Stecknitz Canal

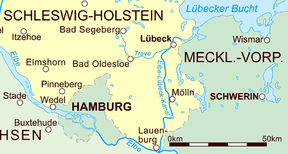

The Stecknitz Canal (German: Stecknitzfahrt) was an artificial waterway in northern Germany which connected Lauenburg and Lübeck on the Old Salt Route by linking the tiny rivers Stecknitz (a tributary of the Trave) and Delvenau (a tributary of the Elbe), thus establishing an inland water route across the drainage divide from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea. Built between 1391 and 1398, the Stecknitz Canal was the first European summit-level canal and one of the earliest artificial waterways in Europe.[1] In the 1890s the canal was replaced by an enlarged and straightened waterway called the Elbe–Lübeck Canal, which includes some of the Stecknitz Canal's watercourse.[2]

| Stecknitz Canal | |

|---|---|

The modern Elbe–Lübeck Canal in eastern Schleswig-Holstein | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 60 miles (97 km) (Man-made segment ran for 11.5 kilometres (7.1 mi)) |

| Locks | 17 (originally 13) |

| Original number of locks | 13 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 56 ft (17 m) |

| Status | replaced by Elbe–Lübeck Canal |

| History | |

| Date of act | 1390 |

| Construction began | 1391 |

| Date completed | 1398 |

| Date closed | 1893 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Lauenburg (Elbe) |

| End point | Lübeck (Trave) |

The original artificial canal was 0.85 metres (33 in) deep and 7.5 metres (25 ft) wide; the man-made segment ran for 11.5 kilometres (7.1 mi), with a total length of 97 kilometres (60 mi) including the rivers it linked. The canal included seventeen wooden locks (of which the Palmschleuse at Lauenburg still exists) that managed the 13-metre (43 ft) elevation difference between its endpoints and the highest central part, the Delvenaugraben.[3]

History

In the Middle Ages the trade between the North Sea and Baltic Sea grew dramatically, but the sea journey through Øresund, increasingly important to commercial shipping since the thirteenth century, was time-consuming and dangerous. Therefore, the emerging Hanseatic city of Lübeck and Eric IV of Saxe-Lauenburg agreed in 1390 to cooperate in the construction of an artificial canal between the Elbe and the Baltic Sea.[4] Construction on the canal began in 1391; thirty barges carrying the first load of salt from Lüneburg reached Lübeck on 22 July 1398.[1]

The Stecknitz Canal soon replaced the existing overland cart road as the main transport mode for Lüneburg salt on the Old Salt Route. In Lübeck the salt was stored in vast salt warehouses and then transferred to ocean-going vessels for export throughout the Baltic region. In the reverse direction the Stecknitz barges transported cereals, furs, herring, ash, timber and other goods from Lübeck, which were reloaded in Lauenburg and transported down the Elbe to Hamburg. Later coal, peat, brick, limestone and gravel were added to the cargo. The importance of the canal was greatest in years in which Øresund was closed to merchant ships because of disputes over the Sound Dues and foreign shipping.[5]

In the fifteenth century traffic peaked, with more than 3,000 shipments of more than 30,000 tons of salt moving on the canal each year. This number declined by the seventeenth century to 400 to 600 shipments (5,000 to 7,000 tons). In 1789 there were still sixty-four shipments carrying approximately 680 tons of salt. Plans for a new Baltic–North Sea canal were proposed as early as the seventeenth century, but none was implemented until the end of the nineteenth century, when the new Elbe–Lübeck Canal was built using parts of the old route of the Stecknitz Canal.[6] For five hundred years the canal was used to transport the "white gold" and other goods; today the Palmschleuse lock in Lauenburg is one of the last remaining parts of the former canal, preserved as an historical monument.[7]

Technology

The Stecknitz Canal consisted of an 11.5-kilometre (7.1 mi) artificial waterway (the Delvenaugraben) linking two minor rivers, the north-flowing Stecknitz and south-flowing Delvenau. The man-made trench itself was about 85 centimetres (33 in) deep and 7.5 metres (25 ft) wide,[3] though it was enlarged between 1821 and 1823 to a depth of 144 centimetres (57 in) and a width of 12 metres (39 ft). Outside the artificial segment the canal followed the tortuous natural watercourses of the two rivers; as a result, the full journey from Lauenburg to Lübeck stretched to a distance of 97 kilometres (60 mi), even though the straight-line separation between the two cities is only 55 kilometres (34 mi). The journey along the canal often lasted two weeks or longer due to the number and primitive design of the locks and the difficulty of towing.[6]

The canal's course originally included thirteen locks, which later renovations increased to seventeen. Initially most were one-gate flash locks built into weirs (usually set below the mouth of a tributary creek), where water was dammed until a barge was ready to pass downriver.[2] In Lauenburg the initial course included one chamber lock (the Palmschleuse) because of a watermill whose operation would have been made impossible by a flash lock. Over the course of the canal's lifetime further flash locks were progressively converted to chamber locks until the 17th century.

The canal overcame the drainage divide between the North and Baltic Seas, with a summit height of 17 metres (56 ft) above sea level.[3] In order to supply the top portion of the canal with water, flow was diverted from Hornbeker Mühlenbach. To the north the canal descended to the Ziegelsee by the town of Mölln and then connected to the Stecknitz by a series of eight locks. The southern end of the artificial canal descended to the Delvenau through a staircase of nine locks.

Barges and drivers

The original salt barges measured roughly 12 metres (39 ft) by 2.5 metres (8.2 ft), with a 40-centimetre (16 in) draft when loaded to capacity with around 7.5 tons of salt, and required at least ten days to make the journey one way.[1][2] When traveling uphill or through chamber locks the barges had to be hauled by laborers or animals walking the towpath on the banks of the channel. By the nineteenth century newer vessel designs included rigging that eliminated the need for towing (with sufficient wind).

In Lauenburg and Lübeck the barges were unloaded and their contents transferred to ships for export down the Elbe and Trave. Stecknitz barge drivers were only permitted to own one barge each, so they could not acquire great wealth in the trade; in the long run this ensured their dependence upon the Lübeck salt merchants, who were not bound by any such limitations and amassed great fortunes. The guild of the Stecknitzfahrer (Stecknitz barge drivers) still exists today in Lübeck and meets annually at the Kringelhöge to celebrate the guild's history.[8]

Notes

- Zumerchik, John; Danver, Steven Laurence (2010). Seas and Waterways of the World: An Encyclopedia of History, Uses, and Issues. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 118, 121. ISBN 9781851097111. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Clarke, Michael. "Stecknitz Canal". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Stecknitzkanal". Brockhaus' Konversations-Lexikon (in German). 15 (14th ed.). Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus AG. 1908. p. 273. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Wehrmann, Carl Friedrich, ed. (24 June 1390). "No. 519 and 520". Urkundenbuch of the Town of Lübeck (in German). IV.

- Dollinger, Philippe (2012). Die Hanse (in German) (6th ed.). Kröner Verlag. p. 199. ISBN 9783520371065. Dollinger points out that the revenue from canal tolls doubled in 1428/29 after Øresund was closed.

- Kirby, David; Hinkkanen, Merja-Liisa (2000). The Baltic and North Seas. London and New York: Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 9781136169540. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- McNeil, Ian (2002). An Encyclopedia of the History of Technology. Routledge. ISBN 9781134981656. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Müller, Walter (2002). Die Stecknitzfahrt (in German) (3rd ed.). Büchen: Goedeke. ISBN 3-9802782-0-4.

References

- Boehart, William; Bornefeld, Cordula; Lopau, Christian (1998). "Die Geschichte der Stecknitz-Fahrt 1398–1998". Sonderveröffentlichungen des Heimatbund und Geschichtsvereins Herzogtum Lauenburg (in German). Schwarzenbek: Kurt Viebranz Verlag. 29. ISBN 3-921595-29-0.

- Dittmer, Hermann Carl (1860). Über die Betheiligung Lübecks bei der Lüneburger Saline (in German). Lübeck.

- Hagedorn, Bernhard (1915). "Die Entwicklung und Organisation des Salzverkehrs von Lüneburg nach Lübeck im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert". Zeitschrift des Vereins für Lübeckische Geschichte und Altertumskunde (in German). 17: 7–26.

- Müller, Walter; Happach-Kasan, Christel (1992). Der Elbe-Lübeck-Kanal. Die nasse Salzstraße (in German). Neumünster: Wachholtz Verlag. ISBN 3-529-05317-1.

- Packheiser, Michael, ed. (2000). "Die Zukunft liegt auf dem Wasser. 100 Jahre Elbe-Lübeck-Kanal". Kataloge der Museen in Schleswig-Holstein (in German). Lübeck: Steintor-Verlag. 54. ISBN 3-9801506-6-6.

- Röhl, Heinz; Bentin, Wolfgang (2003). Grenzen und Grenzsteine der (freien und) Hansestadt Lübeck (in German). Lübeck: Schmidt-Römhild. pp. 229–231. ISBN 3-7950-0788-7.

- Stolz, Gerd (1995). "Kleine Kanalgeschichte. Vom Stecknitzkanal zum Nord-Ostsee-Kanal. (Published on the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Kiel Canal on 21 June 1895)". Kleine Schleswig-Holstein-Bücher (in German). Heide: Boyens Buchverlag. 45. ISBN 3-8042-0672-7.

- Wellbrock, Kai. "Der Stecknitz-Delvenau-Kanal – Betrieb des ersten Scheitelkanals Europas mit Hilfe von Kammerschleusen?". Korrespondenz Wasserwirtschaft (in German) (8/12): 425–429.