The Cry (book)

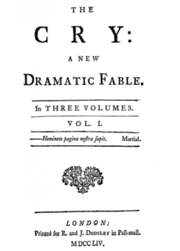

Jane Collier's and Sarah Fielding's The Cry: A New Dramatic Fable (1754) was Fielding's sixth and Collier's second and final work. The work is an allegorical and satirical novel. Collier and Fielding had worked together previously when Fielding wrote The Governess and when Collier wrote An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting, but The Cry is the only work that can be positively ascribed to the two together.[1] Collier died the year after its publication.

The novel was originally produced in three volumes and divided into five parts. The work involves many stories told through the character Portia to an audience consisting of Una, an allegorical figure representing truth, and the "Cry," a chorus that responds in turn.

Background

It is likely that by 1751, Fielding and Collier were living together.[2] In 1753, Fielding published The Adventures of David Simple. Volume the Last, and Collier published An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting. Their joint effort The Cry was published in March 1754. After Collier died in 1755, Richardson encouraged Fielding to revise the work and print a second edition.[3] Originally, Collier planned "A book called The Laugh on the same plan as The Cry", but was never able to complete it before she died.[4]

After working on The Cry, Fielding began to focus on the lives of women and the conditions that they live, which later influenced her work within the Bath community.[5] The community was a group of female writers that challenged the traditional ideas of female education and the role of women in society.[6]

The Cry

The Cry features stories by characters with responses by a group known as "the Cry". They operate as a sort of chorus in the novel.

Part the First

A meeting is held among Portia, Una, and the Cry, who regard Portia as a "dupe." Portia describes Nicanor's family—a gloomy father and the twins Ferdinand and Cordelia—and the Cry accuses her of being in love with Ferdinand, which prompts her to discuss various "romantic" subjects. This leads to Portia telling a story of her courtship with Ferdinand, but the Cry accuse her of being too fond of him. Then, the Cry start abusing Portia for her feelings and for later discussing logic.

Una asks Portia to continue talking about logic. This leads to a story being told of John and Betty, two characters whose tale the Cry enjoys because it confirms their prejudice against educated women. It is then revealed that the Cry cannot stand women learning, and they oppose the thought of it. Portia responds by telling a story of three children, a story of Ben Johnson's jealousy of Shakespeare, and an infant and two monkeys. The Cry react badly to these stories and attack Portia for telling them. Una stops the fighting before it gets out of hand by dismissing the meeting.

Part the Second

The narrator provides the back-story of Nicanor's family, specifically how the father's extravagance almost ruined the family.

Part the Third

Portia begins by discussion pagan gods and other matters on religion. Things go smoothly until Portia discusses Love and the Cry attack her for being mad. Then Portia describes Oliver, Ferdinand's brother, and their courtship. She then questions the Cry and attacks them. Portia condemns Prior Emma and then tells a story about Perdita, which provokes the Cry to claim their admiration for Indian women who kill themselves after their husbands die. They start to attack the Ephesian matron and Portia defends her, which leads her to attacking hypocrites in general and a discussion about the characters of Nero, Xerxes and Alexander the Great. She then describes Oliver's abandoning of Portia for Melantha, and Melantha's loving both Oliver and Ferdinand.

The Cry attack Portia by accusing her of vanity, which prompts Portia to discuss the notion of "knowing one's self" and ignorance. This leads into a story of a merchant and three daughters to explain what she means. The Cry continue to attack Portia and claim that she was jealous of Melantha, but Portia attacks them for hypocrisy. Portia then looks to herself to determine her own bias and then pretends to be Melantha to tell her story. This only encourages accusations by the Cry that Portia is abusing human nature. Portia appeals to Una before she continues to tell the story of Ferdinand and about the obedience of wives. During this time, the men pay attention but the women fall asleep. The discussion abruptly ends when the assembly is dismissed.

Part the Fourth

A woman named Cylinda, introduced in Part the Second as Nicanor's lover, describes her education and her love for her cousin Phaon. She describes how after he is sent abroad, she is unable to marry another and her response to his eventual death. Cylinda continues to talk about her education until Portia speaks up about ridicule and Socrates's death. Portia then proceeds to tell a story about Socrates until Cylinda takes over and describes her refusal to marry. She finishes by discussing her understanding of Greek literature and the writings of Plato.

Cylinda then describes a fever, which is later cured. After the fever, she met with Millamour and became an Epicurean with him. He offers to marry her and she refuses, causing them to separate forever. This leads into Cylinda's account of her time in London and her eventual dissatisfaction with the city. However, she meets up with Nicanor during this time and lives with him. When she believes that he may have deserted her, she leaves to Yorkshire with Artemisia and is proposed to by Artemisia's nephew, Eugenio; she quickly refuses. Soon, she meets Brunetta and her nephew, Eustace. Eustace gives Cylinda news that her fortune, which was previously thought loss, was recovered. Cylinda soon becomes attached to Eustace, who is married, and the two begin to live together. However, he later leaves Cylinda and returns to his wife, which causes Cylinda great distress.

Part the Fifth

Portia returns to telling her story and describes how Ferdinand leaves England. Oliver soon becomes sick, but Melantha is able to nurse him back to health. Portia then describes intrigue between the two brothers and the Cry begin to become excited. Portia then tells of Ferdinand returning and proposing marriage to Portia, which she refuses. The Cry are upset at this point and ask Una to stop the story, but Una intervenes and asks Portia to finish. Portia finishes her story by describing how she left to live in the countryside and how Ferdinand followed after her; Ferdinand's actions forced Portia to depart quickly to Dover and caused her to become ill. Afterwards, she allows Ferdinand to visit her once more, and the two tell each other their stories. The meeting is then broken up for a final time.

Critical response

Jane Spencer described the character Portia as a common image in Fielding's works of an intellectual woman "who suffers from male prejudice against women of learning" and that "she can be seen as a surrogate for her author".[7]

Originally, critics thought that Sarah Fielding wrote the work herself, based on the republication and revision of the work.[8] However, with recent discovery of Collier's notes and other documents, it is certain that Collier and Fielding together wrote the work.[9]

Notes

- Woodward, "Jane Collier, Sarah Fielding ...,” 259–60.

- Woodward, "Jane Collier, Sarah Fielding ...," p. 263

- Sabor p. 151

- Craik, p. xv

- Rizzo p. 38

- Rizzo p. 307

- Spencer p. 218

- Woodward "Who Wrote ..." p. 91-97

- Londry p. 13-14

References

- Battestin, Martin and Battestin, Ruthe. Henry Fielding: A Life. London: Routledge, 1989.

- Craik, Katherine. Introduction to Jane Collier, An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting. Oxford and New York: Oxford World's Classics, 2006. xi–xxxvii.

- Londry, Michael. "Our Dear Miss Jenny Collier", TLS (5 March 2004), 13–14.

- Rizzo, Betty. Companions Without Vows: Relationships Among Eighteenth-Century British Women. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1994. 439 pp.

- Sabor, Peter (2004), "Richardson, Henry Fielding, and Sarah Fielding", in Keymer, Thomas; Mee, Jon (eds.), The Cambridge companion to English literature from 1740 to 1830, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 139–156, ISBN 978-0-521-00757-3

- Spencer, Jane (1998), "Women writers and the eighteenth-century novel", in Richetti, John (ed.), The Cambridge companion to Eighteenth Century Novel, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 212–235, ISBN 978-0-521-42945-0

- Woodward, Carolyn. "Who Wrote The Cry?: A Fable for Our Times", Eighteenth-Century Fiction, Vol. 9, No. 1(1996), 91–97.

- Woodward, Carolyn. "Jane Collier, Sarah Fielding, and the Motif of Tormenting.” The Age of Johnson 16 (2005): 259–73.