Swiss Private Bankers Association

The Swiss Private Bankers Association is a Swiss trade association made up of banking institutions that meet the legal definition of a private banker according to Swiss law. Based in Geneva, Switzerland, and currently has six members.

| |

| Formation | November 29, 1934 |

|---|---|

| Founders | Max Ernst Bodmer, Albert Pictet, Paul Bugnion, Armand von Ernst von Stürler, Jean Mirabaud, Eduard von Orelli, Eric du Pasquier, Bernhard Sarasin, Theophil Speiser, Walter Wegelin |

| Founded at | Bern |

| Purpose | Represent the interests of Swiss Private Bankers |

| Headquarters | Geneva |

| Coordinates | |

Membership (2016) | 6 |

Secretary General | Jan Langlo |

President | Grégoire Bordier |

| Website | swissprivatebankers |

The Swiss Private Bankers Association was founded in 1934 following the enactment of the Federal Act on Banks and Saving Banks, which recognised the special status of private bankers.[1][2] Its permanent secretariat is based in Geneva. The objective of the Swiss Private Bankers Association, as defined in its articles of association, is to represent the concerns and interests of its members to the Swiss government authorities, among others.

History

The history of private bankers in Switzerland is closely linked to the country's economic development as well as that of its main cities: Basel, Bern, Geneva, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel, St. Gallen and Zurich. Most private bankers began as trading houses, evolving over the years into financial institutions.[3][4]

A nascent industry

In Basel, the Reformation of 1521 brought large numbers of refugees to the city, where they grew prosperous from the silk trade. This development turned Basel into a main centre of banking and finance.[4]

The history of private bankers in Geneva started around 1550, with the influx of Huguenots fleeing persecution in France[3] shortly after the city of Calvin proclaimed itself a Republic. These Protestant refugees were members of the merchant class and were equipped with substantial wealth, commercial and financial know-how, and personal connections in all the main European cities. Present in every international market, over time they built up a unique expertise in bills of exchange, precious metals and credits.[4] 'This created favourable conditions for bankers in Geneva to engage in transactions that were not directly connected to trade, enabling them to further develop their activities beyond their borders'.[5]

Shortly before the French Revolution, Geneva bankers discovered a new area in which 'they would excel from then on':[5] wealth management, which to this day remains a main focus for Swiss private bankers. 'They were often [...] capitalists who invested their own wealth, along with that of their family members or friends'.[6]

Most of the Swiss private banking houses were established around this time, mid-eighteenth century. They were the most influential players in the Swiss banking system.[7] The defining characteristic of their legal structure was the unlimited liability of partners.

The pioneers included :

- In Geneva: Lombard, Odier & Cie (1796), Pictet & Cie (1805), Mirabaud & Cie (1819), Bordier & Cie (1844), Gonet & Cie (1845), Pivot & Cie (renamed Mourgue d’Algue in 1976), and Darier & Cie (1880);

- In Lausanne: Landolt & Cie (1780) and Hentsch Chollet & Cie (1882);

- In Basel: La Roche & Co. (1787), Sarasin & Cie (1841) and E. Gutzwiller & Cie (1886);

- In Bern: Marcuard & Cie (1750);

- In St Gallen: Wegelin & Co (1741);

- In Zurich: Rahn Bodmer Co. (1750).[3][4][5][8]

However, private bankers were unable to meet the increasing need for finance brought about by the rapid development of industry in the second half of the 19th century. It was around this time that their first rivals appeared, in the form of credit banks structured as limited liability companies. In Geneva, during the last quarter of the 19th century, 'competition intensified due to the establishment [...] of the first foreign banks'[5] followed, in the early 20th century, by large Swiss banks.[9]

To bolster their position in relation to competitors of a new kind, private bankers created the first permanent banking syndicates, which can be seen as the ancestors of the Swiss Private Bankers Association: the Quatuor (1840) and the Omnium (1849), followed by Union financière de Genève (1890), which remained active until December 2013 under the name Groupement des Banquiers Privés Genevois.[5]

In Basel, where the sector emerges much later than in Geneva, around the mid-19th century, Private bankers were responsible for founding the Swiss Bank Corporation (which merged with UBS in 1998). Indeed, Basel private bankers created two separate banking syndicates, the Bankverein and the Kleiner Bankverein. The former set up the Basler Bankverein, the ancestor of SBC, in 1872, while the latter founded the Basler Handelsbank, purchased by SBC in 1945.[4][9]

Founding of the Swiss Private Bankers Association

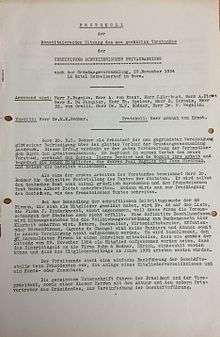

The Swiss Private Bankers Association was founded in Bern, on 29 November 1934, following the adoption of the new Federal Act on Banks and Savings Banks on 8 November 1934. The law recognised the special status of private bankers but also suggested ‘closer collaboration’ amongst them.[2] The aim of the association was to represent ‘the professional interests of private bankers’. Forty-eight banks applied to become members.[1] Its first Chairman was Max Ernst Bodmer.

The golden age of private wealth management

With two World Wars, the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, the first half of the 20th century was a difficult period for private bankers.[7] However, the end of the Second World War allowed private bankers to grow more vigorously than ever before and to position themselves as ‘the recognised specialists in wealth management’.[7] Several factors contributed to their success: the fact that Switzerland had remained outside the conflicts that ravaged the rest of Europe, ‘the country's exceptional political stability’,[10] the acceleration of banking and financial disintermediation in the 1980s and 1990s, the globalisation and deregulation of financial markets, and the liberalisation of capital flows.[11] These developments boosted wealth management.[12][13]

The second half of the 20th century was, somewhat paradoxically, also a time of consolidation for the private banking sector. According to Swiss National Bank statistics, there were 81 private bankers in Switzerland at the end of 1941, but only 17 in 2000.[14] This consolidation took three different forms:

First, several private bankers, such as Ehinger & Co. in Basel or Ferrier Lullin & Cie in Geneva, were acquired by large Swiss banking groups. Second, some private bankers changed their legal structure, becoming listed or unlisted limited liability companies mainly to resolve succession issues or as a way of financing their growth, such as Julius Baer & Cie in 1975, Vontobel in 1984 and Sarasin in 1986.[15] Third, some private bankers simply disappeared, such as the Geneva bank Leclerc & Cie, which closed in 1977, or the St. Gallen-based bank Wegelin & Co., which was forced to sell most of its operations to Raiffeisen Group in 2012 following a tax-evasion dispute opposing the United States authorities to many Swiss banks.[16][17]

Despite this consolidation, a new private bank was established during this period. Reichmuth & Co in Luzern was founded in 1996[18] and joined the Swiss Private Bankers Association in 2003.

Changing legal structures

At the beginning of 2014, the Swiss Private Bankers Association had lost five of its remaining 12 members: to adapt to the requirements international financial centres unfamiliar with the traditional Swiss definition of a private banker,[19][20][21] some private bankers chose to break with ‘more than 200 years of history’ by changing their structure to limited liability companies.[22] This was the case for Landolt & Cie in January 2013[23][24] followed in February 2013 by Pictet & Cie and Lombard Odier & Cie.[22][25][26][27][28] Several months later, Mirabaud & Cie and La Roche & Cie followed suit.[29][30][31] In February 2016, Gonet & Cie abandoned its private banker structure and became a holding company organised as a limited liability company.[32] As a result, these banks no longer met the legal definition of a private banker with unlimited liability for the commitments of the bank.[33] A new organisation, the Association of Swiss Private Banks, was founded on 1 January 2014: its articles of association allow it to admit as members both limited companies and traditional private bankers.[34][35]

The Swiss Private Bankers Association remains active today, with six members.[36]

‘Private Bankers’ collective trademark

In Switzerland, the Federal Law on Banks defines a ‘private banker’ as any bank organised as a sole proprietorship, general partnership, limited partnership or limited stock partnership, in which one or more partner bears unlimited liability for all the commitments entered into by the bank.[37][38] This is one of the main characteristics of private bankers.[39]

The term ‘private bankers’ is often confused with the term ‘private bank’, which refers more broadly to any bank focusing on private wealth management, most of which are structured as a limited company.[4] To prevent improper use of the term ‘private banker’ by people or institutions that do not meet the legal definition, the Swiss Private Bankers Association registered ‘private banker’ and its linguistic variations with the Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property in 1997. The SPBA has had exclusive control of the ‘private banker’ trademark in Switzerland since that time.[40]

Notes and references

- Minutes of the Foundation of the Association, 29 November 1934, SPBA archives

- "Federal Act on Banks and Savings Banks chap I, art. 1". Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Louis H. Mottet, Les grandes heures des banquiers suisses, Delachaux & Niestlé S.A., Neuchâtel-Paris, 1986, pp. 49-50

- Gerhard R. Schäpper, "Le Banquier Privé Suisse et ses Défis à venir", Association des Banquiers Privés Suisses, Geneva, July 1997

- "Six siècles d'activités bancaires à Genève". Journal de Genève. 23 July 1981. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Louis H. Mottet, Les grandes heures des banquiers suisses, Delachaux & Niestlé S.A., Neuchâtel-Paris, 1986, pp.106-107

- Gerhard R. Schäpper, Le Banquier Privé Suisse et ses Défis à venir, Association des Banquiers Privés Suisses, Geneva, July 1997, pp.19-28

- "Le rôle des banquiers privés en Suisse". Gazette de Lausanne. 27 October 1942. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Louis H. Mottet, Les grandes heures des banquiers suisses, Delachaux & Niestlé S.A., Neuchâtel-Paris, 1986, p. 80

- "L'avenir des banques". Journal de Genève. 25 October 1978. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Désintermédiation bancaire et désintermédiation financière sont-elles toujours d'actualité depuis 2008 ?". 21 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Der Schweizer Big Bang als Chance". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 5 December 1995.

- Youssef Cassis, Les capitales du capital, Histoire des places financières internationales, Ed. Slatkine, 2005, p. 304

- Le Banquier Privé Suisse et ses Défis à venir, Association des Banquiers Privés Suisses, Geneva, July 1997, p. 30

- "Banques privées en Suisse, une nouvelle page se tourne". Journal de Genève. 14 November 1986. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Acculée, Wegelin & Co cède ses activités à Raiffeisen". Le Temps. 1 February 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Gerhard R. Schäpper, Le Banquier Privé Suisse et ses Défis à venir, Association des Banquiers Privés Suisses, Geneva, July 1997, pp. 29-31

- "Déjeuner avec Christoph Reichmuth". Le Temps. 26 January 2004.

- "Grandeur et nécessité". Le Temps. 5 February 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Schisme chez les banquiers privés". Le Temps. 5 February 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Le modèle hybride calibré international". L’Agefi. 6 February 2013.

- "Swiss private banks ditch 200 years of history". The Financial Times. 6 February 2013.

- "La banque Landolt & Cie fusionne avec la banque belge Degroof". rts.ch. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Nous voulons rester indépendants dans un monde qui change radicalement". Bilan. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Privatbanquiers: Pictet und Lombard Odier gehen neue Wege". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 6 February 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Genfer Privatbanken werden Kapitalgesellschaften". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 5 February 2013.

- "Pictet, Lombard Odier to Drop Centuries-Old Bank Structure". Bloomberg. 6 February 2013.

- "L'activité et l'esprit seront préservés". L’Agefi. 6 February 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Ende einer langen Tradition". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 13 February 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Unbeschränkt haftenden Teilhaber: Neue Rechtskleider für "echte" Privatbanken". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Grégoire Bordier: 'Je me sens comme le dernier des Mohicans'". Le Temps. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "L'adoption d'une structure plus classique". L’Agefi. 4 February 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "L'Association pourrait redéfinir son activité". L’Agefi. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Die Genfer Privatbanken organisieren sich in einer neuen Vereinigung". Finews. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "L'Association de Banques Privées Suisses prend la relève". Tribune de Genève. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Banquiers privés, les derniers Mohicans". Bilan. 17 February 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Federal Act on Banks and Savings Banks, chap. I, art. 1". Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Les banquiers privés suisses affûtent leurs armes". Journal de Genève. 6 November 1997. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Active investor champions unlimited partnerships". The Financial Times. 6 August 2012.

- "Was ist ein Privatbankier?". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 23 October 1998.