Tan Khoen Swie

Tan Khoen Swie (Chinese: 陳坤瑞; pinyin: Chén Kūnruì; 1883/1894–1953) was a Chinese Indonesian publisher who, through the Tan Khoen Swie Publishing Company, published numerous books in Javanese and Malay.

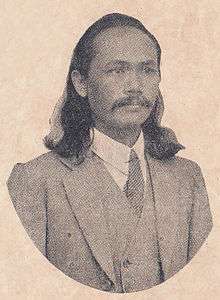

Tan Khoen Swie | |

|---|---|

Tan in c. 1935 | |

| Born | 1883 or 1894 Wonogiri, Residency of Surakarta, Dutch East Indies |

| Died | 1953 |

| Occupation | Publisher |

| Signature | |

| |

Born in Wonogiri, Tan took an early interest in Javanese culture, studying under Mas Ngabehi Mangoenwidjaja of Wonigiri and at the Sunanate of Surakarta. After spending time at a Chinese publishing house in Surakarta, he moved to Kediri and established his own company, publishing at least 279 works, written by a variety of authors and on a wide range of subjects, before his death. Though his son continued the Tan Khoen Swie Publishing Company, it closed soon afterwards.

Early life

Tan was born in Wonogiri, then part of the Residency of Surakarta. Sources disagree as to the year of his birth. The newspaper Kompas and the writers Sam Setyautama and Suma Mihardja give 1883,[1][2] while the sinologist Leo Suryadinata gives 1894.[3] As a child, Tan was interested in Javanese culture, and he would often visit the palace in Surakarta. He also studied locally, under Mas Ngabehi Mangoenwidjaja.[3]

While still in his youth, Tan moved to Surakarta and began working at the Sie Dhien publishing house.[3] He would later marry Lie Gien Nio; the couple had three children.[1] Tan maintained a personal appearance which was commonly remarked upon. Suryadinata likens Tan's long hair and moustache to those of a "modern day hippie",[3] while Ardus M. Sawega of Kompas suggests that this hairstyle was intended as a form of resistance against the Dutch colonial government.[1]

Publishing

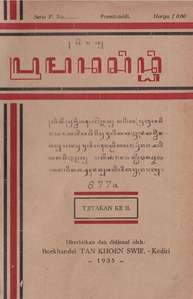

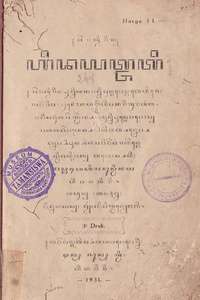

Tan later moved to Kediri, in eastern Java, and established his own company, the Boekhandel Tan Khoen Swie (Tan Khoen Swie Publishing Company).[2] Through his company, Tan published works by a variety of writers, including Ranggawarsita, Mangkunegara IV, Ki Padmosusastro, and Yosodipuro. Authors would often come to Kediri from their hometowns—some from as far away as Cilacap—to meet their publisher. Tan would also publish books under his own name, though in a 2002 interview his great-grandson suggested that he did not write these works, but compiled text from a variety of anonymous sources.[1]

Every year Tan would release a catalogue of his recent publications;[3] Setyautama and Mihardja write that at least 279 books were released through the company. Tan's publications covered a wide variety of subject matter, including wayang, law, theology, philosophy, and agriculture. The works, which were generally not thick, were written in either Javanese or Malay.[1][3]

Tan's publications, which were outside of the colonial-government run Balai Pustaka network, introduced the works of authors to wider audiences than possible in the traditional method of hand-copying manuscripts. Though printed publications in Javanese had been around since the mid-19th century, such works had remained relatively uncommon in Java, and the Javanese language was still undergoing the transition from oral literature to written literature.[1]

- Selected publications

Serat Lambang Praja; Mangoenwidjaja

Serat Lambang Praja; Mangoenwidjaja Serat Pramanasidi; Mangoenwidjaja

Serat Pramanasidi; Mangoenwidjaja Serat Wirid Hidayat Jati; Mangoenwidjaja

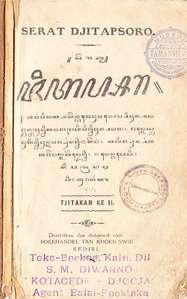

Serat Wirid Hidayat Jati; Mangoenwidjaja Serat Jitaspara; Pujaharja

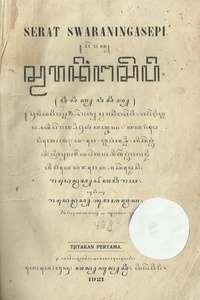

Serat Jitaspara; Pujaharja Serat Swaraningasepi; Partowirya and Sumahatmaka

Serat Swaraningasepi; Partowirya and Sumahatmaka Ngelmi Yatnamaya; Tanaya

Ngelmi Yatnamaya; Tanaya Babad Tuban; anonymous

Babad Tuban; anonymous

Later life and death

Aside from publishing, Tan was active in the vulcanization of Dunlop-brand tyres and owned the Soerabaia mini-market.[1] Among the Chinese community of Kediri, he was involved with the Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan and Hoa Chiao Tsing Nien Hui, and served as a teacher at the Hoe Lie Hiap Hwee school for girls.[2] Tan was also known as a mystic, constructing a cave in his yard for meditation.[3]

Tan died in 1953; though his son Michael Tanzil (Tan Bian Liong) continued the publishing company, it folded soon after. Tan's family continued to live in the house in Kediri, located at 165 Dhoho street, into the 2000s.[1]

Legacy

Sawega wrote that Tan's name remained inexorably linked with the popular literature of early 20th century Indonesia. However, owing to a lack of documentation of his publications, in 2002 the Kediri city government organized a team to research Tan's oeuvre and his life. A spokesman for the team stated that they intended to make Tan's former residence into a tourist attraction.[1]

References

- Sawega 2002.

- Setyautama & Mihardja 2008, p. 363.

- Suryadinata 1995, p. 172.

Works cited

- Sawega, Ardus M (6 April 2002). Peran Kebudayaan Tan Khoen Swie [The Cultural Role of Tan Khoen Swie]. Kompas (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 9 September 2005.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Setyautama, Sam; Mihardja, Suma (2008). Tokoh-tokoh Etnis Tionghoa di Indonesia [Ethnic Chinese Figures in Indonesia] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-9101-25-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Suryadinata, Leo (1995). Prominent Indonesian Chinese: Biographical Sketches. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-3055-03-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links