Stanley Spencer

Sir Stanley Spencer, CBE RA (30 June 1891 – 14 December 1959) was an English painter. Shortly after leaving the Slade School of Art, Spencer became well known for his paintings depicting Biblical scenes occurring as if in Cookham, the small village beside the River Thames where he was born and spent much of his life. Spencer referred to Cookham as "a village in Heaven" and in his biblical scenes, fellow-villagers are shown as their Gospel counterparts. Spencer was skilled at organising multi-figure compositions such as in his large paintings for the Sandham Memorial Chapel and the Shipbuilding on the Clyde series, the former being a First World War memorial while the latter was a commission for the War Artists' Advisory Committee during the Second World War.

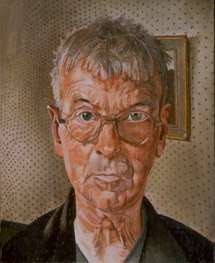

Sir Stanley Spencer | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1959 | |

| Born | Stanley Spencer 30 June 1891 |

| Died | 14 December 1959 (aged 68) Cliveden, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

Notable work | The Resurrection, Cookham; |

| Awards | RA 1950; CBE 1950; Knighted 1959 |

| Patron(s) | Louis and Mary Behrend |

As his career progressed Spencer often produced landscapes for commercial necessity and the intensity of his early visionary years diminished somewhat while elements of eccentricity came more to the fore. Although his compositions became more claustrophobic and his use of colour less vivid he maintained an attention to detail in his paintings akin to that of the Pre-Raphaelites.[1] Spencer's works often express his fervent if unconventional Christian faith. This is especially evident in the scenes that he based in Cookham which show the compassion that he felt for his fellow residents and also his romantic and sexual obsessions. Spencer's works originally provoked great shock and controversy. Nowadays, they still seem stylistic and experimental, while the nude works depicting his futile relationship with his second wife, Patricia Preece, such as the Leg of mutton nude, foreshadow some of the much later works of Lucian Freud. Spencer's early work is regarded as a synthesis of French Post-Impressionism, exemplified for instance by Paul Gauguin, plus early Italian painting typified by Giotto. In later life Spencer remained an independent artist and did not join any of the artistic movements of the period, although he did show three works at the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912.[2]

Early life

_by_Stanley_Spencer.jpg)

Stanley Spencer was born in Cookham, Berkshire, the eighth surviving child of William and Anna Caroline Spencer (née Slack).[3] His father, usually known as Par, was a music teacher and church organist. Stanley's younger brother, Gilbert Spencer (1892–1979), also became a notable artist, known principally for his landscape paintings. The family home, "Fernlea", on Cookham High Street, had been built by Spencer's grandfather Julius Spencer. Stanley Spencer was educated at home by his sisters Annie and Florence, as his parents had reservations about the local council school but could not afford private education for him. However, Gilbert and Stanley took drawing lessons from a local artist, Dorothy Bailey. Eventually, Gilbert was sent to a school in Maidenhead, but the family did not feel this would be beneficial for Stanley, who was developing into a solitary teenager given to long walks, yet with a passion for drawing. Par Spencer approached local landowners, Lord and Lady Boston, for advice, and Lady Boston agreed Stanley could spend time drawing with her each week. In 1907 Lady Boston arranged for Stanley to attend Maidenhead Technical Institute, where his father insisted he should not take any exams.[4]

From 1908 to 1912, Spencer studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, under Henry Tonks and others. His contemporaries at the Slade included Dora Carrington, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Mark Gertler, Paul Nash, Edward Wadsworth, Isaac Rosenberg and David Bomberg.[4] So profound was his attachment to Cookham that most days he would take the train back home in time for tea. It even became his nickname: his fellow student Christopher R. W. Nevinson dubbed him Cookham, a name which Spencer himself took to using for a time.[4] While at the Slade, Spencer allied with a short-lived group who called themselves the "Neo-Primitives" which was centred on Bomberg and William Roberts.[5]

In 1912 Spencer exhibited the painting John Donne Arriving in Heaven and some drawings in the British section of the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition organised by Roger Fry in London. The same year he painted The Nativity. for which he won a Slade Composition Prize and he also began painting Apple Gatherers, which was shown in the first Contemporary Art Society exhibition the following year. In 1914 Spencer completed Zacharias and Elizabeth and The Centurion's Servant. The latter painting featured not only Spencer himself as the servant, but also his brothers and the bed from his own nursery.[6] He also began work on a self-portrait. Self-portrait (1914) was painted in Wisteria Cottage, a decaying Georgian house Spencer rented, from the local coalman in Cookham, for use as a studio. Painted with a mirror, the painting is bold and austere with a direct and penetrating gaze, softened by the deep shadow on the right hand side – the head fills the picture space and is painted one and a half times life size.[7] Apple Gatherers had been bought by the artist Henry Lamb, who promptly sold it to the art collector Edward Marsh. Marsh later bought Self-portrait and considered it to be "masterly...glowing with genius."[4]

First World War

At the start of the First World War Spencer was keen to enlist but his mother persuaded him, given his poor physique, to apply for ambulance duties.[8] In 1915 Spencer volunteered to serve with the Royal Army Medical Corps, RAMC, and worked as an orderly at the Beaufort War Hospital, Bristol, a large Victorian gothic building that had been a lunatic asylum.[9] After thirteen months at Beaufort, the RAMC transferred Spencer to overseas duties. He left Beaufort in May 1916 and after ten weeks' training at Tweseldown Camp in Hampshire, the 24-year-old Spencer was sent to Macedonia, with the 68th Field Ambulance unit.[10] In 1917 he subsequently volunteered to be transferred to an infantry unit, the 7th Battalion, the Berkshire Regiment. In all, Spencer spent two and a half years on the front line in Macedonia, facing both German and Bulgarian troops, before he was invalided out of the Army following persistent bouts of malaria.[10] His survival of the war that killed so many of his fellows, including his elder brother Sydney,[11] who died in action in September 1918, indelibly marked Spencer's attitude to life and death. Such preoccupations came through time and again in his subsequent works.

Spencer returned to England at the end of 1918 and went back to his parents at Fernlea in Cookham, where he completed Swan Upping, the painting he had left unfinished when he enlisted.[12] Swan Upping was first exhibited at the New English Art Club in 1920 and was bought by J. L. Behrend. Spencer had begun the painting by making a small oil study and several drawings from memory before visiting Turks Boatyard beside Cookham Bridge to confirm his composition. Spencer worked systematically from top to bottom on the canvas but had only completed the top two-thirds of the picture when he had to leave it in 1915. Returning to the work Spencer found it difficult to continue after his war-time experiences, often stating "It is not proper or sensible to expect to paint after such experience."[13][14]

Travoys Arriving with Wounded ...

_(Art.IWM_ART_2268).jpg)

In 1919 Spencer was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee of the Ministry of Information to paint a large work for a proposed, but never built, Hall of Remembrance. The resulting painting, Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916, now in the Imperial War Museum, was clearly the consequence of Spencer's experience in the medical corps.[15] He wrote,

"About the middle of September 1916 the 22nd Division made an attack on Machine Gun Hill on the Doiran Vardar Sector and held it for a few nights. During these nights the wounded passed through the dressing stations in a never-ending stream."

Among the dressing stations was an old Greek church which Spencer drew such that, with the animal and human onlookers surrounding it, it would recall depictions of the birth of Christ, but to Spencer the wounded figures on the stretchers spoke of Christ on the Cross while the lifesaving work of the surgeons represented the Resurrection. He wrote,

"I meant it not a scene of horror but a scene of redemption." And also, "One would have thought that the scene was a sordid one...but I felt there was grandeur...all those wounded men were calm and at peace with everything, so the pain seemed a small thing with them."[16][17]

1920–1927

Spencer lived in Cookham until April 1920 when he moved to Bourne End to stay with the trade union lawyer Henry Slesser and his wife. While there, he worked on a series of paintings for their private oratory.[4] In all, during the year he spent at the Slessor's home, Spencer painted some twenty pictures including Christ Carrying the Cross, which is now in the Tate.[18][19] In 1921 Spencer stayed with Muirhead Bone at Steep in Hampshire where he worked on mural designs for a village hall war memorial scheme which was never completed.[20] In 1923 Spencer spent the summer in Poole, Dorset, with Henry Lamb. While there he worked on sketch designs for another possible war memorial scheme. These designs convinced two early patrons of Spencer's work, Louis and Mary Behrend, to commission a group of paintings as a memorial to Mary's brother, Lieutenant Henry Willoughby Sandham, who had died in the war. The Behrends planned to build a chapel in the village of Burghclere in Berkshire to house the paintings.

In October 1923, Spencer started renting Henry Lamb's studio in Hampstead where he began work on The Resurrection, Cookham. In 1925, Spencer married Hilda Carline, a former student at the Slade and the sister of the artists Richard and Sydney Carline. The couple first met in 1919 and had originally announced their engagement in 1922 after a Carline family painting trip to Yugoslavia.[21] Spencer repeatedly cancelled, or otherwise postponed, their wedding until 1925.[21] A daughter, Shirin, was born in November of that year and a second daughter, Unity, in 1930.

The Resurrection, Cookham

.jpg)

In February 1927 Spencer held his first one-man exhibition at the Goupil Gallery. The centre piece of the exhibition was The Resurrection, Cookham which received rave reviews in the British press. The Times' art critic described it as "the most important picture painted by any English artist in the present century. ... What makes it so astonishing is the combination in it of careful detail with the modern freedom of form. It is as if a Pre-Raphaelite had shaken hands with a Cubist."[22]

The huge painting is set in the grounds of the Holy Trinity Church, Cookham, and shows Spencer's friends and family from Cookham and Hampstead, and others emerging from graves watched by figures of God, Christ and the saints.[23] To the left of the church some of the resurrected are climbing over a stile, others are making their way to the river to board a Thames pleasure boat, others are simply inspecting their headstones.[24] Spencer created the picture in the early years of his marriage to Carline and she appears three times in the picture. Overall, the Goupil exhibition was a great success with thirty-nine of the displayed paintings being sold. The Resurrection, Cookham was purchased by Lord Duveen, who presented it to the Tate.[25] After the exhibition Spencer moved to Burghclere to begin work on the Sandham Memorial Chapel for the Behrends.

Burghclere, 1927–1932

The Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere was a colossal undertaking. Spencer's paintings cover a twenty-one foot high, seventeen-and-half foot wide end wall, eight seven foot high lunettes, each above a predella, with two twenty-eight feet long irregularly shaped strips between the lunettes and the ceiling. The Behrends were exceptionally generous patrons and not only paid for the Chapel to be built to Spencer's specifications but also paid the rent on the London studio where he completed The Resurrection, Cookham and built a house for him and Carline to live in nearby while working at Burghclere, as Spencer would be painting the canvases in situ.[26] The chapel was designed to Spencer's specifications by the architect Lionel Pearson and was modelled on Giotto's Arena Chapel in Padua.[27][28]

The sixteen paintings in the Chapel are double hung on opposite walls akin to the progression of altarpieces in a Renaissance church nave. The series begins with a lunette depicting shell-shocked troops arriving at the gates of Beaufort, continues with a scene of kit inspection at the RAMC Training Depot in Hampshire which is followed by scenes of Macedonia.[29][30] Spencer did not depict heroism and sacrifice, but rather in panels such as Scrubbing the Floor, Bedmaking, Filling Tea Urns and Sorting and Moving Kit Bags,[25] the unremarkable everyday facts of daily life in camp or hospital and a sense of human companionship rarely found in civilian life as he remembered events from Beaufort, Macedonia and Tweseldown Camp.[26][27] Such is the absence of violence in the panels, The Dugout panel was based on Spencer's thought of "how marvellous it would be if one morning, when we came out of our dug-outs, we found that somehow everything was peace and the war was no more."[22] The scene, Map Reading offers a contrast to the dark earth of the hospital and military camps in the other panels and shows a company of soldiers resting by a roadside paying little attention to the only officer depicted among the hundreds of figures Spencer painted for the Chapel. Bilberry bushes fill the background of the painting, making the scene appear green and Arcadian which seems to prefigure the paradise promised in the Resurrection of the Soldiers on the end, alter, wall.[14] Spencer imagined the Resurrection of the Soldiers taking place outside the walled village of Kalinova in Macedonia with soldiers rising out of their graves and handing in identical white crosses to a Christ figure towards the top of the wall.[23] Working on the Memorial Chapel has been described as a six-year process of remembrance and exorcism for Spencer[14] and he explained the emphasis on the colossal resurrection scene, "I had buried so many people and saw so many bodies that I felt death could not be the end of everything."[26]

While working at Burghclere, Spencer also undertook other small commissions including a series of five paintings, on the theme of Industry and Peace, for the Empire Marketing Board in 1929, which were not used, and a series of 24 pen-and-ink sketches for a 1927 Almanack.[7][20] Much later in his life Spencer adapted seven of these sketches into paintings including The Dustbin, Cookham painted in 1958.[2]

Cookham, 1932–1935

By 1932 Spencer was back in Cookham with his two daughters and Carline living in a large house, Lindworth, off the High Street.[3] Here Spencer painted observational studies of his surroundings and other landscapes, which would become the major themes of his work over the following years. During 1932 he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy and exhibited ten works at the Venice Biennale. However he was becoming dissatisfied with married life. Carline was often in Hampstead as her elder brother was badly ill and when she was in Cookham life with her was not the cosy domestic idyll Spencer expected. In 1929 Spencer had met the artist Patricia Preece, and he soon became infatuated with her. Preece was a young fashion-conscious artist who had lived in Cookham since 1927 with her lesbian partner, the artist Dorothy Hepworth.[8] In 1933 she first modelled for Spencer and when he visited Switzerland that summer, to paint landscapes, Preece joined him there.

The Church-House project

During the First World War Spencer had begun to conceive of a chapel of peace and love in which to display his works and these ideas developed further while working at Burghclere. Eventually he developed a complete scheme of domestic and religious spaces mixing his love of Cookham with cycles of paintings illustrating sacred and profane love. The original lay-out of the Church-House would have mirrored the geography of Cookham with the nave based on the High Street, while School Lane and the path beside the Thames would be the aisles.[7] In one version, Spencer envisaged the building would include bedrooms as chapels, fireplaces as altars and decorated bathrooms and lavatories while other versions of the scheme were more like an English parish church.[8] As well as a chapel dedicated to Carline, there would be a chapel dedicated to Elise Munday, the Spencer family servant, and the subject of Carline 's finest painting. Spencer had at least two significant affairs during his life, one with Daphne Charlton while at Leonard Stanley, and the other with Charlotte Murray, a Jungian analyst, when he was in Glasgow,[31] and there were to be chapels dedicated to both of them. Although the structure was never built, Spencer continually returned to the project throughout his life and continued to paint works for the building long after it had become clear it would never be constructed. His original scheme included three sequences of paintings, two of which The Marriage of Cana and The Baptism of Christ were completed. The Turkish Windows,(1934), and Love Among the Nations,(1935), were designed as long friezes for the nave of the Church-House.

Numerous other paintings were intended for the Church-House. These included the two paintings Spencer submitted for the 1935 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, Saint Francis and the Birds and The Dustman or The Lovers.[8] The Royal Academy rejected both pictures, and Spencer resigned from the Academy in protest. The rejection of the Saint Francis picture was particularly galling for Spencer as the model for the figure of Saint Francis had been his own father, wearing his own dressing gown and slippers,[32] which Spencer had intended to hang in the nave of the Church-House.[8]

Divorce and remarriage, 1935–1938

Spencer made a return visit to Switzerland in 1935, and Patricia Preece travelled with him. When they returned to Cookham, Spencer's wife, Carline, moved to Hampstead, and his contact with his daughters became limited. Carline was growing increasingly despondent and hurt at Spencer's fixation with Preece. She sent their older daughter Shirin to live with a relative. Shirin later commented: "When I was young I just thought this is how things were. But as I got older, and realised what Patricia had done, she became the one person I really hated."[33] Preece began to manage Spencer's finances and he later signed the deeds of his house, Lindworth, over to her. Between the middle of 1935 and 1936 Spencer painted a series of nine pictures, known as the Domestic Scenes in which he recalled, or re-imagined, life with Carline at home. While Spencer was painting these, Carline, as shown by her letters from the time,[34] finally started divorce proceedings and a decree absolute was issued in May 1937.

A week later Spencer married Preece; she, however, continued to live with Hepworth, and refused to consummate the marriage.[35] When Spencer's bizarre relationship with Preece finally fell apart, she refused to grant him a divorce. Spencer would often visit Carline, and he continued to do so throughout her subsequent mental breakdown and until her death from cancer in November 1950.[36] The painful intricacies of this three-way relationship became the subject in 1996 of a play, Stanley by the feminist playwright Pam Gems.

Spencer painted naked portraits of Preece in 1935 and 1936 and, also in 1936, a double nude portrait of himself and Preece, Self-Portrait with Patricia Preece, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum. This was followed, in 1937, by Double Nude Portrait: The Artist and His Second Wife, known as the Leg of mutton nude, a painting never publicly exhibited during Spencer's lifetime. In a futile attempt to be reconciled with Carline, Spencer went to stay with her in Hampstead for ten days. Her rejection of this approach is the basis of Hilda, Unity and Dolls, which Spencer painted during that visit.[37] During the winter of 1937, alone in Southwold, Suffolk, Spencer begin a series of paintings, The Beatitudes of Love, about ill-matched couples. These pictures, and others of often radical sexual imagery, were intended for cubicles in the Church-House where the visitor could "meditate on the sanctity and beauty of sex". When Sir Edward Marsh, Spencer's early patron, was shown these paintings his response was "Terrible, terrible Stanley!".[8]

In October 1938 Spencer had to leave Cookham and moved to London, spending six weeks with John Rothenstein before moving to a bedsit in Swiss Cottage. There was now no realistic hope of reconciliation with Carline and he was already distanced from Preece, who had rented out Lindworth so effectively evicting Spencer. At this low point Spencer painted four of the canvases in the Christ in the Wilderness series. He originally intended to paint a series of 40, one representing each day of Jesus's sojourn in the wilderness, but in the end only eight were completed and a ninth was left unfinished. By September 1939, he was staying at Leonard Stanley in Gloucestershire with the artists George and Daphne Charlton. Spencer created many important works in his room above the bar of the White Hart Inn which he used as a studio, including Us in Gloucestershire and The Wool Shop.[38] While in Gloucestershire, Spencer also began a series of over 100 pencil works, now known as the Scrapbook Drawings, which he continued to add to for at least ten years.

Port Glasgow, 1939–1945

Since late in 1938, Spencer's agent, Dudley Tooth had been managing Spencer's finances and when the Second World War broke out he wrote to E.M.O'R. Dickey, the secretary of the War Artists' Advisory Committee, WAAC, seeking employment for Spencer. In May 1940 WAAC sent Spencer to the Lithgows Shipyard in Port Glasgow on the River Clyde to depict the civilians at work there. Spencer became fascinated by what he saw and sent WAAC proposals for a scheme involving up to sixty-four canvases displayed on all four sides of a room.[39] WAAC agreed to a more modest series of up to eleven canvases, some of which would be up to six metres long. The first two of these, Burners and Caulkers were completed by the end of August 1940. WAAC purchased the three parts of Burners, but not Caulkers, for £300 and requested a further painting, Welders, for balance. Spencer delivered Welders in March 1941 and in May 1941 saw the two paintings hanging together for the first time at the WAAC exhibition in the National Gallery. WAAC held Spencer in the highest regard, and in particular Dickey ensured he received, almost, all the expenses and materials he requested and even accepted his refusal to fill-in any forms or sign a contract.[40]

_(1943)_(Art.IWM_ART_LD_3106).jpg)

_(1943)_(Art.IWM_ART_LD_3106).jpg)

_(1943)_(Art.IWM_ART_LD_3106).jpg)

Between trips to Port Glasgow, Spencer was renting a room in Epsom, to be near Carline and his children, but the landlady there disliked him and he wanted to move back to Cookham and work on the paintings in his old studio but he could not afford to rent it from Preece, so WAAC agreed further financial help for that purpose. In May 1942, Spencer delivered Template, followed by twelve portraits of Clydesiders in October 1942.[41] By June 1943 Spencer was having problems with the composition of the next painting in the series, Bending the Keel plate and considered abandoning it. Although he was not entirely happy with the painting, WAAC purchased it in October 1943 for 150 guineas.[42] About this time, the owner of the shipyard, James Lithgow, complained to WAAC about Spencer's portrayal of his shipyard. WAAC duly commissioned Henry Rushbury to go to Port Glasgow and produce some rather more conventional views of shipbuilding for Lithgow.[39] Spencer made further visits to Glasgow and by June 1944 had completed Riggers and begun work on Plumbers. After WAAC had purchased these two paintings, they did not have enough funds to authorise the completion of the entire original scheme of paintings. By the time WAAC was wound up, money had been made available for one further picture, The Furnaces, which would become the central piece of the scheme.[41] After the war, when the WAAC collection of artworks was dispersed to different museums, the complete Shipbuilding on the Clyde series was offered to the National Maritime Museum who refused to accept the pictures and they were given to the Imperial War Museum instead.[39]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

In November 2006, the Imperial War Museum asked Sir Alex Ferguson, whose father, brother and an uncle were working in the yards while Spencer was there, to lead a campaign to fund restoration of Spencer's paintings of the Port Glasgow's shipyards.[43]

The Riverside Museum, Glasgow, now displays Spencer's shipyard paintings as a biannual rotation of works on loan from the Imperial War Museum.[44] In 1982 sections from two of the eight panels were used as the artwork, on five different sleeves, for the single "Shipbuilding" by Robert Wyatt.[45] Four of the sleeves featured two different sections each from "Riggers" and "Riveters", which folded out into four-page leporello pictures.

In 2014 on the site of the former Kingston Shipyard in Port Glasgow, which is now a retail park, a memorial in plate steel was erected to Spencer.[46]

In 1945 Spencer returned to live in Cookham in a house called Cliveden View, which had once belonged to his brother Percy.[7]

Resurrection pictures, 1945–1950

While the Resurrection had long been a recurring theme in Spencer's work, in the years after the war it became especially so. Writing in his notebooks, Spencer attributed this to a revelation he had while in Port Glasgow working on the Shipbuilding on the Clyde series,

One evening in Port Glasgow when unable to write due to a jazz band playing in the drawing-room just below me, I walked up along the road past the gas works to where I saw a cemetery on a gently rising slope... I seemed then to see that it rose in the midst of a great plain and that all in the plain were resurrecting and moving towards it... I knew then that the resurrection would be directed from this hill.

Later he wrote,

I have read somewhere (might be Donne or Bunyan or Blake) that the resurrection is a kind of climbing of the Hill of Zion. I want to express this climbing idea... the hill will be illumined from the right, casting a long shadow across the plain far into the left side of the picture... Those resurrecting away in the plain on the left shadow-side of the hill must come round in front of the hill to join those coming from the right sunlit side, so there must be ground to walk on in front of the hill.[47]

Spencer's original plan for realising this vision would have required a canvas some fifty feet wide. Appreciating that this was impractical, he instead embarked on a series of paintings of various sizes.[48] The two largest of these, Resurrection: The Hill of Sion and Resurrection: Port Glasgow, at some twenty-two feet long each, matched the scale of his original vision.[23] These were supplemented by a series of triptychs, Reunion, Rejoicing, Waking Up and The Raising of Jairus' Daughter plus two smaller pieces.[47] A number of additional panels for some of the triptychs were planned but never completed. Spencer wanted the entire series displayed together, but each piece was sold to a different collector or gallery.[49] Resurrection: Port Glasgow was exhibited with the Shipbuilding on the Clyde series for the first time in 2000 to great acclaim.[50]

Final years

.jpg)

In 1950, the outgoing president of the Royal Academy, Sir Alfred Munnings, got hold of some of Spencer's Scrapbook Drawings and initiated a police prosecution against Spencer for obscenity.[35] It was reported in the press that the, unnamed, owner of the pictures agreed to destroy them. Spencer also appears to have removed some drawings from his private scrapbooks and continued to ensure that the Leg of mutton nude would not be exhibited during his lifetime. He was appointed a CBE and the new President of the Royal Academy, Sir Gerald Kelly, who had supported Spencer in the obscenity case, persuaded him to rejoin the Royal Academy, as an Associate before being elected an Academician.[7][35] Spencer visited his elder brother Harold in Northern Ireland in 1951, 1952 and 1953, painting portraits of Harold's daughter, Daphne, and urban scenes there, most notably Merville Garden Village near Belfast in 1951. In 1952 Spencer made a small number of lithographs on the theme of the Marriage at Cana which were published in a limited edition of thirty that year and reprinted in an edition of 70 after his death.[51]

In the spring of 1954, the Chinese government invited various western delegations to visit China for the fifth anniversary celebrations of the "Liberation" of October 1949.[52] Members of the hastily assembled "cultural delegation" included Stanley Spencer, Leonard Hawkes, Rex Warner, Hugh Casson and A. J. Ayer. Spencer told Zhou Enlai that "I feel at home in China because I feel that Cookham is somewhere near, only just around the corner." Towards the end of 1955, a large retrospective of Spencer's work was held at the Tate and he began a series of large paintings centred on the work Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta, which were intended for the Church-House.[6]

In his later years Spencer was seen as a "small man with twinkling eyes and shaggy grey hair, often wearing his pyjamas under his suit if it was cold." Spencer became a "familiar sight, wandering the lanes of Cookham pushing the old pram in which he carried his canvas and easel." A scene of Spencer pushing his easel along in a pram, and surrounded by angels, was the subject of the painting Homage to Spencer by the artist Derek Clarke.[53] The pram, black and battered, has survived to become an exhibit in the Stanley Spencer Gallery in Cookham, which is dedicated to Spencer's life and works.[3]

In 1958 Spencer painted The Crucifixion which was set in Cookham High Street and first displayed in Cookham Church. The painting employed a similar composition and viewpoint to an earlier painting, The Scarecrow, Cookham (1934) but with the two gargoyle-like carpenters nailing Christ to the cross and a screaming crucified thief, was by far the most violent of all Spencer's paintings. Spencer was made an Honorary Doctor of Letters by Southampton University in 1958, three days before he received his knighthood at Buckingham Palace.[12]

In December 1958 Spencer was diagnosed with cancer. He underwent an operation at the Canadian Red Cross Memorial Hospital on the Cliveden estate in 1959. After his operation, he went to stay with friends in Dewsbury. There, over five days from July 12 to July 16 he painted a final self-portrait. Self-Portrait (1959) shows a fierce, almost defiant individual. Lord Astor made arrangements so that Spencer could move into his childhood home, Fernlea, and he died of cancer at the Canadian Red Cross Memorial Hospital in December that year. At the time of his death Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta remained unfinished at his home.[4] Spencer was cremated and his ashes laid in Cookham churchyard, beside the path through to Bellrope Meadow. A discreet stone memorial marks the spot. The commemorative wording is: "To the memory of Stanley Spencer Kt. CBE RA, 1891–1959, and his wife Hilda, buried in Cookham cemetery 1950. Everyone that loveth is born of God and knoweth God: He that loveth not knoweth not God, for God is love."

Art market

The value of Spencer's paintings soared after a retrospective exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1980. The Resurrection; waking up fetched £770,000 at Christie's early in 1990, and in May of that year his Crucifixion (1958) fetched £1,320,000. "It was an all-time record for a modern British painting, and would have astounded Stanley, who was poor for so long."[54] On 6 June 2011 Sunflower and Dog Worship sold for £5.4m, beating a record of £4.7m set a few minutes earlier for Workmen in the House.[55]

Archives

In 1973 the Tate acquired a large proportion of the Spencer family archives. These included Spencer's notebooks, sketchbooks and correspondence including the weekly letters he wrote to his sister Florence, while he was stationed in Salonika during the First World War. Spencer was a prolific writer of lists and the archive contains several that offer insights to specific paintings plus other material such as lists of rooms for the Church-House project, lists of plants in his own paintings and even a list of the jewellery he bought for Patrica Preece.[56][57] Other correspondence by Spencer, some of which also dates from the First World War, is held in the archives of the Stanley Spencer Gallery in Cookham.[58] Tate Britain holds the largest collection of Spencer works in the world, but the largest collection on display at any one time is at the Stanley Spencer Gallery.[59]

Exhibitions

Exhibitions of his work held during Spencer's life included:

- 1927: Goupil Gallery,

- 1932: Venice Biennale,

- 1936: Tooth's Gallery, Bond Street,

- 1938: Venice Biennale,

- 1939: Leger Gallery,

- 1947: Retrospective at Temple Newsam House, Leeds,

- 1954: Arts Council exhibition,

- 1955: Tate retrospective,

- 1958: Exhibition at Cookham church and vicarage.

Posthumous exhibitions:

- 1980: Royal Academy

- 1981: Spencer in the Shipyard, Arts Council touring exhibition[60]

- 1997: Stanley Spencer: An English Vision, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C, then on tour to Mexico City and California,

- 2000: Men of the Clyde:Stanley Spencer's Vision at Port Glasgow, Scottish National Portrait Gallery[53]

- 2001: Tate Britain retrospective, then on tour to the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Ulster Museum,[31]

- 2002: Love, Desire, Faith, Abbothall Gallery, Kendel,[61]

- 2008: Laing Art Gallery,[62]

- 2009: York Art Gallery [63]

- 2009: Sargent, Sickert & Spencer, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge,[64]

- 2011: Stanley Spencer And The English Garden, Compton Verney House,[65]

- 2013: Heaven in a Hell of War, Somerset House,[66]

- 2013-14: Stanley Spencer in Cookham, Stanley Spencer Gallery,[67]

- 2014: Paradise Regained, Stanley Spencer Gallery

- 2015: The Creative Genius of Stanley Spencer, Stanley Spencer Gallery

- 2016: Stanley Spencer: Of Angels & Dirt, The Hepworth Wakefield,[68]

- 2016: Stanley Spencer: a twentieth century British Master, Carrick Hill, Adelaide, Australia[69]

References

- Frances Spalding (1990). 20th Century Painters and Sculptors. Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 1 85149 106 6.

- MaryAnne Stevens (1988). The Edwardians And After, The Royal Academy 1900–1950. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Stanley Spencer Gallery. "Stanley Spencer – A Short Biography". Stanley Spencer Gallery. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- David Boyd Haycock (2009). A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War. Old Street Publishing (London). ISBN 978-1-905847-84-6.

- Ysanne Holt (2003). British Artists and the Modernist Landscape. Aldershot, Hants.: Ashgate Publishing. p. 131. ISBN 0-7546-0073-4.

- Fiona MacCarthy (11 August 2007). "What ho, Giotto!". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Timothy Hyman and Patrick Wright (Editors) (2001). Stanley Spencer. Tate Gallery Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85437-377-3.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Fiona MacCarthy (1997). Stanley Spencer: An English Vision. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07337-2.

- "Glenside museum hosts a Stanley Spencer tour". University of the West of England. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- Paul Gough (2011). Your Loving Friend, Stanley. Sansom & Company. ISBN 978-1-906593-76-6.

- "Person Details SPENCER, Sydney". For King and Country. RBWM. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- David Nash Ford. "Sir Stanley Spencer 1891–1959". Royal Berkshire History. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Penelope Curtis (Editor). Tate Britain Companion, A Guide to British Art. Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84976-033-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Stephen Farthing (Editor) (2006). 1001 Paintings You Must See Before You Die. Cassell Illustrated/Quintessence. ISBN 978-1-84403-563-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Sir Peter Bazalgette (24 February 2016). "Artwork in focus: Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916". Art UK. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- Imperial War Museum. "Travoys arriving with Wounded at a dressing station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Art from the First World War. Imperial War Museum. 2008. ISBN 978-1-904897-98-9.

- "Sir Stanley Spencer, R.A., Carrying Matresses". Sotheby's. 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Tate. "Catalogue entry:Christ Carrying the Cross". Tate. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Andrew Causey (2014). Stanley Spencer Art as a Mirror of Himself. Lund Humphries. ISBN 978-1-84822-146-8.

- Alfred Hickling (24 February 1999). "Never marry an artist". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Ian Chilvers (Editor) (1988). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860476-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Victoria Ibbett (28 March 2016). "The theme of resurrection in Stanley Spencer's work". Art UK. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Tate. "Catalogue entry: The Resurrection, Cookham". Tate. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Keith Bell (1993). Stanley Spencer: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings. Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-8109-3836-7.

- Kitty Hauser (2001). Stanley Spencer (British Artists series). Tate Publishing. ISBN 1-85437-351-X.

- Adrian Tinniswood (forewood by) (2007). Treasures from the National Trust. National Trust Books. ISBN 978 19054 0045 4.

- Claudia Pritchard (3 November 2013). "Lest we forget those who scrubbed floors: Inside Stanley Spencer's unique war memorial". The Independent. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Richard Dorment (10 December 2013). "Stanley Spencer, at Somerset House, review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- Paul Gough (2006). Stanley Spencer: Journey to Burghclere. Sansom and Company (Bristol). ISBN 1-904537-46-4.

- Tom Rosenthal (9 April 2001). "Stan the Man". New Statesman. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- Adam Butler, Claire Van Cleave & Susan Stirling (Contributors) (1994). The Art Book. Phaidon Press. ISBN 978 0 7148 44879.

- Michael Hodges (4 February 2018). "Why Stanley Spencer tore apart his family for a lesbian muse". Radio Times.

- John Rothenstein (1979). Stanley Spencer, the Man: Correspondence and Reminiscences. Athens: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-0431-8.

- Tom Rosenthal (2 March 1998). "Visions on the up train". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Sir Stanley Spencer Stands Alone". BBC World Service. 14 July 2001. Retrieved 14 September 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Martin Gayford. "'We could have been happy'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- Stonehouse History Group (2011). "Stanley Spencer". Stonehouse History Group. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Brain Foss (2007). War paint: Art, War, State and Identity in Britain, 1939–1945. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10890-3.

- Imperial War Museum. "War artists archive, Stanley Spencer 1939–1941". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Imperial War Museum. "War artists archive, Stanley Spencer 1942–1950". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Imperial War Museum. "Search the collection:Bending the Keel Plate". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- Richard Brooks (19 November 2006). "Alex Ferguson leads battle to save war art". The Times. London. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- Glasgow Life. "What's on in Glasgow Life – Shipbuilding on the Clyde by Stanley Spencer". Glasgow Life. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Cook, Richard (4 June 1983). "When the Boat Comes in". NME. London, England: IPC Media: 6–7.

- Inverclyde Tourist Group. "Port Glasgow - Memorials". Inverclyde Tourist Group. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- R H Wilenski (1951). Stanley Spencer Resurrection Pictures (1945–1950). Faber And Faber / The Faber Gallery.

- Tate. "Catalogue entry, The Resurrection:Port Glasgow". Tate. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Elizabeth Rothenstein (1971). "Stanley Spencer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online). Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- Laura Cumming (13 August 2000). "Spencer's oxyacetylene angels". The Observer. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- Robin Garton (1992). British Printmakers 1855-1955 A Century of Printmaking from the Etching Revival to St Ives. Garton & Co / Scolar Press. ISBN 0 85967 968 3.

- Patrick Wright. (30 October 2010). "China: Behind the bamboo curtain". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Duncan Macmillan (8 March 2014). "Derek Clarke 1912–2014 (Obituary)". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- Robin Bootle & Valerie Bootle (1990). The Story of Cookham. Publications Committee of the Church of the Holy Trinity, Cookham, Berkshire. p. 53.

- "Stanley Spencer painting sells for £5.4m". BBC News. 16 June 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Adrian Glew (2001). Stanley Spencer Letters and Writings. Tate Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85437-350-1.

- Adrian Glew (2 September 2010). "Tate Archive 40; 1975 Stanley Spencer Home Service". The Tate. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Stanley Spencer Gallery. "Our Archive". Stanley Spencer Gallery. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Stanley Spencer Gallery. "Spencer Paintings in Public Art Galleries & Museums". Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Exhibition catalogue (1981). Spencer in the Shipyard. Arts Council of Great Britain. ISBN 0-7287-0277-0.

- Abbothall (2002). "Love, Desire, Faith". Abbothall Gallery. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- Tamzin Lewis (28 October 2008). "Stanley Spencer exhibition". The Journal. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- York Art Gallery (2009). "Special Exhibitions". York Art Gallery. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Jane Munro (2009). Sargent, Sickert & Spencer. The Fitzwilliam Museum. ISBN 0 904454 89 4.

- Adrian Hamilton (1 August 2011). "Stanley Spencer:This green and pleasant land". The Independent. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Brian Sewell (5 December 2013). "Stanley Spencer:Heaven in a Hell of War – exhibition review". The London Evening Standard. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- The Stanley Spencer Gallery (2013). "Stanley Spencer in Cookham". Stanley Spencer Gallery. Stanley Spencer Winter Exhibition. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- The Hepworth Wakefield (2016). "Stanley Spencer: Of Angels & Dirt". The Hepworth Wakefield. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Carrick Hill (2016). "Stanley Spencer: a twentieth century British Master". Carrick Hill. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

Further reading

- Anthony d'Offay (Firm), Stanley Spencer, and Hilda Spencer. Stanley Spencer and Hilda Carline. London: Anthony d'Offay, 1978.

- Art: Stanley Spencer, Eccentric. Newsweek. 130, no. 20: 92. 1997

- Paul Gough. A Terrible Beauty’: British Artists in the First World War. Bristol: Sansom and Company, 2010. ISBN 1-906593-00-0

- David Boyd Haycock. A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War. London: Old Street Publishing, 2009.

- Kitty Hauser. Stanley Spencer. British artists. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-691-09024-6

- Kenneth Pople. Stanley Spencer: A Biography. London: Collins, 1991. ISBN 0-00-215320-3

- Duncan Robinson. Stanley Spencer. Oxford: Phaidon, 1990. ISBN 0-7148-2616-2

- Rosemary Shepherd. Stanley Spencer and Women. [S.l.]: Ardent Art Publications, 2001.

- Gilbert Spencer. Stanley Spencer, by his brother Gilbert – Illustrated by the author. London : Victor Gollancz, 1961.

- A Guided Walk Round Stanley Spencer's Cookham. Estate of Stanley Spencer,1994.

- Gilbert and Stanley Spencer in Cookham: An Exhibition at the Stanley Spencer Gallery, Cookham 14 May – 31 August 1988. Cookham: Stanley Spencer Gallery, 1988.

- Alison Thomas and Timothy Wilcox. The Art of Hilda Carline: Mrs. Stanley Spencer. London: Usher Gallery, 1999. ISBN 0-85331-776-3

- Patrick Wright, Passport to Peking: a Very British Mission to China, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-954193-5

External links

- 193 paintings by or after Stanley Spencer at the Art UK site

- Sandham Memorial Chapel (National Trust)

- Art and Vision of Stanley Spencer

- Discussion of Spencer's Miss Ashwanden in Cookham by Janina Ramirez and Robin Ince: Art Detective Podcast, 03 May 2017