Taro Yashima

Taro Yashima (八島 太郎, Yashima Tarō, born Atsushi Iwamatsu (岩松 淳, Iwamatsu Atsushi); September 21, 1908 — June 30, 1994) was a Japanese-American artist and children's book author. He immigrated to the United States in 1939 and assisted the U.S. war effort.[2]

Taro Yashima | |

|---|---|

八島 太郎 | |

| Born | Atsushi Iwamatsu September 21, 1908[1] |

| Died | June 30, 1994 (aged 85) |

| Occupation | Children's book author, artist |

| Spouse(s) | Mitsu Yashima |

| Children | Makoto Iwamatsu, Momo Yashima |

Early life

Iwamatsu was born September 21, 1908, in Nejime, Kimotsuki District, Kagoshima, and raised there on the southern coast of Kyushu. His father was a country doctor who collected oriental art and encouraged art in his son.[3] After studying for three years at the Imperial Art Academy in Tokyo, Iwamatsu was expelled for insubordination and missing a military drill.[4] He then joined a group of progressive artists, sympathetic to the struggles of ordinary workers and opposed to the rise of Japanese militarism. The antimilitarist movement in Japan was highly active at the time within many professional groups and crafts, and artists' posters protesting the Japanese aggression in China were widespread.[4] Following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, however, the Japanese government began heavy handed suppression of domestic dissent including the use of arrests and torture by the Tokkō (Special Higher Police).[4]

Both Iwamatsu and his pregnant wife, Tomoe, were imprisoned and brutalized for their opposition to the militaristic government.[4] In 1939, they left Japan for the United States so Iwamatsu could avoid conscription into the Japanese Army and to study art, leaving behind their son Mako (born 1933).[5][4] After Pearl Harbor, Iwamatsu joined the U.S. Army and went to work as an artist for the United States Office of War Information (OWI) and, later, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). It was then that he first used the pseudonym Taro Yashima, out of fear there would be repercussions for Mako and other family members if the Japanese government knew of his employment.[5] After the war, he and his wife were granted permanent resident status by an act of the U.S. Congress. Soon after they had their second child, Momo, while living in New York City. Iwamatsu was able to return to Japan and collect Mako in 1949.

Career as illustrator

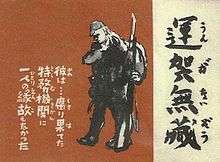

The New Sun, published in 1943 under the name Taro Yashima, was a 310-page autobiographical picture book for adults about life in pre-war statist Shōwa Japan, including details of the harsh and inhumane nature of his imprisonment for his participation in anti-militarist groups in the 1930s.[4]

Its sequel, Horizon is Calling, published in 1947, was in the same format—usually one picture per page, with one or two lines of text. The 276-page book continues the story of his life in Japan under military rule, this time with added Japanese text. In the book, Yashima describes the operations of the Tokkō and the ongoing industrialization of Japan for war in the 1930s.[5][4] During one passage, he mourns the loss of his esteemed teacher "Mr. Isobe", who had been killed in action after being drafted into military service. A kindly teacher of the same name also appears in Yashima's award winning children's book from 1956, Crow Boy. The book concludes with musings about leaving Japan to study art overseas.[6]

Yashima began writing and illustrating children's books early in the 1950s, under the pseudonym he had used in the OSS. His children's book Crow boy won the Children's Book Award in 1955. The picture books Crow Boy (1955), Umbrella (1958), and Seashore Story (1967) were all runners-up for the Caldecott Medal, and they were later designated as Caldecott Honor Books. The annual award by professional librarians recognizes the illustrator of the "most distinguished American picture book for children".[7]

In 1963, on the topic of writing for children, Yashima wrote "Let children enjoy living on this earth, let children be strong enough not to be beaten or twisted by evil on this earth”.[8]

Yashima returned to his home village of Nejime, visiting childhood classmates and familiar scenes that he depicted in several of his children's picture books. He and filmmaker Glenn Johnson produced a 26-minute documentary in 1971, hosted and narrated by Yashima, entitled Taro Yashima's Golden Village.[9]

Published works

- The New Sun (1943)

- Horizon is Calling (1947)

- The Village Tree (1953)

- Plenty to Watch (1954) by Mitsu and Taro Yashima

- Crow Boy (1955)

- Umbrella (1958)

- Momo's Kitten (1961) by Mitsu and Taro Yashima, illustrated by Taro Yashima

- Youngest One (1962)

- Seashore Story (1967)

Personal life

The Yashimas moved from New York to Los Angeles in 1954, where they opened an art institute.[3]

He was the father of renowned actor and voice actor Iwamatsu Makoto and actress Momo Yashima.

He died in Glendale Memorial Hospital in 1994.[2]

References

- "Taro Yashima". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- "Taro Yashima; Artist, Author Aided U.S. in World War II". The Los Angeles Times. July 6, 1994. p. B14. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Taro Yashima Papers". de Grummond Children's Literature Collection. University of Southern Mississippi. July 2001. Retrieved 2013-06-27. With biographical sketch.

- Shibusawa, Naoko (October 2005). ""The Artist Belongs to the People": The Odyssey of Taro Yashima". Journal of Asian American Studies. 8 (3): 257–275. doi:10.1353/jaas.2005.0053. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Pulvers, Roger (September 11, 2011). "Taro Yashima: an unsung beacon for all against 'evil on this Earth'". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- Yashima, Taro (1947). Horizon is Calling. Henry Holt and Company.

-

"Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938–Present".Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). American Library Association (ALA).

"The Randolph Caldecott Medal". ALSC. ALA. Retrieved 2013-06-27. - Laney, Becky. "Taro Yashima: An Author Study". tripod.com. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- "Taro Yashima's golden village". Glenn L. Johnson. 1971.

External links

- Tarō Yashima at Library of Congress Authorities — with 21 catalog records