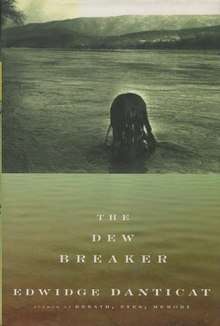

The Dew Breaker

The Dew Breaker is a collection of linked stories by Edwidge Danticat, published in 2004. The title come from Haitian Creole name for a torturer during the regimes of François "Papa Doc" and Jean Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier.[1]

First edition | |

| Author | Edwidge Danticat |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Alfred A. Knopf |

Publication date | 2004 |

| ISBN | 1-4000-3429-9 |

| OCLC | 1014282481 |

The book can read either as a novel or collection of short stories. It is divided in nine portions: The Book of the Dead, Seven, Water Child, The Book of Miracles, Night Talkers, The Bridal Seamstress, Monkey Tails, The Funeral Singer, and The Dew Breaker.

Summary

The Book of the Dead

A Haitian sculptor (Ka) and her father travel from Brooklyn to Florida, to the home of a formerly-jailed and tortured Haitian dissident and his daughter, Gabrielle Fonteneau, a television actress. They are delivering the sculptor's first sale, a statue called “Father”. The sculptor wakes up in a motel room on the morning of the delivery, and discovers her father, also a Haitian refugee, has disappeared with her sculpture.[2]

Seven

A short and seemingly completely unrelated story to the first, Seven is about a man whose wife arrives from Port-au-Prince to NYC. They've been separated for seven years, a number the man despises. He lives in the shared basement of a two-storied house along with two housemates, Michel and Dany. In preparation of his wife coming, he cleans his room as Michel advises, throws some items he knows his wife would hate away, then notifies the landlady of his wife's arrival. The land lady tells the man that if his wife was clean there would be no problem. The man returns to the basement to have a more thorough conversation with Michel and Dany about his wife. The man tells Dany not to mention to his wife any of their nights out or the women the narrator has brought back home. The man changes his phone number and hung pictures that his wife had sent to him upon his bedroom wall. The wife arrives and while going through customs, has her luggage and gifts searched and much is thrown away. All that is left with her is a small, light suitcase. She is finally reunited with her husband.

Her husband works two jobs, a night janitor at Medgar Evers College, and a day janitor at Kings' County Hospital. He leaves his wife to go to the first job. At noon he calls to see what she is doing, and she lies and tells him she's cooking. The wife turns the radio to a Haitian station which talks about the recent death of Patrick Dorismond, a fellow Haitian who was killed by the NYPD. She spends the whole week inside, too afraid to venture out. In her spare time, she writes letters back to Haiti. One to her family and another to a man whom she had an affair with after her husband left for NYC.

When the weekend finally came, the couple walked around Prospect Park until evening. The husband reminisces on the bride and groom carnival theater that they partook in while in Haiti. The two married after a day of knowing each other. At the end of the carnival celebrations, they each burned their clothes and marched on in silence. They yearn for this temporary silence now, instead of the permanent one that has come over them.

Water Child

In this chapter of The Dew Breaker, Danticat[3] touches heavily on themes of voice. Nadine is a Haitian women working as a nurse in the ICU of a hospital in Canasarie. Nadine keeps to herself and tends not to socialize much with the other nurses at the hospital, despite their constant efforts in reaching out. Josette, another Haitian nurse is the only one she somewhat associates with, and not necessarily by choice. The stories underlying tone of sadness reflects in the fact that Nadine is hiding from everyone that she went through with an abortion after being impregnated by a man named Eric. Eric is mentioned in Seven as one of the male roommates. This abortion plays a large role throughout the story, tying back to one's voice because Nadine has never shared with even her own family that she was pregnant. Her parents who still reside in Haiti write to her once a month and constantly try reaching out to talk to their daughter as well as thank her for the money she sends to help with her father's medical expenses. Not only is she caring for her family in Haiti, she is constantly caring for the patients in the hospital. Many of which have undergone laryngectomies and are no longer able to speak. This may be why she felt she was unable to bring a child into the world. Supporting a child financially would be difficult with her sending half of each of her paychecks to her parents and with her keeping to herself, she does not have much of a support system.

Nadine takes special interest in a patient named Ms. Hinds, a young women who had suffered from cancer and was left unable to speak. One day, the two have an interesting interaction after Ms. Hinds is held down by multiple nurses due to her thrashing about in an upset manor. Nadine exclaims, “Let me be alone with her,”. After the other nurses file out of the room, she asks Ms. Hinds to explain what is wrong in which she replies with a pen and paper that she is a teacher, asking why they would send her home in the condition she is in. She goes on to tell Nadine that she is like a Basenji a dog that does not bark. This goes back to the theme of voice. Are we really human and living if we are not able to use our voice? Nadine has outlets to express her voice, however, something holds her back from reaching out to those who care about her.

The Book of Miracles

Narrated by Ka's mother Anne, The Book of Miracles chronicles the family's car trip through NYC to get to Christmas-Eve mass. When they arrive at the church, they have a run-in with a lookalike of Haitian criminal Emmanuel Constant. Constant is known for his involvement, and leadership, in a paramilitary group called the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti, or (FRAPH).[4] Anne, is a very faithful woman and struggles with her daughter Ka's flippant demeanor and fears what could happen if her daughter were to formally acknowledge that this man was Constant. The potential presence of Constant coupled with the religious setting brings to light Anne's own guilt and fear of living a lie, both with her relationship with her daughter and as a member of the Haitian community in NYC.

What Anne struggles to keep secret is that Ka's father was a “dew breaker,” known otherwise as the Tonton Macoutes. These men made up a paramilitary group during the 1950s that formed in order to maintain the political administration of François “Papa Doc” Duvailer, and his son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvailer.[5] The Tonton Macoutes were encouraged to use violence as a way to maintain the political power of the Duvalier's. According to an article titled The Tonton Macoutes: The Central Nervous System of Haiti’s Reign of Terror, it states that, “The militia [of the Tonton Macoutes] consisted mostly of illiterate fanatics that were converted into ruthless zombie-like gunmen,” one of these men being Anne's husband.[5] “He hadn’t been a famous “dew breaker,” or torturer, anyway, just one of hundreds who had done their jobs so well that their victims were never able to speak of them again,” referring to Anne’s husband in The Dew Breaker. Now knowing this, we can see why Anne struggles so much in this scene because she thinks about how her daughter looks at Constant and how she might look at her father knowing he was once a man who participated in similar violent acts. All while also struggling with how Ka would view her for maintaining this secret of her fathers past.

It is not only this secret that she is keeping from her daughter, but also the Haitian community within NYC. Due to events like the election of François “Papa Doc” Duvailer and the terror he brought to the Haitian community and economy, many Haitian immigrants came to the US as early as the 1960s to settle into predominant Haitian communities like New York City and Miami.[6] New York City is where Anne and her family reside, and Danticat specifically addresses Nostrand Avenue as the location where Anne and her husband work. Nostrand Avenue is a well-known site in the Haitian community of New York City, it is known for being the site where Haitian immigrants gathered to lead successful economic lives and work in medium size businesses.[6] These suburbs were places that Haitian members of society could go to feel safe and protest the regimes of the Tonton Macoutes and the (FRAPH). So in summation, for Anne to live within this community knowing that she is married to someone who was involved in these crimes exemplifies the feelings of suppressed guilt and isolation that she must feel within her every day life.

Night Talkers

It's quickly established we're talking again about one of the men of the basement, Dany. Dany has traveled back to Haiti to visit his aunt Estina Esteme. He tells his aunt that he recognized his landlord as the man who killed his parents, who is also the father of Ka. Then Claude appears. Claude is also from NY but has been exiled back to Haiti for killing his father in a rage. Dany has traveled so far because he's found the murderer of his parents, only to find that Claude, a young man and patricide, has been accepted into the community he stills feels to be so much a part of him.

The Bridal Seamstress

In Danticat’s The Dew Breaker, the story titled “The Bridal Seamstress” portrays a Journalism intern named Aline Cajuste, and her interview with Beatrice Saint Fort. This interview highlight's Beatrice's retirement from being a bridal seamstress in the United States, after venturing from her home in Haiti. Early on, the reader will see Beatrice completes actions and responsibilities at her own pace. Aline must wait in the semi-bare living room while her interviewee gets changed, and once more while she makes coffee for the two. Aline is assigned to interview Beatrice on her last day of making wedding dresses for brides. The seamstress is very honest and blunt, especially when Aline asks questions regarding personal information. Beatrice decides to take Aline on a walk down her block in order to better understand her, even after some protest. This walk down the block displays a visual insight to her life. All the houses are similar, but Beatrice describes the different residents inside. She describes each house by the person's nationality and occupation. For example, in one house lives a Dominican social worker. Aline and Beatrice stop in front of a house where a former correctional officer lives, Beatrice explains a brief history of knowing him in Haiti. The walk ends and the two women walk back to Beatrice's front porch, where there is a visual of her front steps and a tree with falling ash leaves. Aline pays special attention to the inside of Aline's home as well, looking for clues of personality traits. Her home lacks detail, giving Aline suspicion to Beatrice's history. Inside the interview proceeds, where Aline answers questions about her education and career choice. When she asks Beatrice about her plans after retirement, she reveals her plan to move and the history with the Haitian prison guard. She shows Aline the soles of her feet and explains how the prison guard once asked her to go dancing, and when she declined he arrested her. She explains the term, chouket lawoze, as Dew Breaker, the translation Danticat has settled on. Beatrice continues to explain the punishment, and how the guard continues to follow and live near her in the United States. After learning this information, Aline leaves and investigates the home of the prison guard, because she does not fully believe Beatrice. She finds an untouched home, and Beatrice confirms this because she knows the man may not live there fully. Beatrice reasons he knows where she lives based on the letters she sends out to her brides, letters explaining her whereabouts for purposes of business. From reading the stories before and after “The Bridal Seamstress”, the reader can recognize the prison guard as Ka's father. There is a strong theme of memory throughout the chapter, based on Beatrice's inconsistency with remembering certain things. There is also the idea that Beatrice is longing for care or attention, and her punisher is not a real figure following her. The peaceful moments she has on the porch, and the ash leaves falling, could display an act of defiance she commits sitting outside on the block. Ideals of patriarchy, communication, and knowledge can also be considered.

Monkey Tails

is the most detailed retelling of life on the ground in Haiti during Jean-Claude Duvalier's regime. It recounts the president and his wife on television, the regular radio addresses, and the exile of Baby Doc. This story also gives an idea of familial relations, the broken families living next door to each other, and never openly acknowledging their illegitimate relations. It features a young Michel, one of the men from the basement.

In this Chapter, Michael reveals his childhood life as he ponders over the time during Baby Doc's (Jean Cleaude Duvalier) presidency. The citizens of Haiti then seek revenge on the military after Baby Doc and his wife flee to France. Crowds begin to form and cause havoc and destruction during their search for the militiamen they were seeking to torture and kill. Readers are introduced to Michael's 18-year-old best friend, Romain, who has a military father that the public is looking for. We also learn about the minor labor Michael provided as a child to, Monsieur Christophe, the neighborhood water and bread shop owner who had power, authority, and control. While in the present moment Michael's wife is pregnant with what he believes is a son, he continues to look back into his past and share what ultimately disconnected those close to him in his neighborhood.

John Moody, author of article ‘Haiti Bad Times for Baby Doc’, writes that rumors had reported that Baby Doc had exiled the country. Upon the rise of this knowledge, U.S. President Ronald Reagan and his administration claimed that the Haitian government had failed, and that Baby Doc had to move to France. This led Baby Doc to re-emerge in the streets of Haiti while referring to his strength as a monkey's tail. Jean Duvalier and his wife were well known for their expensive lifestyle during a time of struggle for most of Haiti.

The Funeral Singer

This is the story of three Haitian women trying to make it through a diploma class in America. The story falls backs on their pasts and futures. One of the women Mariselle may have been a victim of Ka's father, as her husband "had painted an unflattering portrait of the president...He was shot leaving the show."

The Dew Breaker

The final chapter begins by telling the story of a famous Baptist preacher who is captured by the Tonton Macoutes and meets a brutal end in the Casernes Dessalines. It is revealed that the preacher's captor and torturer is the Dew Breaker himself, Ka's father. The preacher puts up a fight using a shard of broken wood and permanently scars his captor's face. Ka's father shoots him several times in the chest, killing him, and in confusion and nausea, leaves the barracks to find himself in the street. A young woman, Anne, runs into him as she sprints towards the barracks to find her missing brother, the preacher. She has no idea that the man she runs into is responsible for her brother's death, and decides to take him home and help heal his bleeding face. The progression of their relationship is left slightly ambiguous, but the chapter ends with Anne talking to her daughter on the phone. Anne realizes that her daughter has recently learned about her father's past as part of the Tonton Macoutes. The conversation is left unfinished.

Themes

Themes in The Dew Breaker include the idea of Marasa,[7] meaning to double or twin, and the theme of forgetting and invalidation of traumatic experiences.[8]

Marasa, The Rule of Two

The reoccurring, cyclical events, the parallels between characters, and the symbolic imagery in each of the short stories is emblematic of Danticat's tale of Marasa. Danticat uses the binary of physical and emotional trauma in power imbalances to expose key thematic issues in the Haitian struggles resulting from the Duvalier totalitarian dictatorship. From Bienaimé's (Papa's) behavioral change transitioning from Haiti to the United States in the chapter “The Dew Breaker,” to the generational split between Beatrice Saint Fort and Aline Cajuste in “The Bridal Seamstress,” the rule of two thrives in each chapter and across sections.[9] Duality is especially seen in the character of Ka who exists both as the child of a Tonton Macoute torturer and as the niece of a man who was killed by that same Tonton Macoute member.[7] Inhabiting a liminal position, Ka represents Haiti where the victimizers and victims live together in shared memory. Likewise, the statue carved by Ka representing her “Papa,” Bienaimé, represents the duality between hunter and hunted, good and bad. By symbolically drowning the statue, Bienaimé's actions surface questions of remembrance, forgiveness, and remorse in “The Book of the Dead."[10] By placing the reader in a story of Marasa, Danticat calls attention to the act of the writer as a “witness” to political, structural, and personal struggles, exposing other thematic issues as a consequence.[11]

Forgetting and Invalidation

The inability to validate traumatic experiences of victims through memory is also a crucial theme in The Dew Breaker.[8] The lack of memory especially plays crucial roles in the domestic settings, particularly in the sections “Water Child” and “Seven” that follow the former relationship between two Haitian immigrants, Nadine and Eric. Eric himself exists as a victim of the U.S. immigration process in which he waits for seven years to bring his wife to America. Both Eric's and his wife's senses of isolation are increased since neither of them discuss the seven years apart nor their extramarital affairs. After her relationship with Eric ends with the arrival of his wife, Nadine too is left in isolation. Unwilling to discuss their relationship nor her abortion of their child, she too lives in domestic trauma.[10]

Critical reception

The Dew Breaker has been well-received as a novel of hope and redemption, but behind that hope is a story or trial and torment by customs and a nation which seemed to turn on itself at every opportunity. Danticat tells not only her own story, but the story of her nation and its people. Haiti is a nation that seems to desire to both forget and retain its memories of the past and the pain it carried with it. For example, in "The Book of The Dead" we hear a story of a young woman who admires her father but was unaware of what he did in his time in prison. This trend of the past being revealed in the end is a recurring theme throughout the stories of the novel, and not just from the somewhat secretive titular character, but from the other characters throughout the stories; such as the aforementioned father and daughter, or from a Brooklyn-based Haitian family who thought that a Dew Breaker[12] was with them inside their church on Christmas Eve. Yet even with all of these negatives coming from the past, the characters, the people of this story never seem to let it truly affect their futures they built for themselves and their families. The Dew Breaker is one of Danticat's older works, but the lesson in both moving forward and remembering the past hold true throughout its pages. “She delivers her most beautiful and arresting prose when describing the most brutal atrocities and their emotional aftermath,” says the Washington Post.[13] Danticat has and is able to take the pain of the people and turn it into a force of knowledge to tell people that often behind a tale of hope is often a tale of trial and escape from a pain that haunts its people to this day.

References

- Davis, Bernadette (March 2004). "The Dew Breaker, Edwidge Danticat: BookPage review by Bernadette Davis". BookPage.com. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- Danticat, Edwidge (June 21, 1999). "The Book of the Dead". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- "Edwidge Danticat". Biography. July 9, 2015. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- "Women Recount Gang Rape, Abuse at Hearing Against Haitian Death Squad Leader Emmanuel Constant". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- "The Tonton Macoutes: The Central Nervous System of Haiti's Reign of Terror". Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- Pierre-Louis, François (September 2013). "Haitian immigrants and the Greater Caribbean community of New York City: challenges and opportunities". Memorias: Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe (21): 22–40. ISSN 1794-8886.

- Bellamy, Maria Rice (2012). "More than Hunter or Prey: Duality and Traumatic Memory in Edwidge Danticat's The Dew Breaker". MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the U.S. 37 (1): 177–197. doi:10.1353/mel.2012.0005. JSTOR 41440718.

- Presley-Sanon, Toni (2016). "Wounds Seen and Unseen: The Workings of Trauma in Raoul Peck's "Haitian Corner and Edwidge Danticat's "The Dew Breaker"". Journal of Haitian Studies. 22 (1): 19–45. doi:10.1353/jhs.2016.0022. JSTOR 24894146.

- Danticat, Edwidge (2004). The Dew Breaker. Vintage Contemporaries.

- Pyne-Timothy, Helen (2001). "Language, Theme and Tone in Edwidge Danticat's Work". Journal of Haitian Studies. 7 (2): 128–137. JSTOR 41715105.

- Danticat, Edwidge (September 6, 2018). An Evening with Edwidge Danticat, Lecture. The University of Kansas Lied Center: The Office of First Year Expereince.

- Kakutani, Michiko (March 10, 2004). "Books of The Times; Hiding From a Brutal Past Spent Shattering Lives in Haiti". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- Danquah, Meri Nana-Ama (25 April 2004). "Tortured Past". Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

Further reading

- Bellamy, Maria Rice. “Silence and Speech: Figures of Dislocation and Acculturation in Edwidge Danticat’s The Dew Breaker” The Explicator, 2013, Vol. 71(3), pp. 207–210

- Henton, Jennifer E. “Danticat’s The Dew Breaker, Haiti, and Symbolic Migration.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 2010, Vol.12(2), p. 11

- Collins, Jo. “The ethics and aesthetics of representing trauma: The textual politics of Edwidge Danticat’s The Dew Breaker” Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 2011, Vol. 47, pp. 5–17

- Mills, Alice. “The Dew Breaker Reviewed” Journal of Haitian Studies, 2005, Vol. 11(1), pp. 174–177

- Conwell, Joan. “Papa’s Masks: Roles of the Father in Danticat’s The Dew Breaker” Obsidian III, 2006, Vol. 6(2), Vol. 7(1), pp. 221–239

- Chen, Wilson C. “Narrating Diaspora in Edwidge Danticat’s Short-Story Cycle The Dew Breaker” Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory, 2014, Vol. 25(3) p. 220-241