Teumman

Teumman was a king of the ancient kingdom of Elam, ruling it from 664 to 653 BCE,[1] contemporary with the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (668 - c. 627). In various sources, the name may be found spelled as Te’umman,[1] Teumann, or Te-Umman. For a time, "many scholars, beginning with G.G. Cameron," believed him to have been the Tepti-Huban-Inshushinak mentioned in inscriptions, although this view has since fallen from favor.[1]

| Teumman | |

|---|---|

| |

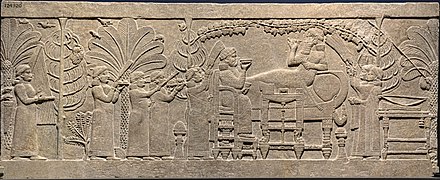

King Teumman wounded at the Battle of Ulai. British Museum. | |

| Reign | c. 664 - 653 BCE |

| Predecessor | Urtak |

| Successor | Ummanigash (son of Urtak) Tammaritu (son of Urtak) |

| Dynasty | Humban-Tahrid dynasty ("Neo-Elamite") |

Succession

Teumman succeeded Urtak.[2] The relationship between Urtak and Teumman is a matter of disagreement. On the one hand, D. T. Potts (2015) refers to Teumann as "apparently unrelated to either Urtak or Hubanhaltash II."[1] Likewise, Boederman's Cambridge Ancient History refers to the accession of Teumman as a "dynastic upset."[2] On the other hand, M. Rahim Shayegan claims that "Te'umman seems to have been the brother of two of his royal predecessors (Huban-Haltaš II and Urtak)."[3] In any event, upon the accession of Teumman, Urtak's sons escaped to Assyria, after which Urtak unsuccessfully demanded that Assyria return Urtak's sons to his custody.[2]

Battle of Ulai (653 BCE)

Ashurbanipal launched a devastating attack on Elam in 653.[4] A text, written in 649, among the annals of Ashurbanipal, records Ashurbanipal's justifications for the war and its conclusion. Ashurbanipal's reasons for the war included "Teumman's insolent messages, his boasting, his evil plots, a lunar eclipse that foretold Teumman's downfall, a seizure inflicted on Teumman by the gods as a warning, and Teumman's declaration of war on Asshurbanipal."[5] The text records that Ashurbanipal had Teumman beheaded, and that Teumman was replaced as king by Ummanigash.[5]

Aftermath

See also

References

- D. T. Potts (12 November 2015). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 449. ISBN 978-1-316-58631-0.

- John Boederman (1997). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-521-22717-9.

- M. Rahim Shayegan (15 September 2011). Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia. Cambridge University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-521-76641-8.

- Bill T. Arnold; Brent A. Strawn (15 November 2016). The World around the Old Testament: The People and Places of the Ancient Near East. Baker Publishing Group. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4934-0574-9.

- John Malcolm Russell (1999). The Writing on the Wall: Studies in the Architectural Context of Late Assyrian Palace Inscriptions. Eisenbrauns. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-931464-95-9.

- Watanabe, Chikako E. (2004). "The "Continuous Style" in the Narrative Scheme of Assurbanipal's Reliefs". Iraq. 66: 112. doi:10.2307/4200565. ISSN 0021-0889.

- Maspero, G. (Gaston); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); McClure, M. L. (1903). History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia and Assyria. London : Grolier Society. p. 210.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.