The King of the Cats

The King of the Cats (or The King o' the Cats) is a folk tale from the British Isles.[1] The earliest known example is found in Beware the Cat, written by William Baldwin in 1553,[nb 1] though it is related to the first century story of "The Death of Pan". Other notable versions include one in a letter written by Thomas Lyttelton, 2nd Baron Lyttelton, first published in 1782,[nb 2] M. G. Lewis told the story to Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1816, and a version was adapted by Joseph Jacobs from several sources, including one collected by Charlotte S. Burne.[2][3][4] Walter Scott reported that it was a well known nursery tale in the Scottish Highlands in the eighteenth century.[5] It can be categorised as a "death of an elf (or cat)" tale: Aarne–Thompson–Uther type 113A, or Christiansen migratory legend type 6070B.[6]

Summary

A man travelling alone sees a cat (or hears a voice), who speaks to him, saying to tell someone (often an odd name, presumably unknown to the character[nb 3]) that someone else (normally a similarly odd name[nb 4]) has died, though other versions simply have the traveller see a group of cats holding a royal funeral. He reaches his destination and recounts what happened, when suddenly the housecat cries something like "Then I am the king of the cats!", rushes up the chimney or out of the door, and is never seen again.[6]

Folk tradition

In William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, Tybalt is referred to by Mercutio as "Prince of Cats", and though this is more likely in reference to Tibert/Tybalt the "Prince of Cats" in Reynard the Fox, it demonstrates the existence of the phrase from at least the 16th century in England.

Beware the Cat, written in 1553 and first published in 1561, known as the first horror fiction text longer than a short story and possibly the first novel (or is that "novella"?) ever published in English, contains two traditional tales about cats, which appear in similar forms both before and after its publication; of which "The King of the Cats" is a notable example.[7]

A king or lord of the cats appears in at least two early Irish tales. Most notably, some versions of the Imtheacht na Tromdhaimhe (The Proceedings of the Great Bardic Institution) include a dispute between Senchán Torpéist the bard and king Guaire Aidne mac Colmáin of Connacht, which led to the bard first cursing all mice, killing a dozen of them in shame, followed by the cats who should have kept the mice in check; in retaliation, the king of the cats, Irusan son of Arusan hunts Senchán down intending to kill him, but is in turn killed by St Kieran.[8] This tale was reworked by Lady Jane Wilde as "Seanchan the Bard and the King of the Cats", published in her 1866 book Ancient Legends of Ireland, and included in W. B. Yeats' 1892 book Irish Fairy Tales. The second was retold as "When the King of the Cats Came to King Connal's Dominion" in Padraic Colum's 1916 book The King of Ireland's Son.

Cats are connected in many folklore traditions with the supernatural and supernatural beings such as elves and fairies.[6]

Influence

The story was mentioned in Henrietta Christian Wright's 1895 book Children's Stories in American Literature.

On the death of Algernon Charles Swinburne in 1909, W. B. Yeats (then 38 years of age) was reported to have declared to his sister "I am king of the cats."[9]

Polish-French modern artist Balthus inscribed his 1935 self-portrait "A Portrait of H.M. The King of the Cats Painted by Himself."[10]

Stephen Vincent Benét's 1929 short story "The King of the Cats" based around this folk story was selected by The Library of America for inclusion in its two-century retrospective of American Fantastic Tales, edited by Peter Straub.

Frances Jenkins Olcott's 1942 anthology Good Stories For Great Holidays included a version of Charlotte S. Burne's "The King of the Cats" adapted by Ernest Rhys.

Barbara Sleigh's 1954 children's book Carbonel: The King of the Cats is inspired in part by this tale, as are its two sequels, The Kingdom of Carbonel and Carbonel and Callidor, which make up the Carbonel series.[11]

Paul Galdone published a children's picture book in 1980 titled King of the Cats.[12]

In John Crowley's 1987 novel The Solitudes, "The King of the Cats" is explicitly related to "the Death of Pan" as recorded by Plutarch and interpreted by St. Augustine of Hippo as a shift in World Ages.

China Miéville takes the idea of a king of the cats from this story and Robert Irwin's "Father of Cats" from The Arabian Nightmare for his 1998 novel King Rat.[13]

American author P. T. Cooper's 2012 middle-grade children's novel, The King of the Cats, starts off with a retelling of the original legend but then picks up where the legend left off. The novel tells of the death of Tom Tildrum and the crowning of his successor, Jack Tigerstripes, who is told by a feline oracle on his coronation day that he is destined to be captured by a human and to end his life in exile. The resulting 217-page adventure is reminiscent of a Disney-style talking-animal story such as The Lion King.[14]

The title track of American rock band Ted Leo and the Pharmacists' 2003 EP "Tell Balgeary, Balgury Is Dead" was inspired by a County Cork version of "The King of the Cats", with the title referring to the cats' names in the story, and mention in the song of the story's setting, the graveyard at Inchigeelagh.[15]

Kim Newman's novella Vampire Romance (2012) has a group of vampire elders gathering after the downfall of Count Dracula to decide which one of them will become the next "King of the Cats"; the story explicitly refers to the Tom Tildrum folk tale.

This legend is referenced in the manga/anime, The Ancient Magus' Bride (chapters 4–7/episodes 4–5): A cat, named Molly, is the current King of the Cats, and the first King is called "Tim".

The story is referenced in the videogame Ni No Kuni where the kingdom of Ding Dong Dell is ruled by an anthropomorphic cat named King Tom Tildrum XIV. His counterpart in the human world is a housecat named Timmy Toldrum.

See also

- Cultural depictions of cats

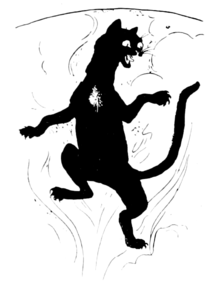

- Cat Sìth, a cat from Scottish and Irish mythologies that was black with a white spot on its chest

Notes

- The version found in Beware the Cat follows the same plot, but does not use the phrase "King of the Cats".

- The Lyttelton letter is the first known version to have the cat claim it is "King of the Cats".

- Such as Titton Tatton, Dildrum, Tom Tildrum, Balgeary, Maud or Moll Browne.

- Such as Grimmalkin, Doldrum, Tim Toldrum, Balgury, Maudlin or Tom Dunne.

References

- Folk Tales of the British Isles

- "Journal at Geneva: 'Ghost Story No. IV'" Lewis, M. G., quoted by Shelley, P. B. in Journal at Geneva (including Ghost Stories) and on Return to England, 1816. (ed. Mrs. Shelley, 1840)

- Joseph Jacobs, More English Fairy tales, p. 156–8 (tale 74); notes.

- "Two Folk-tales from Herefordshire: 'The King of the Cats'" Burne, C. S.,The Folk-Lore Journal. Volume 2, 1884.

- Scott, Walter, The poetical works of Walter Scott, Vol. 6, Edinburgh: Arch. Constable and co., 1820, p. 107, note.

- D. L. Ashliman, "Death of an Underground Person: migratory legends of type 6070B"

- Schwegler, Robert A., "Oral Tradition and Print: Domestic Performance in Renaissance England" in The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 93, No. 370, Oct.–Dec. 1980, p. 440

- Connellan, Owen "The Proceedings of the Great Bardic Institutions" in Transactions of the Ossianic society for the years, 1853–1858, vol. 5, pp.80–85

- Kiely, Kevin, "King of the Cats" in Books Ireland, No. 261, Oct. 2003, p. 234

- Thrall Soby, James, "Balthus" in The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 24, No. 3, 1956–1957, p.3

- The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales by Donald Haase

- Paul., Galdone (1980). King of the Cats : a ghost story. Jacobs, Joseph, 1854-1916. New York: Houghton Mifflin/Clarion Books. ISBN 0395290309. OCLC 5171415.

- Gordon, Joan and Miéville, China, "Reveling in Genre: An Interview with China Miéville" in Science Fiction Studies Vol. 30, No. 3, Nov. 2003, p. 361

- Cooper, P. T. (2012). The King of the Cats. p. 217. ISBN 978-0615651057.

- Hartwell, Sarah Old Cat Stories from Around the World

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Briggs, Katherine M., A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales in the English Language 2 Vols., Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1971, Vol. 1 pp. 291–295

- Hudson, Arthur Palmer, "Some versions of 'The King of the Cats'", in Southern Folklore Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 4, Dec. 1953

- Maynard, Lara, The King of the Cats: Reassessing the Criterion of Orality with a Case Study in Textual Transmission, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1995

- Ó Néill, Eoghan Rua, "The King of the Cats (ML 6070B): The Revenge and the Non-Revenge Redactions in Ireland" in Béaloideas, Iml. 59, The Fairy Hill Is on Fire! Proceedings of the Symposium on the Supernatural in Irish and Scottish Migratory Legends, 1991

- Taylor, Archer, Northern Parallels to the Death of Pan, University of Minnesota, 1922