Tengenenge

Tengenenge is a community of artists and their families located in the Guruve District of Zimbabwe. It has achieved international recognition because of the large number of sculptors who have lived and worked there since 1966. These include Fanizani Akuda, Bernard Matemera, Sylvester Mubayi, Henry Munyaradzi and Bernard Takawira.[2]

Tengenenge | |

|---|---|

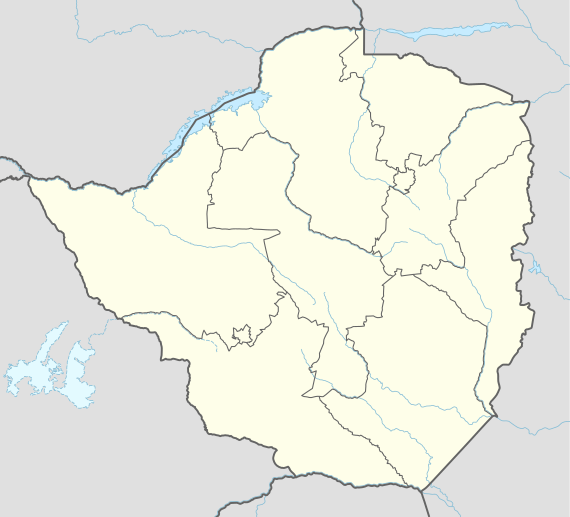

Tengenenge Tengenenge in Zimbabwe | |

| Coordinates: 16°43′51″S 30°56′39″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Mashonaland Central |

| District | Guruve |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2017)[1] | 450 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Website | www |

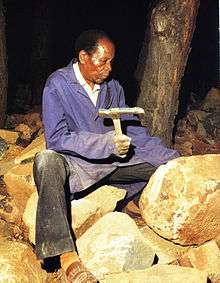

Establishment of the sculpture community

The Tengenenge Sculpture Community was established by Tom Blomefield in 1966. He owned what had originally been a tobacco farm and chromium mine but found that it was by then uneconomic owing to the international sanctions against Rhodesia's white government led by Ian Smith, who had declared Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965. Blomefield wrote that he sought an alternative source of income for his workforce, which materialized when the sculptor Crispen Chakanyuka visited and pointed out that the farm contained an outcrop of hard serpentine stone (part of the Great Dyke) which Blomfield obtained the rights to mine to use for sculpture. Appropriately, Tengenenge means “The Beginning of the Beginning” in the local Korekore dialect of the Shona language.[3] The works from the "first generation" of sculptors at Tengenenge joined those which had been created by others who worked at the National Gallery of Rhodesia in Salisbury, where the then director, Frank McEwen organized exhibitions both nationally and internationally. This created a group of artists whose output was sought after by collectors and which made the names of many, including Fanizani Akuda, Amali Malola, Bernard Matemera, Leman Moses, Sylvester Mubayi, Henry Munyaradzi and Bernard Takawira who had spent time at Tengenenge.[2][4] McEwen and Blomefield diverged in their opinion about how the growing local sculpture movement should evolve. Blomefield encouraged many individual artists from a number of countries including Angola, Malawi and Mozambique to join the local community of mainly Shona ethnicity and was unconcerned whether they had formal training. McEwen had a narrower vision and set up a workshop school at the National Gallery to train those he favoured. Tensions between the two grew until McEwen was deported from Rhodesia by the white minority government in 1973, ironically for "daring to empower blacks".[5]

Later developments

In 1973, Blomefield sold his farm and moved to Harare, although the community at Tengenenge continued to produce sculptures. By 1979 the countryside there was occupied by those fighting for independence in the guerilla war and most of the artists had gone. In December 1979 the Lancaster House Agreement was signed allowing the country to achieve internationally recognised independence in 1980. The artists' community slowly re-formed especially after Blomefield returned in 1985, which encouraged others to do the same. In 1989, the accessibility for visitors to Tengenenge improved with the opening of a tar road and in that year a number of international exhibitions of the sculptors' work were organised, including one in Europe: Beelden op de Berg in Wageningen, the Netherlands.[2] In 1998, a video about Tengenenge was produced which led a reviewer to comment[6] that

"Tengenenge's strongest feature is the honesty with which it faces the controversial issue of the quality of the work made at the site. This point of contention is by no means limited to that community, but it is particularly extreme because of the large number of people who work there."

By 2000, up to 300 artists had lived at Tengenenge at various times but some visitors were critical of the insanitary conditions and lack of education for workers' children.[5] Others, including Celia Winter-Irving, who had spent several months living at Tengenenge and wrote extensively about the sculpture and the artists was much more supportive, believing[2] that

"[Blomefield]'s mentorship had little sense of the paternalism of white supremacy....nor has he imposed his European way of life and its values upon the artists."

Blomefield continued in his role as director of Tengenenge until 2007, when he was succeeded by Dominic Benhura who is also a well-known sculptor.[7] In 2011, a management team of five artists was formed.[8] Other artists who have worked at Tengenenge include Square Chikwanda, Sanwell Chirume, Edward Chiwawa, Barankinya Gosta, Makina Kameya and Jonathan Mhondorohuma.

Current status

Although art sales sustained over 1200 community members at the height of Tengenenge's success, by 2020 Zimbabwe's lengthy economic hardship had taken its toll. The tourist industry had virtually collapsed and new opportunities were scarce.[1][9][10] Tom Blomefield died on April 8th, 2020, aged 95.[11]

See also

References

- Nyavaya, Kennedy (2017-03-05). "How Tengenenge Arts Centre lost its shimmer". The Standard. Harare. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Winter-Irving, Celia (1995). Stone Sculpture in Zimbabwe. Roblaw Publishers. p. 210. ISBN 0908309147.

- Tom Blomefield, in the foreword to the catalogue (1993) for the exhibition "Talking Stones II"; ed. Prichard N, Eton, Berkshire (no ISBN)

- Leyten, H (1994). Tengenenge. Kasteel Groenveld, Baarn, Netherlands. ISBN 9074281052.

- Monda, Tony (2016-03-23). "Truth about Tengenenge: Part Two.…the village Bloemfield wanted to keep in the Dark Ages". The Patriot. Harare. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Zilberg, Jonathan (2001). "Tengenenge". African Arts. 34 (3): 79. doi:10.2307/3337882. JSTOR 3337882.

- "Tengenenge Sculpture Village". ZimFieldGuide. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- "Tengenenge Art Community Management Team". 2013. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- "Tengenenge: Unique craft centre". The Standard. Harare. 2017-10-07. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Larkin, Lance (2014). Following the stone: Zimbabwean sculptors carving a place in 21st century art worlds (pdf) (Thesis). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- Masakadza, Blessing (2020-04-10). "Tengenenge founder dies...Benhura salutes Tom Blomfield". dailynews. Harare. Retrieved 2020-06-30.

Further reading

- Harrie Leyten. Tengenenge, Drukkerij Bakker/M.C. Escher Foundation, 1994, ISBN 90-74281-05-2

- Celia Winter-Irving. Tengenene Art Sculpture and Paintings, World Art Foundation, Eerbeek, The Netherlands, 2001, ISBN 90-806237-2-5

- Celia Winter-Irving. Soottie the cat at Tengenenge, Tengenenge (Pvt) Ltd, Graniteside, Harare, 2001, ISBN 0-7974-2260-9

- Christine Scherer. Working on the Small Difference: Notes on the Making of Sculpture in Tengenenge, Zimbabwe, pp. 180–206 in "African Art and Agency in the Workshop", Indiana University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-253-00749-0

- Tom Blomefield. Stone rich in Africa, Kindle edition, Amazon media, 2016, ASIN B01MYVJXWP