Sue Williamson

Sue Williamson (born 1941) is an artist and writer based in Cape Town, South Africa.

Sue Williamson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 January 1941 |

| Nationality | South African |

| Education | Art Students League of New York and Michaelis School of Fine Arts at the University of Cape Town |

| Known for | installation art, photography, video art |

| Awards | Visual Arts Research Award, Smithsonian Institution (2007) |

%2C_Soweto_(2013)_Archival_ink_on_archival_paper%2C_Image_58x39cm%2C_Paper_71%2C5x51%2C5_cm_Edition_of_6.jpg)

Life

Sue Williamson was born in Lichfield, England in 1941. In 1948 she immigrated with her family to South Africa. Between 1963 and 1965 she studied at the Art Students League of New York. In 1983 she earned her Advanced Diploma in Fine Art from the Michaelis School of Fine Art, Cape Town.[1] In 2007 she received the Visual Arts Research Award from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C and in 2011[2] the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Creative Arts Fellowship.[3] In 2013 she was a guest curator of the summer academy at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern.

Work

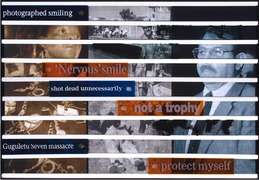

Williamson's work engages with themes related to memory and identity formation. Trained as a printmaker, Williamson has worked across a variety of media including archival photography, video, mixed media installations, and constructed objects. Her earlier work, such as Mementos of District Six (1993), Out of the Ashes (1994), and R.I.P. Annie Silinga (1995), are a few early examples that convey her investment in the recuperation and interrogation of South African history.

Since the coming of democracy in 1994, in works such as Truth Games, Can’t Forget, Can't Remember, Messages from the Moat, and Better Lives, Williamson has continued to focus on such issues as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, slavery, and immigration.

In No More Fairy Tales (2016), a series of five two-channel video conversations highlights the reality of daily life in South Africa twenty years after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was embarked upon as a process which many hoped then would bring healing to the stricken country. In mid 2015, with student unrest that swept across the country it became clear that the wounds had not healed. One of the first completed videos - It's a pleasure to meet you - follows a conversation between two young people in their twenties - Candice Mama and Siyah Mgoduka - whose fathers were killed by apartheid assassin Eugene de Kock.

In One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale (2018), the names given by slave masters, ages, sexes, and places of birth, along with the names of buyers and sellers, prices paid, and the date of purchase of people from the slave trade in India are written in black ink on cotton shirts. The shirts are imported from India, dipped into muddy waters drawn from the Cape Coast Castle, and hung around the grounds until Heritage Day, September 24, 2019. They are then taken down and returned to India, where they are washed clean and rehung as an installation at the Aspinwall House in Kochi. These people were transported by Dutch East India Company to work at the Cape Town Castle and the Company's Gardens. One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale Williamson incorporates the history and memory of the slave trade in order to transform the stigmatizing history into a history that can address and combat global inequalities. Upon opening the exhibition, WIlliamson read extracts of historical accounts while a woman picked up each shirt, read out the information on it, and then took it inside to be dipped in mud and hung on a washing line. Art brings history of slave trade to life The installation tells a story of loss and symbolizes the essence of a person that is floating in the wind, but all that remains is their memory. Sue Williamson, 'One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale'

Williamson's ethical lens has expanded in more recent years to consider social issues on a more global scale, as in her work 'Other Voices, Other Cities, from 2009.

Public collections

Williamson's work is in the collection of a variety of museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York,[4] the National Museum of African Art - Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., the South African National Gallery in Cape Town, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Williamson has also participated in group exhibitions including The Short Century (2001), Liberated Voices (1999), the Johannesburg Art Biennale (in 1997 and 1995), the Havana Biennale (1994), and the Venice Biennale (1993).

Selected exhibitions

- 2000 Messages from the Moat, Archive Building, Den Haag, Netherlands

- 2001 Can’t forget, can’t remember, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

- 2002 The Last Supper Revisited National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., USA

- 2002 From the Inside, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

- 2003 Sue Williamson: Selected Work, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Brussels, Belgium*

- 2004 Messages from the Moat, Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town

- 2005 Hotels and Better Lives, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

- 2007 Hotels and Better Lives, Wertz Gallery, Atlanta, USA

- 2009 The Truth is on the Walls, Wifredo Lam Centre, Havana, 10th Havana Biennale, Cuba*

- 2009 Other Voices, Other Cities, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

- 2011 Voices, Goodman Gallery, Cape Town

- 2012 The Mothers: a 31 Year Chronicle, Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town

- 2013 All Our Mothers Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

- 2014 There's something I must tell you, Iziko Slave Lodge, Cape Town

- 2014 Sue Williamson, Goodman Gallery stand, Frieze Masters, London

- 2015 Other Voices, Other Cities, SCAD Museum, Savannah, Georgia, USA

- 2016 The Past Lies Ahead, Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

- 2016 Other Voices, Other Cities, SCAD Atlanta: Gallery 1600, Georgia, USA

- 2016 No More Fairy Tales, Johannes Stegmann Art Gallery, Bloemfontein,

- 2017 Can't Forget, Can't Remember, Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 2017 Being There: South Africa, a contemporary scene, Foundation Louis Vuitton, Paris

- 2017 "Messages from the Atlantic Passage", Installation, Basel Unlimited, Basel, Switzerland

- 2017 Other Voices, Other Cities: Delhi, Prameya Art Foundation

- 2017 Women House, Monnaie de Paris, Paris France

Awards and fellowships

- 2005 Lucas Artists Residency Fellowship. Montalvo Art Center, California, USA

- 2007 Goodman Gallery Award, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 2007 Visual Artist Research Award Fellowship, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, USA

- 2011 Bellagio Creative Arts Fellowship, Italy, Rockefeller Foundation

Publications

In 1997 Sue Williamson established ArtThrob, a prominent online publication that features the work of contemporary South African artists. ArtThrob has been nominated three times as a finalist for the Arts and Culture Trust Award, and in 1999 was nominated for the United Nations for best cultural website.

- South African Art Now. New York: Collins Design. 2009. ISBN 978-0061343513.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fabienne Dumont; Linda Givon, eds. (2003). Sue Williamson: Selected Work. Juta and Company Ltd. ISBN 978-1-919930-24-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Art in South Africa: The Future Present. Cape Town: David Philip. 1996.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Resistance Art in South Africa. Juta and Company Ltd. 2010. ISBN 978-1-919930-69-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- "insights: Sue Williamson". Smithsonian Institution. n.d. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Guest Curator at the Wayback Machine (archived March 1, 2013)

- Sue Williamson at the Wayback Machine (archived March 1, 2013)

- n.d. "Sue Williamson". MoMA. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

General references

- Grania Ogilvy, Dictionary of South African Sculptors and Painters, Everard Read, 1989.

- Betty La Duke, Africa through the Eyes of Women Artists, Africa World Press, 1991.

- Richard J Powell, Black Art and Culture in the 20th Century, World of Art Series, Thames & Hudson, 1997.

- Philippa Hobbs & Elizabeth Rankin, Printmaking in a transforming South Africa, David Philip Publishers, Cape Town, 1997.

- Olu Oguibe & Okwui Enwezor, Reading the Contemporary: African Art from Theory to Marketplace, MIT Press, 1999.

- Sidney Littlefield, Contemporary African Art, Thames & Hudson, 1999.

- N'Gone Fall & Jean Pivin, Anthologie de l'Art Africain du Xxe Siecle, Revue Noir, 2001.

- Gurney, Kim (November 2003). "Sue Williamson". Artthrob (75). Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Nicholas M. Dawes, Sue Williamson: Selected Work, Juta and Company Ltd, 2003.

- Emma Bedford and Sophie Perryer, 10 Years 100 Artists: Art In A Democratic South Africa, Struik, 2004.

- Petra Stegmann, Sue Williamson in Culturebase, 2007.

- Jason, Stefanie (31 May 2013). "Sue Williamson celebrates an enduring female legacy". The M&G Online. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Gevisser, Mark (2015). Sue Williamson: Life and Work. Skira. ISBN 978-88-572-2867-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)