Standard step method

The standard step method (STM) is a computational technique utilized to estimate one-dimensional surface water profiles in open channels with gradually varied flow under steady state conditions. It uses a combination of the energy, momentum, and continuity equations to determine water depth with a given a friction slope , channel slope , channel geometry, and also a given flow rate. In practice, this technique is widely used through the computer program HEC-RAS, developed by the US Army Corps of Engineers Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC).[1]

Open channel flow fundamentals

The energy equation used for open channel flow computations is a simplification of the Bernoulli Equation (See Bernoulli Principle), which takes into account pressure head, elevation head, and velocity head. (Note, energy and head are synonymous in Fluid Dynamics. See Pressure head for more details.) In open channels, it is assumed that changes in atmospheric pressure are negligible, therefore the “pressure head” term used in Bernoulli’s Equation is eliminated. The resulting energy equation is shown below:

- Equation 1

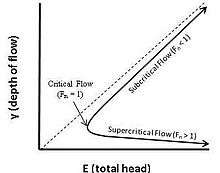

For a given flow rate and channel geometry, there is a relationship between flow depth and total energy. This is illustrated below in the plot of energy vs. flow depth, widely known as an E-y diagram. In this plot, the depth where the minimum energy occurs is known as the critical depth. Consequently, this depth corresponds to a Froude Number of 1. Depths greater than critical depth are considered “subcritical” and have a Froude Number less than 1, while depths less than critical depth are considered supercritical and have Froude Numbers greater than 1. (For more information, see Dimensionless Specific Energy Diagrams for Open Channel Flow.)

- Equation 2

Under steady state flow conditions (e.g. no flood wave), open channel flow can be subdivided into three types of flow: uniform flow, gradually varying flow, and rapidly varying flow. Uniform flow describes a situation where flow depth does not change with distance along the channel. This can only occur in a smooth channel that does not experience any changes in flow, channel geometry, roughness or channel slope. During uniform flow, the flow depth is known as normal depth (yn). This depth is analogous to the terminal velocity of an object in free fall, where gravity and frictional forces are in balance (Moglen, 2013).[3] Typically, this depth is calculated using the Manning formula. Gradually varied flow occurs when the change in flow depth per change in flow distance is very small. In this case, hydrostatic relationships developed for uniform flow still apply. Examples of this include the backwater behind an in-stream structure (e.g. dam, sluice gate, weir, etc.), when there is a constriction in the channel, and when there is a minor change in channel slope. Rapidly varied flow occurs when the change in flow depth per change in flow distance is significant. In this case, hydrostatics relationships are not appropriate for analytical solutions, and continuity of momentum must be employed. Examples of this include large changes in slope like a spillway, abrupt constriction/expansion of flow, or a hydraulic jump.

Water surface profiles (gradually varied flow)

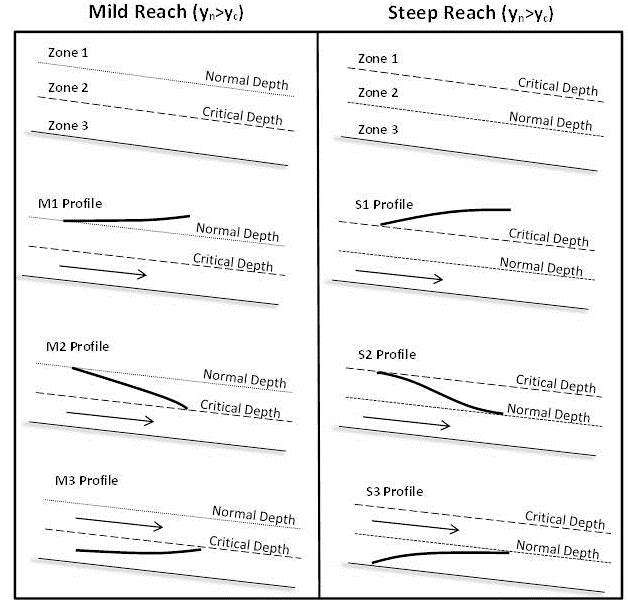

Typically, the STM is used to develop “surface water profiles,” or longitudinal representations of channel depth, for channels experiencing gradually varied flow. These transitions can be classified based on reach condition (mild or steep), and also the type of transition being made. Mild reaches occur where normal depth is subcritical (yn > yc) while steep reaches occur where normal depth is supercritical (yn<yc). The transitions are classified by zone. (See figure 3.)

Figure 3. This figure illustrates the different classes of surface water profiles experienced in steep and mild reaches during gradually varied flow conditions.[4] Note: The Steep Reach column should be labeled "Steep Reach (yn<yc).

The above surface water profiles are based on the governing equation for gradually varied flow (seen below)

- Equation 3

This equation (and associated surface water profiles) is based on the following assumptions:

- The slope is relatively small

- Channel cross-section is known at stations of interest

- There is a hydrostatic pressure distribution

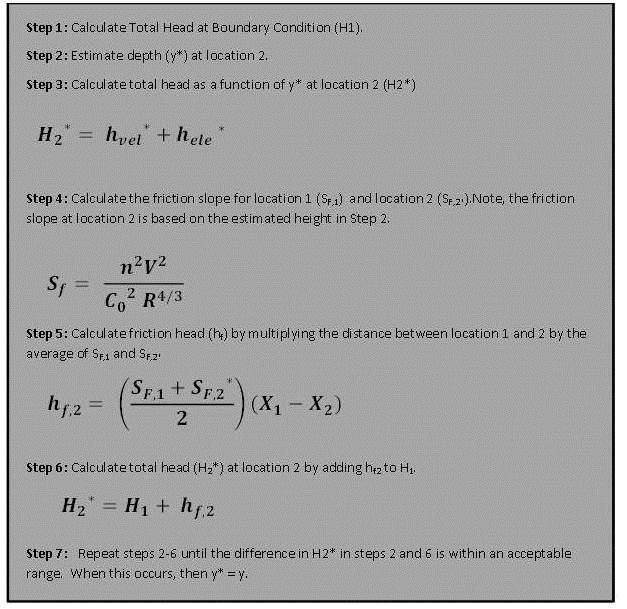

Standard step method calculation

The STM numerically solves equation 3 through an iterative process. This can be done using the bisection or Newton-Raphson Method, and is essentially solving for total head at a specified location using equations 4 and 5 by varying depth at the specified location.[5]

- Equation 4

- Equation 5

In order to use this technique, it is important to note you must have some understanding of the system you are modeling. For each gradually varied flow transition, you must know both boundary conditions and you must also calculate length of that transition. (e.g. For an M1 Profile, you must find the rise at the downstream boundary condition, the normal depth at the upstream boundary condition, and also the length of the transition.) To find the length of the gradually varied flow transitions, iterate the “step length”, instead of height, at the boundary condition height until equations 4 and 5 agree. (e.g. For an M1 Profile, position 1 would be the downstream condition and you would solve for position two where the height is equal to normal depth.)

Newton–Raphson numerical method

Computer programs like excel contain iteration or goal seek functions that can automatically calculate the actual depth instead of manual iteration.

Conceptual surface water profiles (sluice gate)

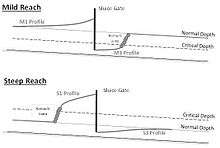

Figure 4 illustrates the different surface water profiles associated with a sluice gate on a mild reach (top) and a steep reach (bottom). Note, the sluice gate induces a choke in the system, causing a “backwater” profile just upstream of the gate. In the mild reach, the hydraulic jump occurs downstream of the gate, but in the steep reach, the hydraulic jump occurs upstream of the gate. It is important to note that the gradually varied flow equations and associated numerical methods (including the standard step method) cannot accurately model the dynamics of a hydraulic jump.[6] See the Hydraulic jumps in rectangular channels page for more information. Below, an example problem will use conceptual models to build a surface water profile using the STM.

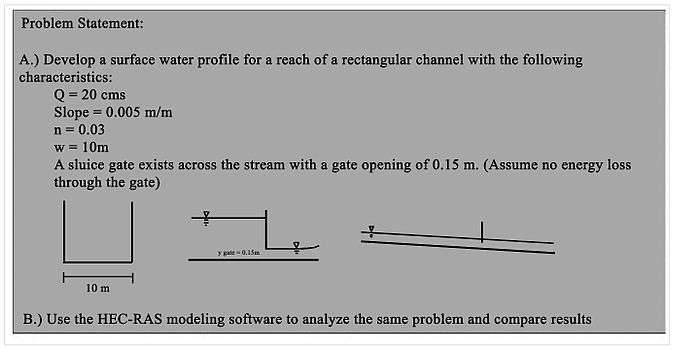

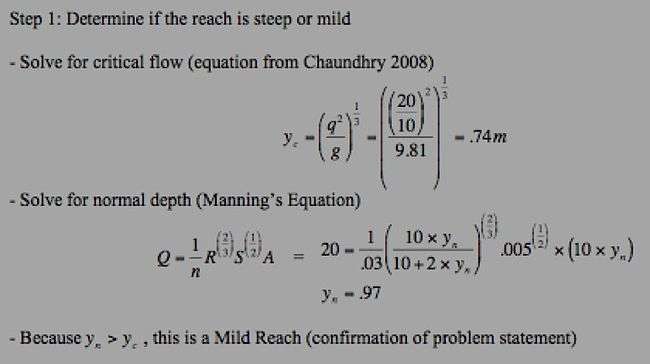

Example problem

Solution

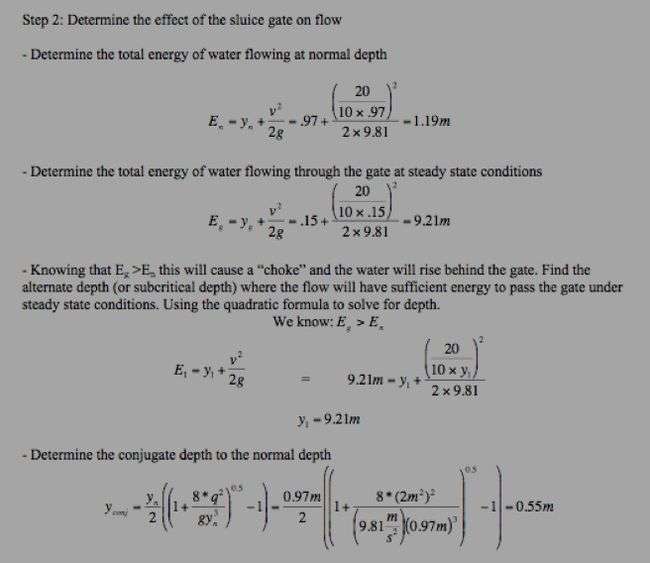

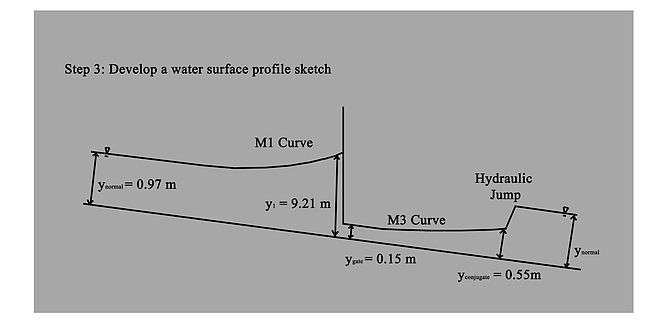

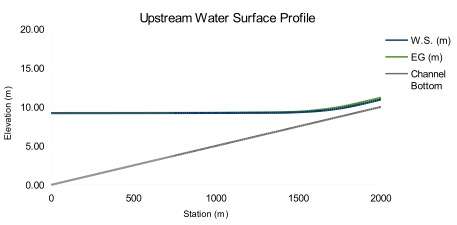

Using Figure 3 and knowledge of the upstream and downstream conditions and the depth values on either side of the gate, a general estimate of the profiles upstream and downstream of the gate can be generated. Upstream, the water surface must rise from a normal depth of 0.97 m to 9.21 m at the gate. The only way to do this on a mild reach is to follow an M1 profile. The same logic applies downstream to determine that the water surface follows an M3 profile from the gate until the depth reaches the conjugate depth of the normal depth at which point a hydraulic jump forms to raise the water surface to the normal depth.

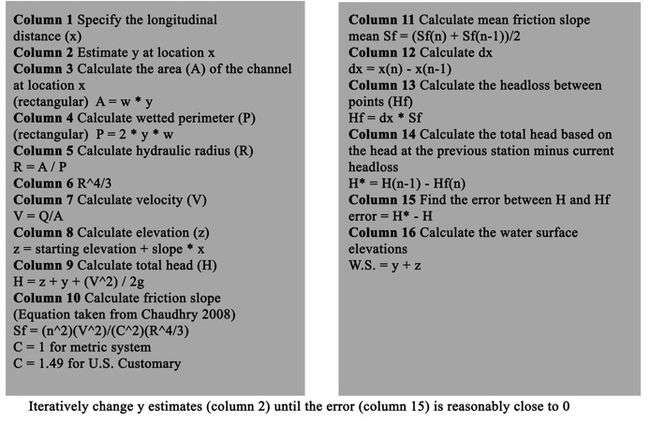

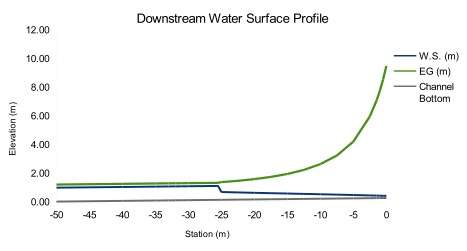

Step 4: Use the Newton Raphson Method to solve the M1 and M3 surface water profiles. The upstream and downstream portions must be modeled separately with an initial depth of 9.21 m for the upstream portion, and 0.15 m for the downstream portion. The downstream depth should only be modeled until it reaches the conjugate depth of the normal depth, at which point a hydraulic jump will form. The solution presented explains how to solve the problem in a spreadsheet, showing the calculations column by column. Within Excel, the goal seek function can be used to set column 15 to 0 by changing the depth estimate in column 2 instead of iterating manually.

Table 1: Spreadsheet of Newton Raphson Method of downstream water surface elevation calculations

Step 5: Combine the results from the different profiles and display.

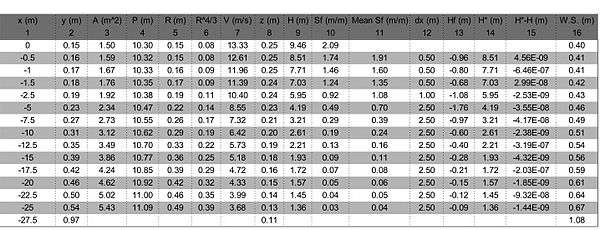

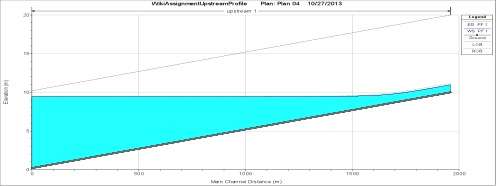

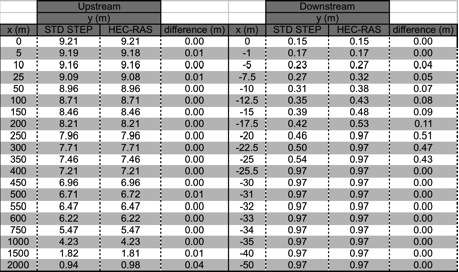

Normal depth was achieved at approximately 2,200 meters upstream of the gate.

Step 6: Solve the problem in the HEC-RAS Modeling Environment:

It is beyond the scope of this Wikipedia Page to explain the intricacies of operating HEC-RAS. For those interested in learning more, the HEC-RAS user’s manual is an excellent learning tool and the program is free to the public.

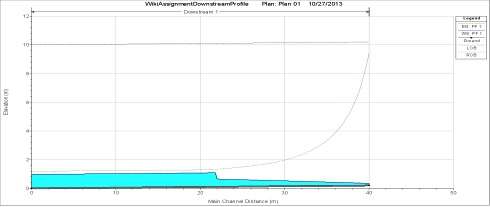

The first two figures below are the upstream and downstream water surface profiles modeled by HEC-RAS. There is also a table provided comparing the differences between the profiles estimated by the two different methods at different stations to show consistency between the two methods. While the two different methods modeled similar water surface shapes, the standard step method predicted that the flow would take a greater distance to reach normal depth upstream and downstream of the gate. This stretching is caused by the errors associated with assuming average gradients between two stations of interest during our calculations. Smaller dx values would reduce this error and produce more accurate surface profiles.

The HEC-RAS model calculated that the water backs up to a height of 9.21 meters at the upstream side of the sluice gate, which is the same as the manually calculated value. Normal depth was achieved at approximately 1,700 meters upstream of the gate.

HEC-RAS modeled the hydraulic jump to occur 18 meters downstream of the sluice gate.

References

- USACE. "HEC-RAS Version 4.1 User's Manual". Hydrologic Engineering Center, Davis, CA. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Chaudhry, M.H. (2008). Open-Channel Flow. New York: Springer.

- Moglen, G. "Lecture Notes from CEE 4324/5894: Open Channel Flow, Virginia Tech". Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Chow, V.T. (1959). Open-Channel Hydraulics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Chaudhry, M.H. (2008). Open-Channel Flow. New York: Springer.

- Chaudhry, M.H. (2008). Open-Channel Flow. New York: Springer.