Talbot effect

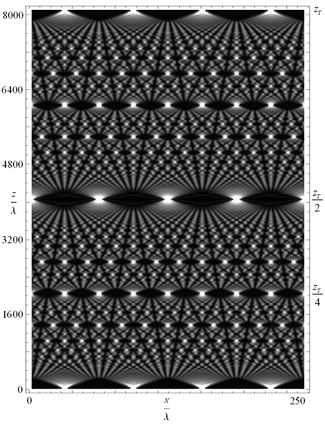

The Talbot effect is a diffraction effect first observed in 1836 by Henry Fox Talbot.[1] When a plane wave is incident upon a periodic diffraction grating, the image of the grating is repeated at regular distances away from the grating plane. The regular distance is called the Talbot length, and the repeated images are called self images or Talbot images. Furthermore, at half the Talbot length, a self-image also occurs, but phase-shifted by half a period (the physical meaning of this is that it is laterally shifted by half the width of the grating period). At smaller regular fractions of the Talbot length, sub-images can also be observed. At one quarter of the Talbot length, the self-image is halved in size, and appears with half the period of the grating (thus twice as many images are seen). At one eighth of the Talbot length, the period and size of the images is halved again, and so forth creating a fractal pattern of sub images with ever-decreasing size, often referred to as a Talbot carpet.[2] Talbot cavities are used for coherent beam combination of laser sets.

Calculation of the Talbot length

Lord Rayleigh showed that the Talbot effect was a natural consequence of Fresnel diffraction and that the Talbot length can be found by the following formula:[3]

where is the period of the diffraction grating and is the wavelength of the light incident on the grating. However, if wavelength is comparable to grating period , this expression may lead to errors in up to 100%.[4] In this case the exact expression derived by Lord Rayleigh should be used:

The atomic Talbot effect

Due to the quantum mechanical wave nature of particles, diffraction effects have also been observed with atoms—effects which are similar to those in the case of light. Chapman et al. carried out an experiment in which a collimated beam of sodium atoms was passed through two diffraction gratings (the second used as a mask) to observe the Talbot effect and measure the Talbot length.[5] The beam had a mean velocity of 1000 m/s corresponding to a de Broglie wavelength of = 0.017 nm. Their experiment was performed with 200 and 300 nm gratings which yielded Talbot lengths of 4.7 and 10.6 mm respectively. This showed that for an atomic beam of constant velocity, by using , the atomic Talbot length can be found in the same manner.

Nonlinear Talbot effect

The nonlinear Talbot effect results from self-imaging of the generated periodic intensity pattern at the output surface of the periodically poled LiTaO3 crystal. Both integer and fractional nonlinear Talbot effects were investigated.[6]

In cubic nonlinear Schrödinger's equation , nonlinear Talbot effect of rogue waves is observed numerically.[7]

See also

References

- H. F. Talbot 1836 "Facts relating to optical science" No. IV, Phil. Mag. 9

- Case, William B.; Tomandl, Mathias; Deachapunya, Sarayut; Arndt, Markus (2009). "Realization of optical carpets in the Talbot and Talbot–Lau configurations". Opt. Express. 17 (23): 20966–20974. Bibcode:2009OExpr..1720966C. doi:10.1364/OE.17.020966. PMID 19997335.

- Lord Rayleigh 1881 "On copying diffraction gratings and on some phenomenon connected therewith" Phil. Mag. 11

- Kim, Myun-Sik; Scharf, Toralf; Menzel, Christoph; Rockstuhl, Carsten; Herzig, Hans Peter (2013). "Phase anomalies in Talbot light carpets of selfimages". Opt. Express. 21 (1): 1287–1300. Bibcode:2013OExpr..21.1287K. doi:10.1364/OE.21.001287. PMID 23389022.

- Chapman, Michael S.; Ekstrom, Christopher R.; Hammond, Troy D.; Schmiedmayer, Jörg; Tannian, Bridget E.; Wehinger, Stefan; Pritchard, David E. (1995). "Near-field imaging of atom diffraction gratings: The atomic Talbot effect". Physical Review A. 51 (1): R14–R17. Bibcode:1995PhRvA..51...14C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.51.R14.

- Zhang, Yong; Wen, Jianming; Zhu, S. N.; Xiao, Min (2010). "Nonlinear Talbot Effect". Physical Review Letters. 104 (18): 183901. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104r3901Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.183901.

- Zhang, Yiqi; Belić, Milivoj R.; Zheng, Huaibin; Chen, Haixia; Li, Changbiao; Song, Jianping; Zhang, Yanpeng (2014). "Nonlinear Talbot effect of rogue waves". Physical Review E. 89 (3): 032902. arXiv:1402.3017. Bibcode:2014PhRvE..89c2902Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.89.032902.