The Hobby Horse

The Hobby Horse was a quarterly Victorian periodical in England published by the Century Guild of Artists. The magazine ran from 1884–1894 and spanned a total of seven volumes and 28 issues. It featured various articles not only on arts and design but other subjects including literature and social issues as well. It also featured artwork such as sketches, plates, photographs, engravings, wood cuts, lithographs and reproduced paintings.[2]

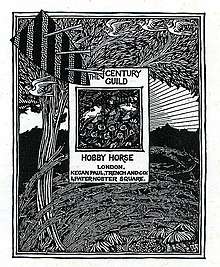

Sample Issue of the Century Guild Hobby Horse[1] | |

| Editor | Herbert Horne |

|---|---|

| Former editors | Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo |

| Publisher | Chiswick Press |

| First issue | Apr 1884 |

| Final issue Number | Oct 1894 Issue 28 |

The Hobby Horse started publication in 1884 as the first high quality magazine committed solely to the visual arts.[3] The Century Guild Hobby Horse "was one of the last (and in many ways the ultimate) versions of the literature and art journal, a genre born with the Pre-Raphaelite Germ in 1850. Unlike its successors, The Yellow Book and The Savoy, The Hobby Horse was not solely committed to an elite aestheticism. Its pages were filled with essays arguing for recognition of the vital social role of art and artists." [4] The Century Guild Hobby Horse was a magazine for the most dedicated of art enthusiasts at the time, a magazine that helped cement what purpose art served in the English Victorian community. The contributors looked at art from a scholarly perspective, one that set the blueprints for how art is seen today. The magazine was an idealistic vision to create unity in the arts.[4]

History

The Century Guild of Artists was an English group of art enthusiasts that were most active between 1883 and 1888. It was founded in 1882 by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, and was influenced by the likes of William Morris, John Ruskin, Matthew Arnold, Walter Pater. The Century Guild also drew many of their ideas from the growing Arts & Crafts Movement, the Pre-Raphealites, the Decadent movement and the new Aestheticism.[5]

The Century Guild aimed to preserve the artistic trade and the authenticity of the craftsmen behind it. In 1884 the Century Guild created a journal called The Century Guild Hobby Horse to publicize their views. The magazine was titled The Century Guild Hobby Horse during its publication from 1884–1892, but in its final years in 1893 and 1894 it was simply The Hobby Horse. The Hobby Horse served as a way of sharing the views of the Guild and promoted crafted art as opposed to mechanical industry. The Century Guild disbanded once members Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, Herbert Horne and Selwyn Image became busy with their individual work. Though The Hobby Horse managed to exist longer after the Guild fell apart (and was even titled as just The Hobby Horse), it ultimately was soon to cease production without the Guild in force.[6]

Roughly 20 people had been involved with the Guild but its only members were Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (founder of the Century Guild), Herbert Horne (editor of the Hobby Horse), and Selwyn Image (co-founder of the Century Guild and co-editor of the Hobby Horse). Contributors to the magazine also included William de Morgan, Oscar Wilde and C.F.A. Voysey.[7]

Overview/design

All forms of art and design at the time were addressed in the magazine, including but not limited to classical painting, classical sculpture, literature, poetry, architecture, furniture, and decoration. The magazine also disseminated sensory values of Art Nouveau, specifically elements of the Arts and Crafts Movement which stressed the rebirth of the organic and lifelike aura in the designs and illustrations to overcome the mechanical and lifeless aesthetics influenced by the Industrial Revolution. This kind of high-end selective art was prominent in the Hobby Horse.

The Hobby Horse aimed to champion the philosophy and aims of the Century Guild and was carefully produced under the tutelage of Emery Walker (1851–1933), the renowned printer and typographer at the Chiswick Press.[6] "The exceptional quality of Hobby Horse accounted for the relatively high cost of each issue. Its paper was rag and its binding of the finest quality. Technological innovations in the printing trade, particularly in the areas of photography and reproduction of art and illustrations, were applied. Hobby Horse used the photogravure technique to reproduce everything from Italian Renaissance woodcuts to Pre-Raphaelite painting."[4] The fine production values correlated to the academic writings in the magazine.

The Hobby Horse was crafted using handmade paper and printed lithographs. But the production of The Hobby Horse was not only concerned with design but also typography, layout, and margins. The Century Guild addressed typography as an art form as well. Important to the typographic design was the kerning, leading between lines, and typeface choice.[6] An example of a typeface in the journal was Caslon old-face. It is a medieval typeface that is not found on commercial machine presses. Wide space was used around text to stress the blank white space around the text. Everything about the book was made to look beautiful, this was not meant to be a disposable journal, but rather one to be kept and cared for.[8] It was a book created as an object- the quality of it emphasized the importance of what it represented.

Legacy

The Hobby Horse was "the first 1880s periodical to introduce the British Arts & Crafts viewpoint to a European audience and to treat printing as a serious design form." [6] The Hobby Horse was revolutionary- the printing techniques that were used were ahead of their time and were what helped art enter, survive and even flourish in the industrial world. Despite the desire of many contributors in the Century Guild to keep art distinctive and alive on its own, the Hobby Horse's state of the art production instead helped transition art into the age of mechanical reproduction.

The Hobby Horse was "the harbinger of the growing Arts & Crafts interest in typography, graphic design, and printing." [6]

The Hobby Horse helped set the blueprints for how art is seen today. The contributors majorly attributed to the Arts & Crafts Movement- which influenced almost all art forms at the time. The design of the era incorporated simple motifs to express a more dynamic product. Through this, print design became recognized as a fine art status. Print started to show itself as more than a form of easy production and advertisement, it was also artistic. Print art design gained an intellectual following starting with contributors of the Hobby Horse.

The Hobby Horse was succeeded by magazines like The Yellow Book and The Savoy. These are both quarterly periodicals from London in the vein of the Hobby Horse.

Just like the Hobby Horse, The Yellow Book discusses artistic aestheticism. It even has some of the same contributors as the Hobby Horse, as well as the same publisher. The Yellow Book in a way replaced the Hobby Horse, because publishers invested in favor of the Yellow Book.[9]

Gallery

Hobby Horse prints

References

- Meggs & Purvis 2006, p. 170

- Mackmurdo & Horne 1884

- Meggs & Purvis 2006, p. 169

- Codell, Julie F. 1983, p. 43

- Sloan, John 2003, p. 73

- Meggs & Purvis 2006, p. 171

- Evans, Stuart 2008

- Brooker & Thacker 2010, pp. 71–72

- Laurel Brake, Brooker & Thacker 2010, pp. 84–85

Bibliography

- Horne, Herbert; Mackmurdo, Arthur (1884), The Century Guild Hobby Horse Volume 1, Chiswick Press Century Guild Hobby Horse. vols. 1–7, hathitrust.org

- Meggs, Phillip B; Purvis, Alston W (2006), Megg's History of Graphic Design, John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Codell, Julie F. (1983), "The Century Guild Hobby Horse", 1884-1894, Victorian Periodicals Review

- Sloan, John (2003), Authors in Context- Oscar Wilde, Oxford University Press.

- Evans, Stuart (2008), Century Guild of Artists, Oxford University Press.

- Brooker, Peter; Thacker, Andrew (2010), The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume I: Britain and Ireland 1880-1955, Oxford University Press.

- Hosmon, Robert Stahr (1984), "Hobby Horse, The", in Sullivan, Alvin (ed.), British Literary Magazines: The Victorian and Edwardian Age, 1837-1913, Greenwood Press, pp. 163–167, ISBN 0-313-24335-2