Stylite

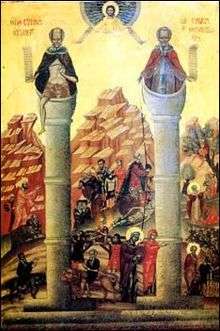

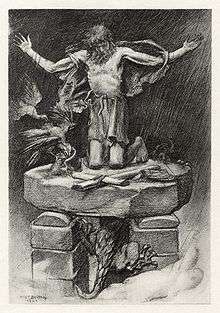

A stylite (from Greek στυλίτης, stylitēs, "pillar dweller", derived from στῦλος, stylos, "pillar", Classical Syriac: ܐܣܛܘܢܐ ʼasṯonáyé) or pillar-saint is a type of Christian ascetic who lives on pillars, preaching, fasting and praying. Stylites believe that the mortification of their bodies would help ensure the salvation of their souls. Stylites were common in the early days of the Byzantine Empire. The first known stylite was Simeon Stylites the Elder who climbed a pillar in Syria in 423 and remained there until his death 37 years later.

Ascetic precedents

Palladius of Galatia tells of Epidius, a hermit in Palestine who dwelt in a mountaintop cave for twenty-five years until his death.[1] St. Gregory of Nazianzus (Patrologia Graeca 37, 1456) speaks of a solitary who stood upright for many years together, absorbed in contemplation, without ever lying down. Theodoret claimed that he had seen a hermit who had passed ten years in a tub suspended in midair from poles (Philotheus, chapter 28).

Simeon Stylites and his contemporaries

In 423 Simeon Stylites the Elder took up his abode on the top of a pillar. Critics have recalled a passage in Lucian (De Syria Dea, chapters 28 and 29) which speaks of a high column at Hierapolis Bambyce to the top of which a man ascended twice a year and spent a week in converse with the gods, but the Catholic Encyclopedia argues that it is unlikely that Simeon had derived any suggestion from this pagan custom. In any case Simeon had a continuous series of imitators, particularly in Syria and Palestine. Daniel the Stylite may have been the first of these, for he had been a disciple of Simeon and began his rigorous way of life shortly after his master died. Daniel was a Syrian by birth but he established himself near Constantinople, where he was visited by both the Emperor Leo and the Emperor Zeno. Simeon the Younger, like his namesake, lived near Antioch; he died in 596, and had for a contemporary a hardly less famous Stylite, Saint Alypius, whose pillar had been erected near Hadrianopolis in Paphlagonia. Alypius, after standing upright for 53 years, found his feet no longer able to support him, but instead of descending from his pillar lay down on his side and spent the remaining fourteen years of his life in that position. Roger Collins, in his Early Medieval Europe, tells us that in some cases two or more pillar saints of differing theological viewpoints could find themselves within calling distance of each other, and would argue with one another from their columns.

Other stylites

Saint Luke the Younger, another famous pillar hermit, lived in the 10th century on Mount Olympus, though he also seems to have been of Asiatic parentage. Daniel the Stylite lived on his pillar for 33 years after being blessed by and receiving the cowl of St. Simeon the Stylite. There were many others besides these who were not so famous, and even female Stylites are known to have existed. One or two isolated attempts seem to have been made to introduce this form of asceticism into the West, but it met with little favour. In the East cases were found as late as the 12th century; in the Russian Orthodox Church the practice continued until 1461, and among the Ruthenians even later. For the majority of the pillar hermits the extreme austerity of the lives of the Simeons and of Alypius was somewhat mitigated. Upon the summit of some of the columns a tiny hut was erected as a shelter against sun and rain, and other hermits of the same class among the Miaphysites lived inside a hollow pillar rather than upon it. Nonetheless, the life was one of extraordinary endurance and privation.

In recent centuries this form of monastic asceticism has become virtually extinct. However, in modern-day Georgia, Maxime Qavtaradze, a monk of the Orthodox Church, has lived on top of Katskhi Pillar for 20 years, coming down only twice a week. This pillar is a natural rock formation jutting upward from the ground to a height of approximately one hundred and forty feet. Evidence of use by stylites as late as the 13th century has been found on the top of the rock. With the aid of local villagers and the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation of Georgia, Qavtaradze restored the 1200-year-old monastic chapel on the top of the rock. A film documentary on the project was completed in 2013.[2]

Popular culture

- The Vertigo stunt performed by David Blaine on 22 March 2002 was in part inspired by the Pillar-Saints, as he declared in the TV documentary about this stunt.

- A song named "Stylitis" ("Stylite") was written by the Greek singer-songwriter Thanasis Papakonstantinou in 1998.

Fiction

- In Herman Melville's Moby Dick the narrator calls St. Stylites a "dauntless stander-of-mast-heads" who "literally died at his post."

- In Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, the title character encounters a stylite who prays by metania and uses the pedal motion to sew shirts describes as "St. Stylites".

- Umberto Eco's Baudolino temporarily becomes a stylite towards the end of the book.

- Luis Buñuel's Simón del desierto (Simon of the Desert, 1965) is a humorous film about the life of a stylite.

- In Terry Pratchett's Small Gods, a book from the Discworld series, a character named St. Ungulant lives on top of a pole.

- In the episode Souvenirs of the TV series M*A*S*H, Cpl. Klinger sets a pole sitting record.

- In Anatole France's Thaïs Paphnuce on his path to damnation becomes a stylite but unwittingly falling to temptation.

- In Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls, Pole-Standing was a rite of passage for a native tribe.

- A Stylite-type figure is featured in the first two episodes of the second season of the HBO series The Leftovers.

- In Two For Joy, the second book in Mary Reed and Eric Mayer's John, the Lord Chamberlain series of historical mystery novels set in 6th Century Constantinople, three stylites in a row spontaneously combust during a lightning storm leaving John the Lord Chamberlain suspecting foul play.

See also

References and sources

References

- Palladius of Galatia (1918). The Lausiac History of Palladius. trans., W. K. Lowther Clarke. The Macmillan Company. pp. 154–155. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- "Upon this Rock (2013) – IMDb". IMDb. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

Sources

- Frederick Lent, translator, The Life of Saint Simeon Stylites: A Translation of the Syriac in Bedjan’s Acta Martyrum et Sanctorum, 1915. Reprinted 2009. Evolution Publishing, ISBN 978-1-889758-91-6.

- Last of the Stylites

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stylites. |

| Look up stylite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |