Structural dynamics

Structural dynamics is a type of structural analysis which covers the behavior of a structure subjected to dynamic (actions having high acceleration) loading. Dynamic loads include people, wind, waves, traffic, earthquakes, and blasts. Any structure can be subjected to dynamic loading. Dynamic analysis can be used to find dynamic displacements, time history, and modal analysis.

Structural analysis is mainly concerned with finding out the behavior of a physical structure when subjected to force. This action can be in the form of load due to the weight of things such as people, furniture, wind, snow, etc. or some other kind of excitation such as an earthquake, shaking of the ground due to a blast nearby, etc. In essence all these loads are dynamic, including the self-weight of the structure because at some point in time these loads were not there. The distinction is made between the dynamic and the static analysis on the basis of whether the applied action has enough acceleration in comparison to the structure's natural frequency. If a load is applied sufficiently slowly, the inertia forces (Newton's first law of motion) can be ignored and the analysis can be simplified as static analysis.

A static load is one which varies very slowly. A dynamic load is one which changes with time fairly quickly in comparison to the structure's natural frequency. If it changes slowly, the structure's response may be determined with static analysis, but if it varies quickly (relative to the structure's ability to respond), the response must be determined with a dynamic analysis.

Dynamic analysis for simple structures can be carried out manually, but for complex structures finite element analysis can be used to calculate the mode shapes and frequencies.

Displacements

A dynamic load can have a significantly larger effect than a static load of the same magnitude due to the structure's inability to respond quickly to the loading (by deflecting). The increase in the effect of a dynamic load is given by the dynamic amplification factor (DAF) or dynamic load factor (DLF):

where u is the deflection of the structure due to the applied load.

Graphs of dynamic amplification factors vs non-dimensional rise time (tr/T) exist for standard loading functions (for an explanation of rise time, see time history analysis below). Hence the DAF for a given loading can be read from the graph, the static deflection can be easily calculated for simple structures and the dynamic deflection found.

Time history analysis

A full time history will give the response of a structure over time during and after the application of a load. To find the full time history of a structure's response, you must solve the structure's equation of motion.

Example

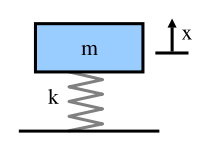

A simple single degree of freedom system (a mass, M, on a spring of stiffness k, for example) has the following equation of motion:

where is the acceleration (the double derivative of the displacement) and x is the displacement.

If the loading F(t) is a Heaviside step function (the sudden application of a constant load), the solution to the equation of motion is:

where and the fundamental natural frequency, .

The static deflection of a single degree of freedom system is:

so we can write, by combining the above formulae:

This gives the (theoretical) time history of the structure due to a load F(t), where the false assumption is made that there is no damping.

Although this is too simplistic to apply to a real structure, the Heaviside step function is a reasonable model for the application of many real loads, such as the sudden addition of a piece of furniture, or the removal of a prop to a newly cast concrete floor. However, in reality loads are never applied instantaneously – they build up over a period of time (this may be very short indeed). This time is called the rise time.

As the number of degrees of freedom of a structure increases it very quickly becomes too difficult to calculate the time history manually – real structures are analysed using non-linear finite element analysis software.

Damping

Any real structure will dissipate energy (mainly through friction). This can be modelled by modifying the DAF

where and is typically 2–10% depending on the type of construction:

- Bolted steel ~6%

- Reinforced concrete ~5%

- Welded steel ~2%

- Brick masonry ~10%

Methods to increase damping

One of the widely used methods to increase damping is to attach a layer of material with a high Damping Coefficient, for example rubber, to a vibrating structure.

Modal analysis

A modal analysis calculates the frequency modes or natural frequencies of a given system, but not necessarily its full-time history response to a given input. The natural frequency of a system is dependent only on the stiffness of the structure and the mass which participates with the structure (including self-weight). It is not dependent on the load function.

It is useful to know the modal frequencies of a structure as it allows you to ensure that the frequency of any applied periodic loading will not coincide with a modal frequency and hence cause resonance, which leads to large oscillations.

The method is:

- Find the natural modes (the shape adopted by a structure) and natural frequencies

- Calculate the response of each mode

- Optionally superpose the response of each mode to find the full modal response to a given loading

Energy method

It is possible to calculate the frequency of different mode shape of system manually by the energy method. For a given mode shape of a multiple degree of freedom system you can find an "equivalent" mass, stiffness and applied force for a single degree of freedom system. For simple structures the basic mode shapes can be found by inspection, but it is not a conservative method. Rayleigh's principle states:

"The frequency ω of an arbitrary mode of vibration, calculated by the energy method, is always greater than – or equal to – the fundamental frequency ωn."

For an assumed mode shape , of a structural system with mass M; bending stiffness, EI (Young's modulus, E, multiplied by the second moment of area, I); and applied force, F(x):

then, as above:

Modal response

The complete modal response to a given load F(x,t) is . The summation can be carried out by one of three common methods:

- Superpose complete time histories of each mode (time consuming, but exact)

- Superpose the maximum amplitudes of each mode (quick but conservative)

- Superpose the square root of the sum of squares (good estimate for well-separated frequencies, but unsafe for closely spaced frequencies)

To superpose the individual modal responses manually, having calculated them by the energy method:

Assuming that the rise time tr is known (T = 2π/ω), it is possible to read the DAF from a standard graph. The static displacement can be calculated with . The dynamic displacement for the chosen mode and applied force can then be found from:

Modal participation factor

For real systems there is often mass participating in the forcing function (such as the mass of ground in an earthquake) and mass participating in inertia effects (the mass of the structure itself, Meq). The modal participation factor Γ is a comparison of these two masses. For a single degree of freedom system Γ = 1.

External links

- DYSSOLVE: Dynamic System Solver – An encrypted-source, lightweight, free-of-charge software that can be used to solve basic structural dynamics problems.

- Structural Dynamics and Vibration Laboratory of McGill University

- Frame3DD open source 3D structural dynamics analysis program

- Frequency response function from modal parameters

- Structural Dynamics Tutorials & Matlab scripts

- AIAA Exploring Structural Dynamics (http://www.exploringstructuraldynamics.org/ ) – Structural Dynamics in Aerospace Engineering: Interactive Demos, Videos & Interviews with Practicing Engineers