Susse Frères

The French firm Susse Frères manufactured a daguerreotype camera which was one of the first two photographic cameras ever sold to the public. The company was also engaged in the foundry business and owned a large foundry in Paris.

History

Production of daguerreotype camera

On the 19th of August 1839, François Arago publicly unveiled the previously secret details of the daguerreotype process, the first publicly announced photographic process. Two months earlier, on the 22nd of June 1839, its inventor Louis Daguerre had signed contracts with two manufacturers, Alphonse Giroux and Maison Susse Frères, Place de la Bourse 31, Paris,[1] to produce the first commercially available photographic cameras. The two companies were granted exclusive rights to make and sell the special camera obscura designed by Daguerre, as well as the several lesser items of equipment needed to work the process.[2]

The only known surviving Susse Frères daguerreotype camera, made in 1839, is on display in the permanent camera museum of the WestLicht auction house in Vienna, Austria.

According to expert Michael Auer, the camera's lens was made by optician Charles Chevalier and its brass mount is hand-engraved "No3" and "III", indicating that it is only the third lens Chevalier made for a daguerreotype camera. In the 19th century, it was common for makers to serially number their lenses. The glass lens itself is an 81 mm diameter meniscus achromatic doublet, concave surface foremost, and has a focal length of 382 mm. The front of the brass lens barrel features a diaphragm with a fixed 27 mm diameter opening, giving the lens an effective working aperture of slightly over f/14. Attached to the diaphragm is a manually operated pivoting brass shutter, sufficient for its purpose because of the very long exposures required.

The camera, constructed according to Daguerre's specifications, was designed for making 8.5x6.5 inch (216x167 mm) "whole plate" daguerreotypes and optimized for photographing landscapes. No claim was made that either the camera or the daguerreotype process itself, in its then-current state of development, was suitable for portraiture.

The cameras made by the competing manufacturer, Alphonse Giroux et Compagnie, are nearly identical. There are only two obvious differences: their color and their labels. The Giroux cameras were made of hardwood and have a varnished natural wood finish, while the Susse Frères camera was made of a softer wood and painted black. The labels on Giroux cameras are ornate and framed in a brass oval. They declare (in French) that "no apparatus is warranted unless it bears the signature of M[onsieur] Daguerre and the seal of M[onsieur] Giroux". They feature a small red wax seal dated with the year and were actually hand-signed by Daguerre. The Susse Frères camera has a simpler octagonal label claiming only that the camera was made "according to the official plans deposited by M[onsieur] Daguerre at the Ministry of the Interior".

Each lens had to be individually hand-made by expert opticians and machinists and it accounted for most of the price of the camera. The Giroux camera sold for 400 francs, the plainer Susse Frères version cost 350 francs. Neither sum represented a casual purchase or was affordable to the average citizen. In 1839, 350 francs meant a pile of silver coins, or a small stack of gold coins containing a total of over three troy ounces of pure gold, or the more convenient gold-redeemable paper equivalent.

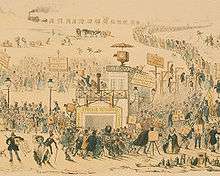

Although Théodore Maurisset's contemporary humorous lithograph La Daguerréotypomanie depicts a throng of customers besieging the Susse Frères establishment and carrying away cameras at a prodigious rate, and although at least fifteen of the cameras made by Giroux still exist, no examples of the Susse Frères version were known until one came to light in 2006. It was found among the effects of Günter Haase, formerly a Professor in the Department of Scientific Photography at the University of Frankfurt. Haase had received it as a gift from a colleague who died in 1963. It was sold at auction in 2007 for a final price of €580,000.

Susse Frères bronze foundry

The Susse Frères firm was also engaged in the foundry business and owned a large foundry in Paris. The company is well known for their fine bronze castings with superbly applied patinas. After the death of Pierre-Jules Mène in 1879, the Susse Frères foundry acquired the rights to reproduce his models and produced posthumous proofs marked "Susse foundeur éditeur, Paris".[3]

References

- Marie-Sophie Corcy: Les substances accélératrices, In: Le Daguerréotype français, Paris 2003, pp. 262-265.

- "Rachel Stuhlman: Luxury, Novelty, Fidelity - Madame Foa's Daguerreian Tale. In: Image, Journal of Photography and Motion Pictures of George Eastman House, Special double issue, 1997 (Vol. 40, No. 1-4.), pp. 2-61. Daguerre's original instruction manual (the first photographic bestseller) states: The public is informed that the apparatus approved by Daguerre, constructed by his instruction and signed by him, is sold by Alphonse Giroux et Cie, rue du Coq-Saint-Honore, and Susse Frères, place de la Bourse. In designating the fashionable emporia of Susse Frères and Alphonse Giroux as the sole agents authorized to sell the first brand-name (as it were) daguerreian outfits, certified by the inventor himself, Daguerre ignored his obligation to the optician Charles Chevalier.

- Kjellberg, Pierre (1994). Bronzes of the 19th Century (First ed.). Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. p. 471. ISBN 0-88740-629-7.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Susse Frères. |