The Dead King and his Three Sons

The Dead King and his Three Sons and The King's Sons Shooting at Their Father's Corpse are titles for a story sometimes depicted in medieval and Renaissance art, initially mostly in miniatures in illuminated manuscripts, and later in engravings, paintings and other media.[1]

_-_Solomon_Teaching_Rehoboam%3B_The_Judgment_of_Solomon%3B_Solomon_Testing_the_Legitimacy_of_Three_Brothers_-_Google_Art_Project_(cropped).jpg)

A version is first recorded in the Gemara or commentary part of the Babylonian Talmud, perhaps compiled around 400 AD.[2] Here it has rather different details, and the story may have an unrecorded history before this. In the version known to the Christian Middle Ages, a king wrote in his will that his corpse should be tied to a tree and his three sons told to shoot arrows at it. Whichever hit nearest his heart was to inherit the kingdom. The two elder sons shot arrows, but the youngest refused to do, out of love and respect for his father. The appointed judges of the contest declared him the winner, and so the new king.[3]

This is found in the Gesta Romanorum, a Latin work of the thirteenth century that is a "collection of moralized anecdotes and tales intended as a manual for preachers".[3]

Solomon is the chief judge of the contest in many versions, and regarding the story as an example of the kingly settlement of disputes, led to it being illustrated in some lavish biblical illuminated manuscripts for the French and other courts. There it is often paired with the better-known Judgement of Solomon, which unlike this story actually appears in the Bible.[4]

Source and depiction

In the Talmudic version, a man overhears his wife saying to her daughter "Why are you not careful in your unlawful acts? I have ten sons and only one is from your father". The man's last instructions were that all his property should be left to one son, but he did not say which one. The problem was taken to a rabbi, who advised that each son should go and knock on his father's grave until the father came and explained his intentions. Nine of the sons did so, without response, but the tenth refused. The rabbi judged that he should inherit.[2]

The various Christian versions reduce the number of sons, promote the father in status, usually to that of a ruler, and substitute a much more violent disrespect to the father's remains. The issue of the legitimacy of the sons may or may not be included. In the two earliest versions lances are thrown at the corpse, thereafter bows and arrows are always the weapons. The father is variously described as a strong warrior, a very noble king, a Roman Emperor called Polemius, or a "prince de Saissone".[5] In the various texts, naming the judge as Solomon is unusual, and comes in a version with only two sons. But in artistic depictions, three sons and Solomon as judge was usual in manuscript illustrations.[6]

Manuscripts

The earliest depiction in art may be in three small roundel illustrations in an illuminated psalter of the later 14th century in the Morgan Library & Museum (MS 183), at the page with Psalm 51 (52). The scene is divided between the roundels, and has two sons, bows and arrows, and a royal judge, no doubt intended as Solomon.[7] A depiction carved on a choir stall in Cologne Cathedral was long mis-identified (as the Justice of Trajan); this comes from the first half of the 14th century.[8]

Thereafter the story begins to be commonly depicted in the relatively small group of luxury Bible Historiale manuscripts, lavishly illustrated biblical summaries in French, normally as part of a multi-image group at the beginning of the Book of Proverbs, which in the Middle Ages was believed to have been written by Solomon. Often it forms one of four scenes, the others typically being Solomon Teaching (usually with Rehoboam the pupil), and the Judgement of Solomon (with the baby and two mothers). Often, either of the two judgements, of the disputing mothers or the king's sons, is shown over two images, the first of the participants bringing their dispute before the enthroned Solomon.[9]

Germany

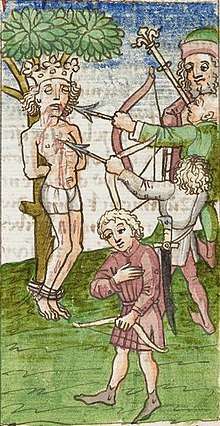

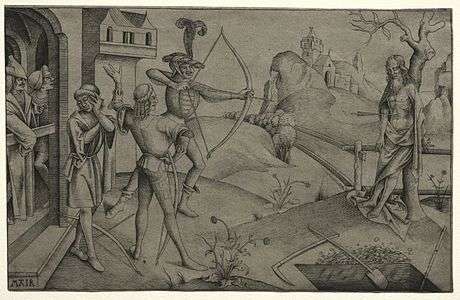

As printed versions in vernacular languages of the Gesta Romanorum began to appear in the late 15th century, the depiction of the scene increased. The first printed edition in German appeared in Augsburg in 1489, after which the number of German images increased.[3] These included engravings by Mair von Landshut and Master MZ (probably Matthäus Zasinger of Munich), both of around 1500, and an anonymous early 16th-century drawing.[10] A drawing by Hans Schäufelein of about 1505 (now Bremen), shows an expansive view of the scene.[11]

Different moments from the shooting scene are shown. In the anonymous drawing the archers are taking aim, in Mair's print one son has shot and the next is about to, while the youngest son looks away in disgust. Wolfgang Stechow, who first set out the history and depiction of the story, describes the print as the "most subtle and moving interpretation of the story in art, despite its many awkward details".[12] It emphasizes the moral interpretation of the story, and Solomon is absent. In Master MZ's depiction the shooting has finished and the youngest son is about to be crowned. In this the commanding turbaned figure on horseback represents Solomon, as the judge of the contest.[13] It is typical of the obscurity of the subject that this print was called a Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian by the great cataloguer Adam Bartsch.[3]

Italy

Italian depictions include a small cassone painting of about 1460 (one of a group of three scenes), a Florentine engraving of 1460–80, and in a painted miniature in a luxury illuminated copy of a printed Bible in Italian.[14] The subject takes the full side of a cassone painted by Francesco Bacchiacca of 1523, now in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, probably the best known of all depictions.[15]

Moralizing interpretations

The story was given a variety of moralizing interpretations, of which one of the most popular was as a warning against blasphemy. The shooting sons may be identified with heretics and Jews, whose attacks on his truth wounded God, as the arrows wounded the corpse. This idea may have been introduced by the Speculum Morale, long wrongly attributed to Vincent of Beauvais.[16]

Renaissance classical make-over

In the mid-16th century the story, depictions of which were rather in decline, was given a classical makeover. Stechow remarks that "It is amusing to see that this was done in a deliberate and avowed literary fake".[17] The Swiss scholar Theodor Zwinger gave a version of the story in his influential Theatrum Humanae Vitae (1565), where he named the father as "Parysadas, king of the Cimmerian Bosphorus" (died 310/309 BC) and also named the sons, explaining that "To prevent this story from remaining anonymous, we have made it more dignified by borrowing the names from Diodorus".[18] Diodorus does indeed recount an inheritance dispute between the sons of this king,[19] but makes it clear it was settled by more conventional means, namely a civil war.[18]

These identifications were followed in literary renditions in various languages, and can be detected in a few 17th-century depictions in art, where "Roman" costume is worn.[18]

See also

- The Frog Princess – a fairy tale involving the king who orders his three sons to shoot arrows

Notes

- Stechow, throughout; Hall, 282

- Stechow, 213

- Shestack, #147

- Stechow, throughout; Hall, 282

- Stechow, 214

- Stechow, 214–215

- Stechow, 215–216 and Figure 5

- Stechow, 215 – his Figure 1

- Stechow, 216–219

- Stechow, 223; Shestack, #147

- Stechow, 219 and Figure 14

- Stechow, 223

- Stechow, 219

- Stechow, 219–220

- Stechow, 219–221

- Stechow, 221–222

- Stechow, 223–224, 224 quoted.

- Stechow, 224

- Book 20, chapters 22–26

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Dead King and his Three Sons. |

- Hall, James, Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- Shestack, Alan, Fifteenth Century Engravings of Northern Europe, 1967, National Gallery of Art (Catalogue), LOC 67-29080 (no page numbers; a biography is followed by numbered entries, here #147)

- Stechow, Wolfgang, "Shooting at Father's Corpse", The Art Bulletin, vol. 24, no. 3, 1942, pp. 213–225. JSTOR