Suseok

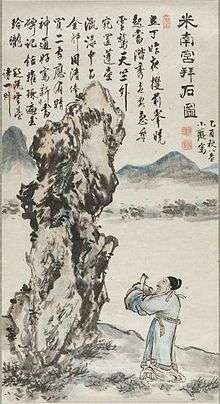

Suseok (수석), also called viewing stones or scholar's stones, is the Korean term for small naturally occurring or shaped rocks which are traditionally valued.[1] Such stones are similar to Chinese gongshi and Japanese suiseki.[2]

| Suseok | |

| Hangul | 수석 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 水石 or 壽石 |

| Revised Romanization | suseok |

| McCune–Reischauer | susŏk |

| IPA | [sʰu.sʰʌ̹k̚] |

Suseok can be any color. They vary widely in size – Suseok can weigh hundreds of kilograms or much less than one kilogram. The term also refers to the stones which are placed in traditional Korean gardens.

History

Suseok began as votive art over 3000 years ago, and began to be seen as worthy of scholars a thousand years ago. The art usually works on three scales: large installations of monumental shaped stones as ornamental gates; medium-sized shaped stones for landscape decoration within Korean gardens; and the smaller shaped stones for scholar's tables, the most important of these scales.

Chinese scholar's rocks influenced the development of suseok in Korea.[2]

Evaluation

Early on, important sites within landscape were marked with shaped stones, similarly to distance markers on post roads. Burial sites were also given permanent marking by large scale tumuli or mounds, often surrounded by anthropomorphic shaped stones much akin to that of Inuit or First Nations' memory markers. The animistic belief of nature being alive, and large-scaled elements of nature having souls, has led to the continued use of massive sculpted stone in natural forms throughout Korean traditional entranceways, as the firstgrowth cedarwood traditionally used for gates is now rare.

As Confucian scholarship ascended into the golden age of the Joseon dynasty, scholar rocks became an essential fixture of the writing tables of the yangban class of scholars, and a brilliant example of Confucian art. Smaller ceramic versions of scholar's rocks have been seen cast in celadon and used as brush-holders, as well as water droppers for scholar's calligraphy – particularly in the shape of small mountains.

In Popular Culture

The gifting of a suseok plays a major symbolic role in Bong Joon Ho's Parasite.[3]

Genres of Korean stone art

- mountain view (horizontal and vertical)

- shaped jade mountains

- shaped rock crystal mountains

- abstract shape

- overhanging shapes

- organic mineral shapes (calcites, pyrites)

- stalactite and stalagmite stelae

- shamanistic shape

- single stone buddhas

- multiple stone buddhas

- astrological year figures (dragon, snake, monkey etc.)

- tree and house shapes

- fossilized fish

- fossilized insects

- enhanced coloured stones

Standard reference work

- Soosuk, #72 in a series of books on Korean culture, Daewonsa Publishing Co, Ltd (Korea, 1989), ISBN 89-369-0072-2 (in Korean)

See also

- Gongshi or Chinese scholar's rocks

- Suiseki

- Korean art

- Korean sculpture

- Korean culture

- List of Korea-related topics

References

- Suseok at KoreanViewingStones.com; retrieved 2013-2-7.

- Brokaw, Charles. (2011). The Temple Mount Code, p. 73.

- ; Bong Joon Ho Reveals the Significance of 'Parasite's' Scholar Stone, Hollywood Reporter, retrieved 2020-3-18.