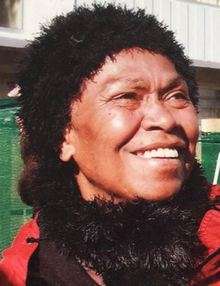

Susanna Ounei

Susanna Ounei (15 August 1945 – 21 June 2016) was a Kanak independence activist and feminist from New Caledonia who spent her last years in New Zealand. She supported various other causes including a nuclear free Pacific and Maori independence.

Susanna Ounei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 August 1945 Ouvéa, Loyalty Islands, New Caledonia, France |

| Died | 21 June 2016 (aged 70) Wellington, New Zealand |

| Nationality | French (New Caledonia) |

| Other names | Susanna Ounei-Small |

| Occupation | Activist |

Early years

Susanna Ounei was born in 1945 in Ouvéa in the Loyalty Islands Province of New Caledonia.[1] Her official birthdate was 15 August 1945, although later in life she found that this date may have been incorrect.[2] She grew up in Poindimié on the east coast of New Caledonia.[1] Under French colonial rule the Kanak population fell from about 70,000 in the pre-colonial era to about 26,000 in the 1980s. The Kanaks were segregated from whites and were subject to many restrictions and impositions. Ounei wrote that "We grew up seeing how our parents were humiliated."[3] Serious Kanak resistance began to develop in the 1960s and 1970s. In response, the French government encouraged massive migration to New Caledonia to reduce the Kanaks to a powerless minority.[3]

As a schoolgirl Ounei resented the racial arrogance of her teachers, and hoped that there would some day be a way to fight such behaviour. She wrote, "My dreams became a reality in September 1969, when Nidoïsh Naisseline, the high chief['s son] of Mare returned to New Caledonia from France and established a political group called the 'Red Scarves'."[4] Ounei joined the Foulards Rouges (Red Scarves), which agitated for Kanak independence from France. She had a job in a bank, and often used her wages to help other members of the group. She also participated in the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP) movement and in the Pacific women's movement.[2]

Feminism

Ounei has pointed out that Kanak women were involved in "grassroots" activism from the mid-19th century, when they tried to hide their husbands and children from the French armies. More recently, they fought the prohibition against contraception imposed by the French and supported and participated in opposition to French armed forces.[5]

In 1974 Ounei was arrested and beaten for expressing her opposition to the celebration of the colonization of New Caledonia on 24 September 1853.[6] In prison Ounei developed the concept of the feminist Groupe de femmes kanak exploitées en lutte (GFKEL) with other women including Déwé Gorodey, at that time the only Kanak woman to have ever received a college education.[7] The organization was intended to ensure equal treatment of women within the independence movement.[8] In 1984 GFKEL was one of the founding organizations of the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS: Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste).[1] Around 1986 the GFKEL became dormant.[9] Ounei wrote in 1986,

For us Kanak women, we have to politicize everything to get a just society. Their [Kanak men] attitude to the women is just exactly that of the white settlers, the rich folks, the army. Other political movements created their own women's section to cook for the men when they had general assemblies. We wanted a group to fight against that. Women wanted to talk about contraception. Before, in our society, we always had contraception. If a woman wanted to have children she could--if not she could go to one of the older women who knew what herbs or leaves she could use. But since the church came, it is a crime to talk about contraception, so we organize to fight that.[10]

In her 1990 book Kanaky Ounei noted that there were few women in the independence movement, and some male members tried to discourage them, saying it was against the custom for women to speak. Some women also viewed them negatively because they would discuss subjects like contraception.[11] Ounei expressed hostility to the Christian Church, which she felt had corrupted the custom and perpetrated male dominance.[12] She wrote,

There are some who believe that the custom says women's position is below the man. There is nothing says that: that in the custom women should be beaten or raped, or she should shut her mouth when her husband is around. There is nothing in the custom says that. That is a big lie. It is just to protect themselves, their power... We have to fight hard to make men understand that a free Kanaky is for everyone. Not only independence for men but independence for everyone. I try to change the attitudes of my brothers but I can't hate them.[11]

New Zealand and elsewhere

Susanna Ounei lost her job in Nouméa due to her work for Kanak independence, and early in 1984 went to New Zealand to learn English.[1] The Council of Organisations for Relief Services Overseas (CORSO) and the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) sponsored her in New Zealand, and she was later involved in projects with both organizations. Susanna lived in New Zealand, attended the University of Canterbury, where she earned a degree in sociology, and published several works about Kanak independence. In 1985 she attended the Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi, where she met the activist Angela Davis. In the 1980s she became involved in the Maori sovereignty movement in New Zealand, speaking at many hui.[2] She married a New Zealander, David Small, in 1986.[1] Two of Ounei's brothers were killed by French troops during New Caledonia resistance activities in April 1988.[13]

In the 1990s the Pacific Concerns Resource Centre, the secretariat of the NFIP, moved from Auckland, New Zealand to Suva, Fiji.[2] Susanna was appointed assistant director of decolonization.[1] Omomo Melen Pacific (Women Lifeblood of the Pacific) was created in a December 1994 meeting convened by Ounei as a network of activists from Australia, New Zealand, Bougainville, East Timor, New Caledonia, Tahiti and West Papua. The immediate goal was the ensure visible participation at the forthcoming Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. Ounei had carefully selected members whom she felt to have sound political views. The network struggled with logistic problems, language barriers and lack of funding, but the members were enthusiastic.[14]

The Omomo Melen project aimed to ensure that the Beijing conference addressed questions of Pacific decolonization.[15] In 1995 Ounei represented the project at the United Nations headquarters in New York during the final preparatory conference for Beijing. She ensured that the draft Global Plan of Action (GPA) included a statement on the situation of women in colonized territories.[15] She spoke at the 1995 UN NGO Forum on Women, where she said the accords with the French in the late 1980s had not seriously addressed the concerns of Kanak women. In her view the neocolonial relations developed during the French occupation of New Caledonia had resulted in domestic violence, rape and a division of labour that forced women into subordinate roles.[16] In Beijing Ounei spoke at a Forum plenary session on "Obstacles to Peace and Human Security", and participated in a global tribunal arranged by the Asian Women’s Human Rights Council. At these events she forcibly drew attention to the Pacific nuclear testing issue.[15]

Ounei's marriage broke down in 1997. She remained on Ouvéa until 2000 when she returned to Wellington, New Zealand, with her two adopted children.[1] She died in Wellington on 21 June 2016, aged 70.[2]

Publications

- Susanna Ounei (1985), For Kanak Independence, The Fight Against French Rule in New Caledonia, Auckland: Labour Publishing Co-operative Society Ltd

- Susanna Ounei (1987), "Kanak Women: Out of the Kitchen Into the Struggle", in Davies (ed.), Third World - Second Sex, London: Zed Books

- Susanna Ounei (1990), Kanaky

- Susanna Ounei-Small (1992), "Kanaky: The 'Peace' Signed with Our Blood", in David Robie (ed.), Tu Galala: Social Change in the Pacific, Wellington & Annandale: Bridget Williams & Pluto

- Susanna Ounei (1992), "For an Independent Kanaky", in Lenora Foerstal; Angela Gilliam (eds.), Confronting the Margaret Mead Legacy: Scholarship, Empire and the South Pacific, Philadelphia: Temple University Press

- Susanna Ounei (1995), "New Caledonia", in International Commission of Jurists (ed.), Women and the Law in the Pacific, Geneva: International Commission of Jurists

- Susanna Ounei (1998), "Free Kanaky", in Zohl de Ishtar (ed.), Pacific Women Speak Out for Independence and Denuclearisation, Christchurch

Notes

- Kanak independence activist Susanna Ounei ...

- Teaiwa 2016.

- Dibblin 1998, p. 230.

- Chappell 2010, p. 52.

- Diamond 2013, PT219.

- Foerstel 1994, p. 159.

- Foerstel 1994, pp. 159–160.

- Foerstel 1994, p. 160.

- Henningham 1992, p. 80.

- Ounei 1986, p. 10.

- Ishtar 1994, p. 246.

- Ishtar 1994, p. 219.

- Foerstel 1994, p. xxiv.

- Riles 2001, p. 175.

- George 2012, p. 126.

- West 2014, p. xxxv.

Sources

- Chappell, David (2010), "A "Headless" Native Talks Back: Nidoish Naisseline and the Kanak Awakening in 1970s New Caledonia", The Contemporary Pacific, University of Hawai'i Press, 22 (1), JSTOR 23724721

- Diamond, Marie Josephine (2013-06-29), Women and Revolution: Global Expressions, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 978-94-015-9072-3, retrieved 2017-11-12

- Dibblin, Jane (1998-04-21), Day of Two Suns: U.S. Nuclear Testing and the Pacific Islanders, New Amsterdam Books, ISBN 978-1-4617-3270-9, retrieved 2017-11-12

- Foerstel, Lenora (1994-07-28), Confronting Margaret Mead: Scholarship, Empire, and the South Pacific, Temple University Press, ISBN 978-1-56639-261-7, retrieved 2017-11-11

- George, Nicole (2012-11-01), Situating Women: Gender Politics and Circumstance in Fiji, ANU E Press, ISBN 978-1-922144-15-7, retrieved 2017-11-12

- Henningham, Stephen (1992), France and the South Pacific: A Contemporary History, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1305-5, retrieved 2017-11-12

- Ishtar, Zohl Dé (1994), Daughters of the Pacific, Spinifex Press, ISBN 978-1-875559-32-9, retrieved 2017-11-12

- "Kanak independence activist Susanna Ounei has died", CathNews NZ and Asia Pacific, 1 July 2016, retrieved 2017-11-11

- Ounei, Susanna (January 1986), "Kanak women's struggle", Off Our Backs, off our backs, inc., 16 (1, Latin American Women), JSTOR 25794750

- Riles, Annelise (2001), The Network Inside Out, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-08832-7, retrieved 2017-11-12

- Teaiwa, Dr. Teresia (28 June 2016), "Tribute to Kanak independence activist Susanna Ounei", Scoop Media, retrieved 2017-11-11

- West, Lois (2014-01-21), Feminist Nationalism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-66967-5