheriff Rhinehart

- Alan Gifford as Hill Carter

- Will Hussung as Dr. Saunders

- Gertrude Jeannette as Theo

- Fred Lerner as Ollokot

- Marcia McBroom as Leda

- Bill Moor as Walker

- Tricia O'Neil as Sarah Lyons

- John Ryan as Houston

- Doug Row as Dewey Lyons

- Joe Santos as Reverend

Background

This film was the debut movie for commercial director Martin Goldman. However, after many disagreements with the producer, Goldman distanced himself from the production. Larry Spangler, the producer, envisioned the film. To assure a degree of accuracy, he spent months researching that period during the 1800s. At first, Woody Strode was cast in the lead role but Strode changed his mind and dropped out. When Spangler continued the process of casting, he saw several top actors. However, he chose Williamson for "his right stature, the feel, the stamina, fervor, and virility of Nigger Charley ..." Fred Williamson at that point had never shot a gun or been on horse. He spent a total of one week working on both skills. Spangler wanted an authenticity to the setting. Thus, they filmed at an actual plantation, Shirley Plantation, in Virginia. Shirley Plantation was actually owned by the Carter family. This plantation is known for being the birth spot of General Robert E. Lee, the leader of the Confederate forces in the Civil War.[6]

Race and racism

When the film first advertised, the film promised black men fighting Indians. The advertisement and plot line caused a backlash from the Native Americans. They protested their depiction. Specifically, there is a scene in the film where Charley, Toby and Joshua run into a group of Native Americans. They approach the trio and begin to touch their skin trying to see whether the black color would rub off. This was extremely offensive to the Native American community and many chose to send letters. This is why the production was moved from Colombia to New Mexico.

However, most of the controversy was centered on the title of the film. Some found the name so offensive that the newspapers actually edited the name in the advertisements to The Legend of Black Charley, or just Black Charley. Williamson said, "I called it Nigger Charley because it was controversy. The word nigger in the '70s was hot. Controversy is what sells." [7] He later explained that he believed the movie was helping to take back the meaning from the historical defamation. The movie helps reinforce the expected interaction between black and white people regarding the racial slur. White characters were chastised and punished for using the word while black people were free to use it flippantly. Throughout the film, they say it as a badge of honor, "signifying their willingness to defy the paralyzing constrictions of white society." This paradigm is a reflection of what was occurring at the time regarding who was "allowed" to say the "N word."

In response to the controversy, Don Pedro Colley stated that racism is just a part of life and trying to cover up that point of history would be pointless. He also mentioned that he viewed the film as the black Indiana Jones and felt that the media was sensationalizing the film to be more controversial than the movie truly is.[8]

Film reviews

The film received rather negative reviews.[1] From contemporary reviews, David McGillivray of the Monthly Film Bulletin reviewed a 95 minute version of the film.[2] McGillivray stated that the film was "a routine amalgam of all the current 'black film' cliches" specifically noting the "blithely anarchronistic score sounds like a nightclub jam session, though it is also all of a piece with the film's grand disregard for authenticity."[2] McGillivray declared that "the scriptwriters seem hard put to find anything for their ox-like hero to do, and appear content to fill in the space between battles with monotonous and generally irrelveant dialogue exchanges between subsidiary characters."[2]

The Philadelphia Tribune stated, "The Legend of Nigger Charley which opened at the Goldman Theater Wednesday, may not be the worst picture I've seen, but offhand I can't think of any that can top it." The review goes on to explain how some of the atrocity of the film can be due to the genre it belongs to: Blaxploitation. This review said that this film and other Blaxploitation films insulted Black moviegoers' intelligence. The opening scene, described as "nonsensical," is thought to be an empty shot at showing nudity rather than an accurate and insightful depiction of Africa. Furthermore, this reviewer didn't look kindly on the representation of the kind white plantation owner who freed Charley. The language in this review was patronizing and condescending to the image, "Then we jump to the story about Nigger Charley, a pre-Civil War slave who is freed by dear old massa on his deathbed thanks to the pleading of his kindly old momma." Once again, the reviewer criticizes the exchange between another Charley and Leda as the inclusion of a pointless sex scene void of any plot significance. He considers the occasions of blood and gore for the sake of Black audience praise a cheap and insulting tactic. The humor was poor and the dialogue inane. Overall, Len Lear considered this film to be a terrible exploitation film.[9]

The Boston Globe also had malicious words for the film, calling it "a racist Western." Although there are black characters in the film, the film remains cliché, he states. However, this reviewer affirmed the movie's values by stating that the meaning would be different if viewed as a black child. The movie offers a different hero to look up to for, at the time, there were only white cowboys to emulate during children's make-believe play. The film flips traditional tropes on their heads, as all of the black men are good and courageous in contrast to the white people of the film who are mostly detestable. As far as the acting goes, this reviewer stated that the actors either overacted or "walk woodenly through their roles."[10]

See also

References

- "The Legend of Nigger Charley". American Film Institute. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- McGillivray, David (August 1973). "Legend of Nigger Charley, The". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 40 no. 475. British Film Institute. p. 171.

- "The Legend of Nigger Charley". Proquest. The American Film Institute. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Internet Movie Database. "The Legend of Nigger Charley". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- Thompson, Howard (May 18, 1972). "The Legend of Nigger Charley". The New York Times.

- Gibson, Gertrude (June 1, 1972). "The Legend of Nigger Charley". Los Angeles Sentinel.

- Asim, Jabari (2007). The N Word: Who Can Say It, who Shouldn't, and why. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 182–184.

- Cones, John W. (2007). Patterns of Bias in Hollywood Movies. Algora Publishing. pp. 97–99.

- Lear, Len (May 30, 1972). "'The Legend of Nigger Charley' a Very Poor Exploitation Film". Philadelphia Tribune.

- McKinnon, George (June 17, 1972). "'Nigger Charley'/ film review". Boston Globe.