Tel Dan stele

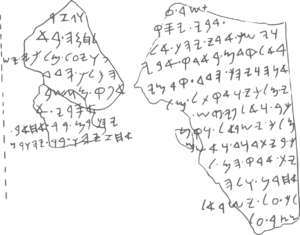

The Tel Dan Stele is a fragmentary stele, discovered in 1993 in Tel-Dan by Gila Cook, a member of an archaeological team lead by Avraham Biran, the pieces having been used to construct an ancient stone wall that survived into modern times.[1] The stele is in several pieces and contains several lines of Aramaic, closely related to Hebrew and historically a common language among Jews. The surviving inscription, which dates to 9th century BCE, details that an individual killed Jehoram, the son of Ahab, king of Israel and the king of the house of David.[2] These writings corroborate passages from the Bible, as the Second Book of Kings mentions that Jehoram, also Joram, is the son of an Israelite king, Ahab, by his Phoenician wife, Jezebel. Applying a Biblical viewpoint to the inscription, the likely candidate for having erected the stele is Hazael, an Aramean king, whose language would have been Aramaic, who is mentioned in Second Book of Kings as having conquered the Land of Israel, though he was unable to take Jerusalem. The stele is currently on display at the Israel Museum,[3] and is known as KAI 310.

| Tel Dan Stele | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Basalt |

| Writing | Old Aramaic (Phoenician alphabet) |

| Created | 870–750 BCE |

| Discovered | 1993–94 |

| Present location | Israel Museum |

Discovery and description

Overview

It consists of several fragments making up part of a triumphal inscription in Aramaic, left most probably by Hazael of Aram-Damascus, an important regional figure in the late 9th century BCE. Hazael (or more accurately, the unnamed king) boasts of his victories over the king of Israel and his apparent ally[4] the king of the "House of David" (bytdwd). It is considered the earliest widely accepted reference to the name David as the founder of a Judahite polity outside of the Hebrew Bible,[5] though the earlier Mesha Stele contains several possible references with varying acceptance. A minority of scholars have disputed the reference to David, due to the lack of a word divider between byt and dwd, and other translations have been proposed. The Tel Dan stele is one of four known inscriptions made during a roughly 400-year period (1200-800 BCE) containing the name "Israel", the others being the Merneptah Stele, the Mesha Stele, and the Kurkh Monolith.[6][7][8]

The Tel Dan inscription generated considerable debate and a flurry of articles, debating its age, authorship, and authenticity;[9] however, the stele is generally accepted by scholars as genuine and a reference to the House of David.[10][11][12]

Discovery

Fragment A of the stele was discovered in July 1993 by Gila Cook of the team of Avraham Biran studying Tel Dan in the northern part of modern Israel. Fragments B1 and B2 were found in June 1994.[13] The stele was not excavated in its "primary context", but in its "secondary use".[14]

The fragments were published by Biran and his colleague Joseph Naveh in 1993 and 1995.[13]

Text

The following is the transcription using Hebrew letters provided by Biran and Naveh. Dots separate words (as in the original), empty square brackets indicate damaged/missing text, and text inside square brackets is reconstructed by Biran and Naveh:

1. [ א]מר.ע[ ]וגזר[ ]

2. [ ---].אבי.יסק[.עלוה.בה]תלחמה.בא[ ]

3. וישכב.אבי.יהך.אל[.אבהו]ה.ויעל.מלכי[ יש]

4. ראל.קדם.בארק.אבי[.ו]המלך.הדד[.]א[יתי]

5. אנה.ויהך.הדד.קדמי[.ו]אפק.מן.שבע[ת---]

6. י.מלכי.ואקתל.מל[כן.שב]ען.אסרי.א[לפי.ר]

7. כב.ואלפי.פרש.[קתלת.אית.יהו]רם.בר.[אחאב.]

8. מלך.ישראל.וקתל[ת.אית.אחז]יהו.בר[.יהורם.מל]

9. ך.ביתדוד.ואשם.[אית.קרית.הם.חרבת.ואהפך.א]

10. ית.ארק.הם.ל[ישמן ]

11. אחרן.ולה[... ויהוא.מ]

12. לך.על.יש[ראל... ואשם.]

13. מצר.ע[ל. ]

Romanized:

1. [ ‘]mr.’[ ]wgzr[ ]

2. [ ---].‘by.ysq[.’lwh.bh]tlḥmh.b‘[ ]

3. wyškb.‘by.yhk.‘l[.‘bhw]h.wy’l.mlky[ yš]

4. r‘l.qdm.b‘rq.‘by[.w]hmlk.hdd[.]‘[yty]

5. ‘nh.wyhk.hdd.qdmy[.w]‘pq.mn.šb’[t---]

6. y.mlky.w‘qtl.ml[kn.šb]’n.‘sry.‘[lpy.r]

7. kb.w‘lpy.prš.[qtlt.‘yt.yhw]rm.br.[‘ḥ‘b.]

8. mlk.yšr‘l.wqtl[t.‘yt.‘ḥz]yhw.br[.yhwrm.ml]

9. k.bytdwd.w‘šm.[‘yt.qryt.hm.ḥrbt.w‘hpk.‘]

10. yt.‘rq.hm.l[yšmn ]

11. ‘ḥrn.wlh[... wyhw‘.m]

12. lk.’l.yš[r‘l... w‘šm.]

13. mṣr.’[l. ]

Translated in English:

1. [ ]...[...] and cut [...]

2. [...] my father went up [against him when h]e fought at [...]

3. and my father lay down, he went to his [ancestors (viz. became sick and died)]. And the king of I[s-]

4. rael entered previously in my father's land, [and] Hadad made me king,

5. And Hadad went in front of me, [and] I departed from the seven [...-]

6. s of my kingdom, and I slew [seve]nty kin[gs], who harnessed th[ousands of cha-]

7. riots and thousands of horsemen (or: horses). [I killed Jeho]ram son [of Ahab]

8. king of Israel, and [I] killed [Ahaz]iahu son of [Jehoram kin-]

9. g of the House of David, and I set [their towns into ruins and turned ]

10. their land into [desolation ]

11. other [... and Jehu ru-]

12. led over Is[rael and I laid]

13. siege upon [ ][15]

Content

In the second half of the 9th century BCE (the most widely accepted date for the stele), the kingdom of Aram, under its ruler Hazael, was a major power in the Levant. Dan, just 70 miles from Hazael's capital of Damascus, would almost certainly have come under its sway. This is borne out by the archaeological evidence: Israelite remains do not appear until the 8th century BCE, and it appears that Dan was already in the orbit of Damascus even before Hazael became king in c. 843 BCE.[16]

The author of the inscription mentions conflict with the kings of Israel and the 'House of David'. The names of the two enemy kings are only partially legible. Biran and Naveh reconstructed them as Joram, son of Ahab, King of Israel, and Ahaziah, son of Joram of the House of David. Scholars seem to be evenly divided on these identifications.[17] It is dependent on a particular arrangement of the fragments, and not all scholars agree on this.

In the reconstructed text, the author tells how Israel had invaded his country in his father's day, and how the god Hadad then made him king and marched with him against Israel. The author then reports that he defeated seventy kings with thousands of chariots and horses. In the very last line there is a suggestion of a siege, possibly of Samaria, the capital of the kings of Israel.[17] This reading is, however, disputed.[18]

Interpretation and disputes

Configuration

The stele was found in three fragments, called A, B1 and B2. There is widespread agreement that all three belong to the same inscription, and that B1 and B2 belong together. There is less agreement over the fit between A and the combined B1/B2: Biran and Naveh placed B1/B2 to the left of A (the photograph at the top of this article). A few scholars have disputed this, William Schniedewind proposing some minor adjustments to the same fit, Gershon Galil placing B above A rather than beside it, and George Athas fitting it well below.[19]

Dating

Archeologists and epigraphers put the earliest possible date at about 870 BCE, whilst the latest possible date is "less clear", although according to Lawrence J. Mykytiuk it could "hardly have been much later than 750".[20] However, some scholars (mainly associated with the Copenhagen school) – Niels Peter Lemche, Thomas L. Thompson, and F. H. Cryer – have proposed still later datings.[21]

Cracks and inscription

Two biblical scholars, Cryer and Lemche, analyzed the cracks and chisel marks around the fragment and also the lettering towards the edges of the fragments. From this they concluded that the text was in fact a modern forgery.[22] Most scholars have ignored or rejected these judgments because the artifacts were recovered during controlled excavations.[10][11][12]

Authorship

The language of the inscription is a dialect of Aramaic.[23] Most scholars identify Hazael of Damascus (c. 842 – 806 BCE) as the author, although his name is not mentioned. Other proposals regarding the author have been made: George Athas argues for Hazael's son Ben-Hadad III, which would date the inscription to around 796 BCE, and J-W Wesselius has argued for Jehu of Israel (reigned c. 845 – 818 BCE).

"House of David"

Since 1993–1994, when the first fragment was discovered and published, the Tel Dan stele has been the object of great interest and debate among epigraphers and biblical scholars along the whole range of views from those who find little of historical value in the biblical version of Israel's ancient past to those who are unconcerned about the biblical version, to those who wish to defend it.

Its significance for the biblical version of Israel's past lies particularly in lines 8 and 9, which mention a "king of Israel" and a "house of David". The latter is generally understood by scholars to refer to the ruling dynasty of Judah. However, although the "king of Israel" is generally accepted, the rendering of the phrase bytdwd as "house of David" has been disputed by some. This dispute is occasioned in part because it appears without a word divider between the two parts.[24] The significance of this fact, if any, is unclear, because others, such as the late Anson F. Rainey, have observed that the presence or absence of word-dividers (for example, sometimes a short vertical line between words, other times a dot between words, as in this inscription) is normally inconsequential for interpretation.[25]

The majority of scholars argue that the author simply thought of "House of David" as a single word – but some have argued that "dwd" (the usual spelling for "David") could be a name for a god ("beloved"), or could be "dōd", meaning "uncle" (a word with a rather wider meaning in ancient times than it has today), or, as George Athas has argued, that the whole phrase might be a name for Jerusalem (so that the author might be claiming to have killed the son of the king of Jerusalem rather than the son of the king from the "house of David".[26][27]

Other possible meanings have been suggested: it may be a place-name, or the name of a god, or an epithet.[24] Mykytiuk observes that "dwd" meaning "kettle" (dūd) or "uncle" (dōd) do not fit the context. He also weighs the interpretive options that the term bytdwd might refer to the name of a god, cultic object, epithet or a place and concludes that these possibilities have no firm basis. Rather, he finds that the preponderance of the evidence points to the ancient Aramaic and Assyrian word-patterns for geopolitical terms. According to the pattern used, the phrase "House of David" refers to a Davidic dynasty or to the land ruled by a Davidic dynasty.[28] As an alternative, Francesca Stavrakopoulou remains sceptical about the significance and interpretation of the inscription and claims that it does not necessarily support the assumption that the Bible's David was a historical figure since "David" which can also be translated as "beloved" could refer to a mythical ancestor.[24] In Schmidt's view it is indeed likely[29] that the correct translation is "House of David."

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tel Dan stele. |

- Historicity of David

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

References

- "Stone Tablet Offers 1st Physical Evidence of Biblical King David : Archeology: Researchers say 13 lines of Aramaic script confirm the battle for Tel Dan recounted in the Bible, marking a victory by Asa of the House of David". Los Angeles Times. 14 August 1993. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Hovee, Eric (14 January 2009). "Tel Dan Stele". Center for Online Judaic Studies. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- "Samuel and Saidye Bronfman Archaeology Wing". The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- Athas, George (2006). The Tel Dan Inscription: A Reappraisal and a New Introduction. A&C Black. p. 217. ISBN 9780567040435. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Finkelstein, Mazar & Schmidt 2007, p. 14.

- Lemche 1998, pp. 46, 62: “ No other inscription from Palestine, or from Transjordan in the Iron Age, has so far provided any specific reference to Israel... The name of Israel was found in only a very limited number of inscriptions, one from Egypt, another separated by at least 250 years from the first, in Transjordan. A third reference is found in the stele from Tel Dan - if it is genuine, a question not yet settled. The Assyrian and Mesopotamian sources only once mentioned a king of Israel, Ahab, in a spurious rendering of the name.”

- Maeir, Aren M. (2013). "Israel and Judah". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. New York: Blackwell. pp. 3523–27.

The earliest certain mention of the ethnonym Israel occurs in a victory inscription of the Egyptian king MERENPTAH, his well-known "Israel Stela" (ca. 1210 BCE); recently, a possible earlier reference has been identified in a text from the reign of Rameses II (see RAMESES I–XI). Thereafter, no reference to either Judah or Israel appears until the ninth century. The pharaoh Sheshonq I (biblical Shishak; see SHESHONQ I–VI) mentions neither entity by name in the inscription recording his campaign in the southern Levant during the late tenth century. In the ninth century, Israelite kings, and possibly a Judaean king, are mentioned in several sources: the Aramaean stele from Tel Dan, inscriptions of Shalmaneser III of Assyria, and the stela of Mesha of Moab. From the early eighth century onward, the kingdoms of Israel and Judah are both mentioned somewhat regularly in Assyrian and subsequently Babylonian sources, and from this point on there is relatively good agreement between the biblical accounts on the one hand and the archaeological evidence and extra-biblical texts on the other.

- Fleming, Daniel E. (1 January 1998). "Mari and the Possibilities of Biblical Memory". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 92 (1): 41–78. JSTOR 23282083.

The Assyrian royal annals, along with the Mesha and Dan inscriptions, show a thriving northern state called Israël in the mid—9th century, and the continuity of settlement back to the early Iron Age suggests that the establishment of a sedentary identity should be associated with this population, whatever their origin. In the mid—14th century, the Amarna letters mention no Israël, nor any of the biblical tribes, while the Merneptah stele places someone called Israël in hill-country Palestine toward the end of the Late Bronze Age. The language and material culture of emergent Israël show strong local continuity, in contrast to the distinctly foreign character of early Philistine material culture.

- Lemche 1998, p. 41: “The inscription is kept in a kind of “pidgin” Aramaic, sometimes looking more like a kind of mixed language in which Aramaic and Phoenician linguistic elements are jumbled together, in its phraseology nevertheless closely resembling especially the Mesha inscription and the Aramaic Zakkur inscription from Aphis near Aleppo. The narrow links between the Tel Dan inscription and these two inscriptions are of a kind that has persuaded at least one major specialist into believing that the inscription is a forgery. This cannot be left out of consideration in advance, because some of the circumstances surrounding its discovery may speak against its being genuine. Other examples of forgeries of this kind are well known, and clever forgers have cheated even respectable scholars into accepting something that is obviously false.”

- Grabbe, Lester L. (28 April 2007). Ahab Agonistes: The Rise and Fall of the Omri Dynasty. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9780567251718.

The Tel Dan inscription generated a good deal of debate and a flurry of articles when it first appeared, but it is now widely regarded (a) as genuine and (b) as referring to the Davidic dynasty and the Aramaic kingdom of Damascus.

- Cline, Eric H. (28 September 2009). Biblical Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199711628.

Today, after much further discussion in academic journals, it is accepted by most archaeologists that the inscription is not only genuine but that the reference is indeed to the House of David, thus representing the first allusion found anywhere outside the Bible to the biblical David.

- Mykytiuk, Lawrence J. (1 January 2004). Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200-539 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Lit. ISBN 9781589830622.

Some unfounded accusations of forgery have had little or no effect on the scholarly acceptance of this inscription as genuine.

- Brooks 2005, p. 2.

- Aaron Demsky (2007), Reading Northwest Semitic Inscriptions, Near Eastern Archaeology 70/2. Quote: "The first thing to consider when examining an ancient inscription is whether it was discovered in context or not. It is obvious that a document purchased on the antiquities market is suspect. If it was found in an archeological site, one should note whether it was found in its primary context, as with the inscription of King Achish from Ekron, or in secondary use, as with the Tel Dan inscription. Of course texts that were found in an archaeological site, but not in a secure archaeological context present certain problems of exact dating, as with the Gezer Calendar."

- Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh (1995). "The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment". Israel Exploration Journal. 45 (1): 1–18. JSTOR 27926361.

- Athas 2003, pp. 255–257.

- Hagelia 2005, p. 235.

- Athas 2003, pp. 259–308.

- Hagelia 2005, pp. 232–233.

- Mykytiuk 2004, pp. 115, 117fn.52.

-

Compare: Hagelia, Hallvard (2005) [2004]. "Philological Issues in the Tel Dan Inscription". In Edzard, Lutz; Retsö, Jan (eds.). Current Issues in the Analysis of Semitic Grammar and Lexicon. Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, ISSN 0567-4980, volume 56, issue 3. 1. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 233–234. ISBN 9783447052689. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

Except for some extremely late datings, most scholars date the text to the second half of the 9th century. The late datings come mainly from the Copenhagen scholars N. P. Lemche,[...] T. L. Thompson[...] and the late F. H. Cryer.[...] A not so late dating is argued by Athas, [...] dating the inscription to around 796 BC.

- House of David, Lemche, 2004, p. 61.

- Mykytiuk 2004, pp. 115,117fn.52.

- Stavrakopoulou 2004, pp. 86–87.

- Rainey 1994, p. 47.

- Lemche 1998, p. 43.

- Athas 2003, pp. 225–226.

- Mykytiuk 2004, pp. 121–128.

- Schmidt 2006, p. 315.

Sources

| Library resources about Tel Dan Stele |

- Athas, George, “Setting the Record Straight: What Are We Making of the Tel Dan Inscription?” Journal of Semitic Studies 51 (2006): 241–256.

- Athas, George (2003). The Tel Dan Inscription: A Reappraisal and a New Interpretation. Continuum International Publishing Group.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Biran, Avraham; Naveh, Joseph (1993). An Aramaic Stele Fragment from Tel Dan, Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 43, No. 2/3 (1993), pp. 81-98. Israel Exploration Society. JSTOR 27926300.

- Brooks, Simcha Shalom (2005). Saul and the Monarchy: A New Look. Ashgate Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, John J. (2005). The Bible After Babel. Eerdmans.

- Davies, Philip R., “‘House of David’ Built on Sand: The Sins of the Biblical Maximizers.” Biblical Archaeology Review 20/4 (July/August 1994): 54-55.

- Dever, William G. (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Mazar, Amihay; Schmidt, Brian B. (2007). The Quest for the Historical Israel. Society of Biblical Literature.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finkelstein, Israel. "State Formation in Israel and Judah: A Contrast in Context, a Contrast in Trajectory" Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 62, No. 1 (Mar. 1999), pp. 35–52.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2007). Ahab Agonistes. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Hagelia, Hallvard (2005). "Philological Issues in the Tel Dan Inscription". In Edzard, Lutz; Retso, Jan (eds.). Current Issues in the Analysis of Semitic Grammar and Lexicon. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mykytiuk, Lawrence J. (2004). Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200–539 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rainey, Anson F. (November 1994). "The 'House of David' and the House of the Deconstructionists". Biblical Archaeology Review. 20 Issue=6: 47.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmidt, Brian B. (2006). "Neo-Assyrian and Syro-Palestinian Texts I: the Tel Dan Inscription". In Chavalas, Mark William (ed.). The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation. John Wiley & Sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schniedewind, William M. and Bruce Zuckerman, "A Possible Reconstruction of the Name of Hazael's Father in the Tel Dan Inscription," Israel Exploration Journal 51 (2001): 88–91.

- Schniedewind, William M., "Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu's Revolt." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 302 (1996): 75–90.

- Stavrakopoulou, Francesca (2004). King Manasseh and Child Sacrifice. Walter de Gruyter.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Suriano, Matthew J., “The Apology of Hazael: A Literary and Historical Analysis of the Tel Dan Inscription,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 66/3 (2007): 163–76.