Taphrina padi

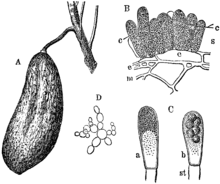

Taphrina padi is a fungal plant pathogen that induces the form of pocket plum gall that occurs on bird cherry (Prunus padus). The gall is a chemically induced distortion of the fruits, which are swollen, hollow, curved and greatly elongated,[1] without a seed or stone, but retaining the style.[2] The twigs on infected plants may also be deformed with small strap-shaped leaves.[1]

| Pocket plum gall | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Taphrinomycetes |

| Order: | Taphrinales |

| Family: | Taphrinaceae |

| Genus: | Taphrina |

| Species: | T. padi |

| Binomial name | |

| Taphrina padi (Jacz.) Mix (1947) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Taphrina pruni var. padi Jacz. (1926) | |

Hosts

Taphrina padi, a 'tongue fungus', produces a distinctive, elongated, tongue-like growth on bird cherry,[3] similar to other closely related species such as Taphrina alni on ader (Alnus glutinosa) and Taphrina pruni on blackthorn (Prunus spinosa).[1] The growth is the distorted fruit and not the fungus itself.[4]

Distribution

The gall is widely distributed, and may be under recorded in the United Kingdom, but it is found throughout the temperate Northern Hemisphere.[5] T. padi has been recorded in India.

Structure and appearance

Fruits

These galls are usually known as 'pocket plums', however alternatives are 'starved plums'; 'bladder bullace; and 'mock plums'. The gall appears on the developing fruit, rendering it inedible and resulting in an elongated, curved, hollow, stone-less gall, usually light green in colour at first; turning brown as the gall develops. In T. padi an identification characteristic is that the style persists at the tip of the gall.

The surface of the gall eventually becomes corrugate and coated with the fungus, showing as a white bloom of ascospore producing hyphae. The totally inedible fruits shrivel and most fall.[6]

Stems

Stems bearing deformed fruit may also thicken and grow with a deformation. The leaves are smaller and strap-like and shoots may be swollen, pale yellow and tinged with red.[1] The fungus may also cause dense clusters of live and dead twig, called "witches' brooms". Some authors suggest these are caused by the very similar Taphrina insititia.[6]

Life cycle

The airborne spores released from the whitish 'bloom' on the fruit are thought to settle in the host's bark and bud scales, growing at first without causing obvious signs, but in the spring the fungus invades the plant tissues, causing swollen and deformed shoots. The fungus remains in these as a mycelium. The gall inducing fungus then grows into the flowers and the developing fruit. The cycle then repeats itself.[6]

The fungus infects the ovaries causing a pseudo-pollination and an enhanced cell division, resulting in the infested fruit being larger than the healthy one.[4]

Infestations of galls

As a fungus, cool and wet weather conditions promote the germination of spores, while warm and dry weather results in infection rarely taking place.[4]

Removing and destroying the galls may help to reduce the infestation. Colonisation can become extensive and eradication very difficult. The disease can to some degree be controlled by carefully removing infected branches, witches' brooms and fruit before the infective air-borne spores are produced.[6]

Applications of copper-containing fungicides have a degree of control over the tongue-fungi.

References

- Notes

- Redfern, Page 249

- Stubbs, Page 43

- Darlington, Page 135

- Nature Gardening. Accessed : 2010-05-26 Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- NBN Gateway Accessed : 2010-05-26

- Royal Horticultural Society. Accessed : 2010-05-26

- Sources

- Cannon, P.F., Hawksworth, D.L., and Sherwood-Pike, M.A. (1985). The British Ascomycotina. An Annotated Checklist. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, Surrey, England, 302 pages.

- Darlington, Arnold (1975). The Pocket Encyclopaedia of Plant Galls in Colour. Poole : Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-0748-8.

- Dennis, R.W.G. (1978). British Ascomycetes. J. Cramer, Vaduz, 585 pages.

- Mix, A.J. (1949). A monograph of the genus Taphrina. Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull. 33: 3-167.

- Redfern, Margaret & Shirley, Peter (2002). British Plant Galls. Identification of galls on plants & fungi. AIDGAP. Shrewsbury : Field Studies Council. ISBN 1-85153-214-5.

- Stubbs, F. B. Edit. (1986). Provisional Keys to British Plant Galls. Pub. Brit Plant Gall Soc. ISBN 0-9511582-0-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taphrina padi. |