Tenjukoku Shūchō Mandala

The Tenjukoku Shūchō Mandala (天寿国繍帳) is a Japanese work of textile art. It is the oldest known example of embroidery in Japan, dating back to 622 CE. It was created in honour of Prince Shōtoku, one of the earliest proponents of Japanese Buddhism.[1]

| Tenjukoku Shūchō Mandala | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Unknown ladies-in waiting |

| Year | 622 |

| Medium | Silk thread on gauze and twill |

| Subject | Tenjukoku 天寿国, "The Land of Infinite Life" |

| Dimensions | 89 cm × 83 cm (35 in × 33 in) |

| Designation | National Treasure of Japan |

| Location | Nara National Museum, Nara |

Creation

In the Jōgū Shōtoku Hōō Teisetsu, it is recorded that Tachibana no Ōiratsume, one of the widows of Prince Shōtoku, commissioned the mandala after her husband's death, to represent the heavenly realm to which he had departed so that she could envision his afterlife.[2] The artwork was created by maidservants of the Imperial Court, with the permission of the Empress Suiko.[3] The original was stitched in silk on a series of large square curtains, approximately 5 metres (16 ft) across,[4] but only a small portion of this, measuring approximately 89 centimetres (35 in) by 83 centimetres (33 in), still survives.[3][5][6]

Replica and current version

The mandala is held at the Nara National Museum, but remains the property of the Chūgū-ji temple in Nara Prefecture.[5] The extant version was created in the Edo period by combining remnants of the original embroidery with a replica made in the late 13th century.[3]

Its association with the temple and its reconstruction are due to the work of the Buddhist nun Shinnyo, who recovered the original mandala from its storage at Hōryū-ji in 1273. According to the narratives of Shinnyo's life, she had a dream in which she learned that the mandala contained the death date of the Princess Anahobe no Hashihito (穴穂部間人皇女, Anahobe no Hashihito no Himemiko), consort of Emperor Jomei and mother of Shōtoku (Shinnyo was researching Hashihito, the patroness of Chūgū-ji, as part of her work to restore the temple). The mandala was locked away at Hōryū-ji, but a break-in at the Hōryū-ji treasury allowed Shinnyo to access their stores under the pretext of checking for damages. There, she found the mandala, severely damaged, and was given permission to remove it to Chūgū-ji. She subsequently took it on a fund-raising tour to Kyoto, and received enough donations to fund the creation of a replica.[4]

Both the replica and the original were damaged by fires at Chūgū-ji in the early fourteenth century, but the damaged pieces were preserved and in the nineteenth century were combined together to create the current version.[7] The colour fastness of the original material was superior to that of the later replica; in the extant version of the artwork, the brighter sections are all derived from the original.[3][6]

Content

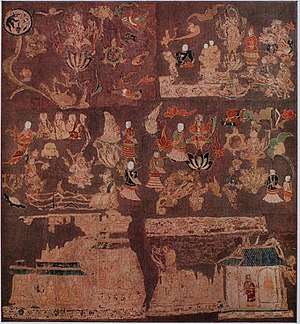

The mandala depicts the Buddhist realm of Tenjukoku (天寿国), or the "Land of Infinite Life", and presents a number of different elements representing various Buddhist concepts. The building in the bottom right is assumed by most scholars to represent the heavenly palace of Zenpōdō from the Maitreya Sutra. The main pattern of tortoises contains characters spelling the names of Shōtoku, Hashihito and Ōiratsume, arranged as a Buddhist triad,[8] and represents Shōtoku's genealogy; other tortoises contain further characters recorded in the Jōgū Shōtoku Hōō Teisetsu, including the death dates of Shōtoku and his mother, and the story of the mandala's creation.[9] The original version of the work contained 100 such tortoises.[5][3] An inscription, purportedly a statement by Shōtoku, was originally appended: "The world is folly. Only the Buddha is real."[10]

The original base fabric on which the images are embroidered is a woven purple gauze, which may have been imported; the later replica sections are stitched onto purple twill or plain white silk. The embroidery threads of the original are z-twisted (right laid) and are sewn exclusively in backstitch while the replica uses looser s-twisted yarn and a variety of different stitches. The looser twist of the yarn may be one of the reasons that the replica sections are less well-preserved.[7]

Some researchers argue that the similarity of the mandala's iconography to Chinese and Korean funeral monuments, together with the gauze fabric on which it was originally stitched, indicate that it is not in fact a Buddhist artefact. This theory suggests that the artwork does not represent Tenjukoku, but rather constitutes a record of the memorial rites performed for Shōtoku, and that the association with Buddhism was a later development.[9][11][12]

References

- Deborah A. Deacon; Paula E. Calvin (18 June 2014). War Imagery in Women's Textiles: An International Study of Weaving, Knitting, Sewing, Quilting, Rug Making and Other Fabric Arts. McFarland. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7864-7466-0.

- 尼門跡寺院の世界: 皇女たちの信仰と御所文化. 産経新聞社. 2009. p. 49.

- "The Tenjukoku Shucho Mandara and the Statue of Prince Shotoku". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Meeks, Lori R. (2007). "In Her Likeness: Female Divinity and Leadership at Medieval Chūgūji". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 34 (2): 351–392. JSTOR 30233816.

- Phyllis Granoff; Koichi Shinohara (1 October 2010). Images in Asian Religions: Text and Contexts. UBC Press. p. 261–. ISBN 978-0-7748-5980-6.

- Kidder, J. Edward Jr (1989). "The Fujinoki Sarcophagus". Monumenta Nipponica. 44 (4): 415–460. doi:10.2307/2384537. JSTOR 2384537.

- Pradel, Maria del Rosario. "The Tenjukoku Shucho and the Asuka Period Funerary Practices". Textile Society of America. University of Nebraska. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- Mita, Kakuyuki. "On the Original Form of the Tenjukoku-shûchô and its Subject" (PDF). Bijutsushi. Japan Art History Society. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- Kenneth Doo Young Lee (1 February 2012). Prince and the Monk, The: Shotoku Worship in Shinran's Buddhism. SUNY Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7914-8046-5.

- "Tenjukoku Shucho". Lieden Textile Research Centre. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- Pradel, Chari (2016). Fabricating the Tenjukoku Shūchō Mandara and Prince Shōtoku’s Afterlives. BRILL. ISBN 9789004182608. Archived from the original on 2017-05-18. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- Pradel, Maria del Rosario. "The fragments of the Tenjukoku shūchō mandara : reconstruction of the iconography and the historical contexts". HKUL. University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 22 May 2017.