Standard anatomical position

Because animals can change orientation with respect to their environment, and because appendages (arms, legs, tentacles, etc.) can change position with respect to the main body, it is important that anatomical terms of location refer to the organism when it is in its standard anatomical position.

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anatomical terminology |

|---|

| Bone |

| Location |

| Microanatomy |

| Motion |

| Muscle |

| Neuroanatomy |

Thus, all descriptions are with respect to the organism in its standard anatomical position, even when the organism in question has appendages in another position. However, a straight position is assumed when describing the proximo-distal axis. This helps avoid confusion in terminology when referring to the same organism in different postures.

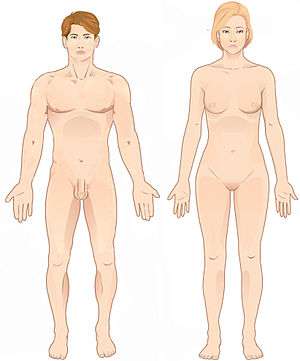

Human anatomy

Standard anatomical position is rigidly defined for human anatomy. In standard anatomical position, the human body is standing erect and at rest. Unlike the situation in other vertebrates, the limbs are placed in positions reminiscent of the supine position imposed on cadavers during autopsy. Therefore, the body has its feet together (or slightly separated), and its arms are rotated outward so that the palms are forward, and the thumbs are pointed away from the body (forearms supine). As well, the arms are usually moved slightly out from the body, so that the hands do not touch the sides.[1][2] The positions of the limbs (and the arms in particular) have important implications for directional terms in those appendages. The penis in the anatomical position is described in its erect position and therefore lies against the abdomen, hence the dorsal surface of the penis is actually anterior when the penis is pointing down between the legs.[3][4]

Skull

In humans, the anatomical position of the skull has been agreed by international convention to be the Frankfurt plane or Frankfort plane, a position in which the lower margins of the orbits, the orbitales, and the upper margins of the ear canals, the poria, all lie in the same horizontal plane. This is a good approximation to the position in which the skull would be if the subject were standing upright and facing forward normally.

In dogs, the skull is the more diverse within the species than any other mammal so the dorsal, ventral, and lateral views are the most important positions[5]

History

Frankfurt plane

The Frankfurt plane was established at the World Congress on Anthropology in Frankfurt am Main, Germany in 1884, and decreed as the anatomical position of the human skull. It was decided that a plane passing through the inferior margin of the left orbit (the point called the left orbitale) and the upper margin of each ear canal or external auditory meatus, a point called the porion, was most nearly parallel to the surface of the earth at the position the head is normally carried in the living subject.[6] The alternate spelling Frankfort plane is also widely used, and found in several medical dictionaries, although Frankfurt is the modern standard spelling of the city it is named for. Another name for the plane is the auriculo-orbital plane.

Note that in the normal subject, both orbitales and both porions lie in a single plane. However, due to pathology, this is not always the case. The formal definition specifies only the three points listed above, sufficient to describe a plane in three-dimensional space.

For purposes of comparison of human skulls with those of some other species, notably hominids and primates, the skulls may be studied in the Frankfurt plane; nonetheless, the Frankfurt plane is not considered to be the anatomical position for most non-primate species.

The Frankfurt plane may also be used as a reference point in related fields. For example, in prosthodontics, the Frankfurt-Mandibular plane Angle (FMA) is the angle formed at the intersection of the Frankfurt plane with the mandibular plane.

Other animals

Canines

For dogs, the standard anatomical position is having the abdomen ventral by each paw standing on the supporting surface.[7]

References

- Marieb, E.N. Human Anatomy and Physiology pub: Benjamin/Cummings, ISBN 0-8053-4281-8

- Tortora, G.J. and Derrickson, B. Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. Wiley 2006 ISBN 0-471-68934-3

- Faculty of Biological Science, University of Leeds: Introductory Anatomy http://www.leeds.ac.uk/chb/lectures/anatomy2.html

- Gunter, Dr. Jen (2019). The Vagina Bible. United States of America: Citadel Press. pp. 5, 393. ISBN 978-0-8065-3931-7.

- Evans, H.E., & Miller, M. E. Miller's anatomy of the dog, ISBN 978-143770812-7

- "PDF from National Center for Social Research explaining the Frankfurt Plane" (PDF).

- Evans, H.E., & Miller, M. E. Miller's anatomy of the dog, ISBN 978-143770812-7