Stephen Atkins Swails

Stephen Atkins Swails (23 February 1832 – 17 May 1900) was a soldier in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Although originally enlisting as a private, he was the first African-American soldier promoted to commissioned rank, as a line officer, in that conflict, as evidenced by the U.S. War Department's initial refusal of that promotion due to his "African descent."[1]

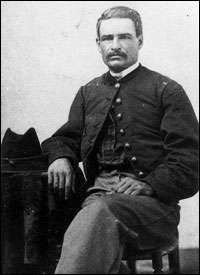

Stephen A. Swails | |

|---|---|

1st LT. Stephen Swails, 1864 | |

| Born | February 23, 1832 Columbia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | May 17, 1900 (aged 68) Kingstree, South Carolina |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1863–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Swails was a free black who was so light in coloring that he was often mistaken as white.[1] He was single and employed mostly as a waiter in Cooperstown, New York at the start of the Civil War, and although he fathered several children by Sarah Thompson, they never married.[2] His enlistment papers state he was employed as a boatman in Elmira, New York when he joined the army.[3] In 1863, he answered Frederick Douglass' call to arms and joined the 54th Massachusetts when it began forming, and served in that regiment, eventually being commissioned as an officer, until the end of the war. After the war, he settled in South Carolina and later Washington, D.C., becoming a lawyer and politician.

Civil War career

Stephen Swails was a member of the 54th Massachusetts, enlisting and then rising through the ranks to receive a commission. He joined Company F of the 54th on 23 April 1863 and was soon appointed the company's first sergeant.[3] Due to the loss of men in the assault on Fort Wagner, and when Colonel Edward Hallowell assumed command of the 54th, Swails was appointed acting sergeant-major of the 54th on 12 November 1863.[4]

In early 1864, the regiment was posted to Florida as part of General Truman Seymour's expedition. On 20 February, while still performing duty as the regiment's sergeant-major, Swails was wounded in the head at the Battle of Olustee. Setting out toward the Union supply point at Sanderson, he soon fell unconscious on the road, but was placed on a cart by one of the 54th's officers.[5] On 26 February 1864, Colonel Hallowell,

...In accordance with the desire of his officers as well as his own... recommended to Governor Andrew that Sergeant Swails be commissioned in recognition of many soldiery qualities and his gallantry at Olustee.[6]

On 26 March 1864, the regiment received a list of promotions approved by Governor Andrew, one of which was Swails' promotion to 2nd lieutenant.[7] Thus began the fight to secure for Stephen Swails what may have been the first commission as a line officer given to an African American in the Union Army.[2][8][9]

In May 1864, while the regiment was posted on Morris Island, South Carolina, during the siege of Charleston, Swails' application to muster as a 2nd lieutenant with the regiment was refused by the War Department. The reason given was "Lieutenant Swails' African descent." Colonel William Gurney, the post commander, ordered Swails to remove his officer's uniform and reassume duties as an enlisted man. However, Colonel Hallowell obtained a furlough for Swails and sent him, along with all the necessary paperwork, to Major General John Foster, commander of the Department of the South. Once there, Lieutenant Swails presented his case, and received General Foster's recommendation, which was forwarded to higher authority.[1] Lieutenant Swails then returned to duty with the regiment. In addition to correspondence between the Department of the South, Governor Andrew and the War Department, Lieutenant Swails also received a furlough to travel to Washington to present his own case. He then returned to duty. Finally, on 17 January 1865, orders were received from the War Department, authorizing Stephen Swails to muster as a 2nd lieutenant with the regiment, ending almost a year-long struggle on his behalf by Colonel Hallowell, Governor Andrew and the officers of the 54th. During this period, Swails continued to perform his duties as a line officer in Company D and participated in numerous actions.[9]

On 11 April 1865, near Camden, South Carolina, Lieutenant Swails was wounded for a second time. While the 54th was on reconnaissance near a railroad junction, several locomotives, one with the steam up, were observed after dark. A detachment led by Lieutenant Swails rushed the trains and captured them. As Lieutenant Swails entered the cab of one locomotive, he waved his hat in triumph. This action drew the attention of the sharpshooters that he had deployed to shoot the trainmen if they tried to escape. Mistaking him for a white engineer, they fired at and wounded him.[10]

Second Lieutenant Swails was promoted to 1st lieutenant on 28 April 1865 and discharged on 20 August 1865, when the regiment mustered out at Boston.[3]

Post-war career

After the war, Swails worked as an agent for the Freedmen's Bureau, practiced law in the South, and became active in the political life of South Carolina. He married Susan Aspinall, a mixed-race Charlestonian, who bore him three children, Irene, Stephen Jr. and Florine. (Because Sarah Thompson bore him a son named Stephen Jr., he had two children with that name.) He was the mayor of Kingstree, where he lived from 1868 to 1879. He served as a state senator for ten years (1868–1878), including three terms as president pro tem.[11]

Swails was a delegate to the 1868, 1872 and 1876 Republican national conventions. He became a member of the U.S. Electoral College, and also edited a newspaper, the Williamsburg Republican.[2][8]

He was forced out of politics after Reconstruction. After a white mob tried to assassinate him, he resigned from office and, through his Republican connections, obtained jobs in Washington, D.C. with the U.S. Postal Service and the United States Treasury Department.[2][8]

Stephen Swails is buried in the Friendly Society Cemetery, Charleston, South Carolina.[11]

Family

Because of his complicated private life, Stephen Swails' descendants are plentiful, and live in Toronto, upstate New York, Philadelphia, and Atlanta.

One of his surviving grandchildren was James Swails Sr., of Rochester, New York, who died in 2004. His granddaughter, Carolyn Janet Rollins, and another grandson, Robert Swails, are also deceased. Caroline Janet Rollins was a counselor in New Jersey. She married Joseph Tyler Jefferson. They have eight surviving children. Robert Swails Rollins was a Doctor of Internal Medicine, graduated from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. He had two sons and a daughters and lived on Long Island, New York. Dr. Robert Swails Rollins was a flight surgeon in the United States Air Force and, after military service, had a practice on Long Island, New York.

Citations

- Emilio 1995, p. 194.

- AAHI 2010.

- Emilio 1995, p. 336.

- Emilio 1995, p. 135.

- Emilio 1995, pp. 165, 169.

- Emilio 1995, p. 179.

- Emilio 1995, p. 183.

- Cornish 2006.

- Emilio 1995, p. 268.

- Emilio 1995, p. 296.

- Swain and Bullard 2010.

References

- AAHI (2010). "Lt. Stephen Swails". African American Historical Alliance. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- Egerton, Douglas (2016). Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments That Redeemed America. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465096640.

- Cornish, Audie (1 November 2006). "Black Civil-War Soldier Gets Overdue Honors". NPR. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- Emilio, Luis (1893, 1995). A Brave Black Regiment: The History of the 54th Massachusetts, 1863–1865. Da Capo Press, New York. ISBN 0-306-80623-1. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - Swain, Craig; David Bullard (24 February 2010). "Stephen A. Swails House". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 10 September 2010.