The Conquered Banner

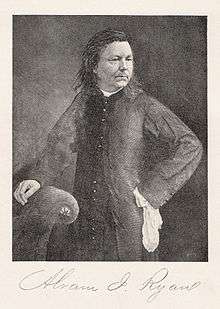

"The Conquered Banner" was one of the most popular of the post-Civil War Confederate poems. It was written by Roman Catholic priest and Confederate Army chaplain, Father Abram Joseph Ryan, who is sometimes called the "poet laureate of the postwar south" and "poet-priest of the Confederacy".[1][2]

Background

The poem was first published on June 24, 1865, in the pro-Confederate Roman Catholic newspaper the New York Freeman under the pen-name "Moina".[1][3] It made Father Ryan famous[4] and became one of the best known poems of the post-war South, memorized and recited by generations of Southern schoolchildren.[5]

Ryan told an interviewer that he wrote the Conquered Banner in Knoxville, Tennessee shortly after General Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox, "When my mind was engrossed with the thought of our dead soldiers and our dead Cause".[4]

David O'Connell has described Conquered Banner as echoing Ralph Waldo Emerson's extremely popular "Concord Hymn". According to O'Connell, readers would have unconsciously have thought of Emerson's poem about "Concord" when Ryan used the word "conquered", and by echoing Emerson's reference to a furled flag, Ryan would have enhanced the patriotic resonance his poem had among Southern readers brought up reciting Emerson's "Concord Hymn".[4] The final verse reads:

Furl that banner, softly, slowly!

Treat it gently—it is holy--

For it droops above the dead.

Touch it not—unfold it never,

Let it droop there, furled forever,

For its people's hopes are dead!

—The Conquered Banner.[6]

This is taken to be Ryan's statement that however noble he and others thought the Confederate cause had been, the defeat was final, and the Confederate idea should be put away forever, along with the Confederate flag.[7]

The poem was published in the first issue of the Confederate Veteran in 1893.[8] John McGreevy called it the most popular Confederate poem in the post-Civil War years.[1]

Attorney and Southerner Hannis Taylor wrote of the impact of Father Ryan's poem on readers sympathetic to the Confederacy: "Only those who lived in the South in that day, and passed under the spell of that mighty song, can properly estimate its power as it fell upon the victims of a fallen cause."[9] The poem reached the height of its popularity between 1890 and 1920.[9]

In 1941 Carl Van Doren included the poem in The Patriotic Anthology, writing that to omit Southern "expressions of patriotism" would be to "falsify the record and also impoverish it".[10]

References

- Catholicism and American Freedom,, John McGreevy Norton and Co., New York 2003, p. 112.

- The Irish in the South, 1815-1877 by David T. Gleeson, reviewed by James M. Woods, The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 69, No. 2 (May, 2003), pp. 415-416.

- The southern poems of the war, Emily Virginia Mason, John Murphy & Co., Baltimore, 1889, p. 426.

- Furl that banner: the life of Abram J. Ryan, poet-priest of the South, David O'Connell, Mercer University Press, 2006, p. 60-62.

- For, Though Conquered, They Adore It, by Bertram Wyatt-Brown, reviewed in The Review of Politics, Vol. 68, No. 1 (Winter, 2006), pp. 147-150.

- Abram Joseph Ryan http://www.civilwarpoetry.org/confederate/postwar/csa.html

- The Victorian homefront: American thought and culture, 1860-1880," Louise L. Stevenson, Cornell University Press, 2001, p. 147.

- Evans, Josephine King (Winter 1989). "Nostalgia for a Nickel: The "Confederate Veteran"". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 48 (4): 238–244. JSTOR 42626824.

- Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920, University of Georgia Press, 2009, pp. 60-61.

- "New Editions," Edward Larocque Tinker, Aug. 31, 1941, New York Times.