St Beuno's Church, Trefdraeth

St Beuno's Church, Trefdraeth is the medieval parish church of Trefdraeth, a hamlet in Anglesey, north Wales. Although one 19th-century historian recorded that the first church on this location was reportedly established in about 616, no part of any 7th-century structure survives; the oldest parts of the present building date are from the 13th century. Alterations were made in subsequent centuries, but few of them during the 19th century, a time when many other churches in Anglesey were rebuilt or were restored.

| St Beuno's Church, Trefdraeth | |

|---|---|

View from the south, showing the transept and porch | |

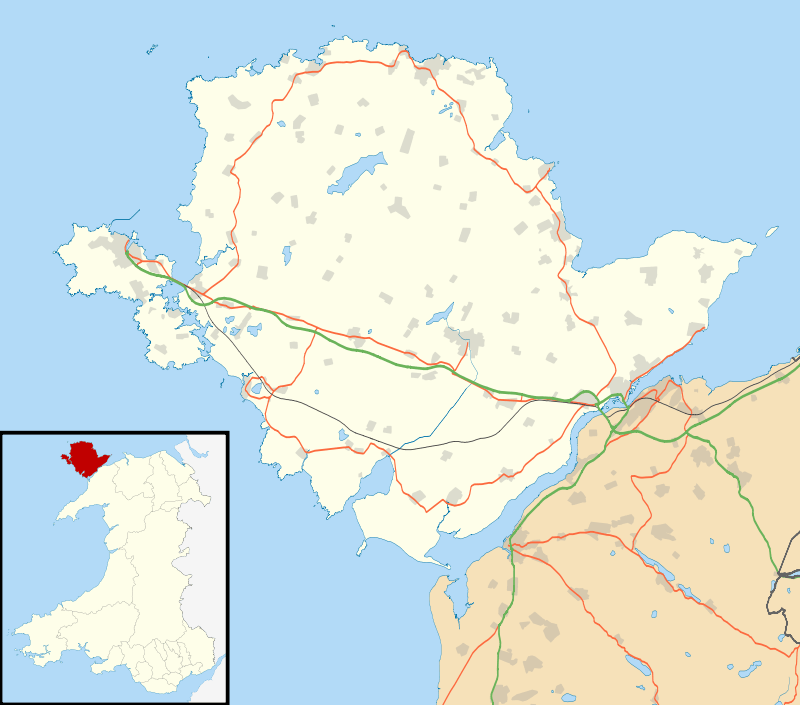

St Beuno's Church, Trefdraeth Location in Anglesey | |

| OS grid reference | SH408704 |

| Location | Trefdraeth, Anglesey |

| Country | Wales, UK |

| Denomination | Church in Wales |

| History | |

| Status | Church |

| Founded | First church reputedly established c. 616; earliest parts of present building 13th century |

| Dedication | St Beuno |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Designated | 30 January 1968 |

| Style | Decorated |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 59 feet (18 m) |

| Width | 15 feet (4.6 m) |

| Materials | Rubble masonry and squared stones; slate roof |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Trefdraeth with Aberffraw with Llangadwaladr with Cerrigceinwen |

| Deanery | Malltraeth |

| Archdeaconry | Bangor |

| Diocese | Diocese of Bangor |

| Province | Province of Wales |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | Vacant [1] |

St Beuno's is part of the Church in Wales, and its parish is one in a group of four. The church remains in use but as of 2013 there is no parish priest. It is a Grade II* listed building, a national designation for "particularly important buildings of more than special interest",[2] in particular because it is regarded as "an important example of a late Medieval rural church" with an unaltered simple design.[3]

History and location

St Beuno's Church is in Trefdraeth, a hamlet in the south-west of Anglesey by Malltraeth Marsh, about 5 miles (8 km) south-west of the county town of Llangefni. It stands in a roughly circular llan (Welsh for an enclosed piece of land, particularly around a church) north of the road between Trefdraeth and Bethel.[3][4][5] Beuno, a 7th-century Welsh saint, has several churches in north Wales dedicated to him.[6]

According to Angharad Llwyd (a 19th-century historian of Anglesey), the first church on this site was reportedly established in about 616.[7] No part of any 7th century building survives, and restoration over the years has removed much historical evidence for the church's development.[5]

The earliest parts of the present structure are the nave and the chancel, which are 13th-century. The church shows signs of alterations and additions in subsequent centuries. A transept or chapel was added to the south side of the chancel in the late 13th or early 14th century. The arch between them was once the archway between the chancel and the nave but was later moved. The bellcote at the west end of the roof was added in the 14th century. The porch on the south side of the nave was built in about 1500, and was re-roofed in 1725. A doorway in the north wall of the nave was inserted in the late 15th or early 16th century, and now leads into a vestry added in the 19th century. The main roof is largely 17th-century.[3] Some repairs were carried out in the 1840s, with further repairs in 1854 under the supervision of the diocesan architect, Henry Kennedy.[4]

Benefice

St Beuno's is one of four churches in the benefice of Trefdraeth with Aberffraw with Llangadwaladr with Cerrigceinwen. Other churches in the benefice include St Beuno's, Aberffraw and St Cadwaladr's, Llangadwaladr.[1] The church is in the Deanery of Malltraeth, the Archdeaconry of Bangor and the Diocese of Bangor.[8] As of 2013 the parishes have no incumbent priest.[1]

A number of notable clergy have held the living of St Beuno's. Henry Rowlands, Bishop of Bangor 1598–1616, was rector of Trefdraeth during his episcopacy, as the income from the parish was attached to the bishopric.[9] The scholar and rhetorician Henry Perry was appointed priest in 1606.[10] Griffith Williams was appointed rector in 1626 and went on to be Dean of Bangor in 1634.[11] David Lloyd was rector in the late 1630s and early 1640s, and thereafter Dean of St Asaph.[12] Robert Morgan was rector before and after the English Civil War and was made Bishop of Bangor in 1666.[13] John Pryce was rector 1880–1902 and Dean of Bangor 1902–1903.[14]

Welsh language controversy

In 1766 John Egerton, Bishop of Bangor, appointed an elderly English priest, Dr Thomas Bowles, to the parish of St Beuno, Trefdraeth and its chapelry of St Cwyfan, Llangwyfan. Between them the parish and chapelry had about 500 parishioners, of whom all but five spoke only Welsh, whereas Bowles spoke only English.[15][16] The parishioners and churchwardens of Trefdraeth petitioned against Bowles's appointment, arguing that the appointment of a priest who did not speak Welsh breached the Articles of Religion, the Act for the Translation of the Scriptures into Welsh 1563 and the Act of Uniformity 1662. In 1773 the Court of Arches ruled that only clergy who could speak Welsh should be appointed to Welsh-speaking parishes, and Bowles should not have been appointed, but he now held the ecclesiastical freehold of the benefice and the case to deprive him of it had not been proved.[15] The court therefore let Bowles stay in post, which he did until he died in November of that year.[15] Bowles was then replaced in the parish and chapelry with Richard Griffith, a priest who spoke Welsh.[15]

Architecture and fittings

St Beuno's is Decorated Gothic, built mainly with rubble masonry, with squared stones used to create courses in the nave's south wall and the lower part of the west wall. There are external buttresses at the west and east ends, the south porch and the south transept. The roof is surfaced with hexagonal slates and has a stone bellcote on its west gable. Internally, there is no structural division between the nave and the chancel save for a step up to the chancel.[3] The nave and chancel together are 59 feet (18 m) long and the church is 15 feet (4.6 m) wide.[5] Near the eastern end of the church is a transept or chapel on the south side of the chancel, from which it is separated by a step down and an arch.[3] The transept is 13 feet 9 inches (4.2 m) by 14 feet 6 inches (4.4 m).[5]

The windows range in age from the late 14th or early 15th century to the 19th century. The oldest is the chancel east window, which has an 18th-century inscribed slate slab as its sill. The window is a pointed arch with three lights (sections of window separated by mullions), and it has a stained glass of the Crucifixion of Jesus that was installed as a memorial in 1907. The nave north wall has a window from about 1500, which was originally in the nave south wall. The nave west window is rectangular, again from about 1500. In the nave south wall are two early 19th-century windows set in square frames, one single-light and one two-light. The transept has a 19th-century two-light arched window in its south wall, which contains the oldest stained glass in the church: 15th-century fragments of a crucifixion scene. It also has a pointed arched doorway in its west wall, from the late 13th or early 14th century.[3]

The church is entered through the porch to the west end of the south wall of the nave, which leads to an arched doorway. There are two 18th-century slate plaques on the walls by the south door commemorating those who made donations to the poor of the parish; one has names from 1761, the other from 1766. On the opposite wall, a 17th-century slate plaque commemorates Hugh ap Richard Lewis and his wife Jane (died 1660 and 1661 respectively). The internal timbers of the roof, some of which are old, are exposed, but there is a decorated panelled barrel-vaulted ceiling above the sanctuary at the east end of the church.[3][5] The transept roof is largely 17th-century.[5]

The cylindrical font is 12th-century, and is at the west end of the church. Four of its six panels are decorated with saltires; a fifth has a Celtic cross in knotwork with a ring; the sixth is blank.[4] One author has pointed out the similarities with the fonts of St Cristiolus's, Llangristiolus, which is about 2 miles (3 km) away, and of St Beuno's, Pistyll, in the nearby county of Gwynedd.[17]

A survey by the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire in 1937 also noted the early 18th-century communion rails, a plain oak communion table dated 1731, and a wooden font cover dated 1714. Other memorials, including parts of an early 14th-century inscribed slab, were also recorded. Three items of church silver were included in the survey: a cup (dated 1610–1611), a paten (1719) and a flagon (1743). Externally, an 18th-century brass sundial on a slate pedestal was noted, as was a weathered decorated stone on the lychgate, thought to be from the 10th century.[5] The Arts and Crafts Movement pulpit was made in 1920.[4]

Churchyard

The churchyard contains the Commonwealth war graves of a Royal Engineers soldier of World War I and a Pioneer Corps soldier of World War II.[18]

Assessment

The church has national recognition and statutory protection from alteration as it has been designated a Grade II* listed building – the second-highest of the three grades of listing, designating "particularly important buildings of more than special interest".[2] It was given this status on 30 January 1968, and has been listed because it is "an important example of a late Medieval rural church". Cadw (the Welsh Assembly Government body responsible for the built heritage of Wales and the inclusion of Welsh buildings on the statutory lists) also notes that the church's "simple design [remained] unaltered during the extensive programme of church re-building and restoration on Anglesey in the 19th century."[3]

In 1833 Angharad Llwyd described the church as "a small neat edifice", with "an east window of modern date and of good design".[7] She noted that the parish registers, legible from 1550 onwards, were the second oldest in north Wales.[7] Similarly, the 19th-century publisher Samuel Lewis said the church was a "small plain edifice" that could hold nearly 300 people.[19]

In 1846 the clergyman and antiquarian Harry Longueville Jones wrote that the church "has been lately repaired in a judicious manner, but without any restoration of importance being attempted, and is in good condition".[20] He added that with its "good condition this ranks as one of the better churches of the island."[20] The Welsh politician and church historian Sir Stephen Glynne visited the church in October 1849. He said that the chapel on the south side resembled several others in Anglesey and Caernarfonshire. He also noted the new slate roof, the "mostly open and plain" seats, and the "very large cemetery ... commanding an extensive view".[21]

A 2006 guide to the churches of Anglesey describes St Beuno's as being in "a pleasant and quiet rural location".[22] It adds that the church was "fairly small" and the roof had "unusual ornately-shaped slates".[22] A 2009 guide to the buildings of the region comments that "for once" Kennedy had repaired rather than replaced the church.[4] It notes that "strangely" the chancel arch had been reset in the transept, and says that the nave roof was of "unusual construction".[4]

See also

- St Beuno's Church, Penmorfa – a church near Porthmadog on a site said to have been used by Beuno

- St Beuno's church, Bettws Cedewain

References

- "Church in Wales: Benefices". Church in Wales. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- What is listing? (pdf). Cadw. 2005. p. 6. ISBN 1-85760-222-6.

- Cadw, "Church of St. Beuno (Eglwys Beuno Sant) (Grade II*) (5564)", National Historic Assets of Wales, retrieved 2 April 2019

- Haslam, Richard; Orbach, Julian; Voelcker, Adam (2009). "Anglesey". Gwynedd. The Buildings of Wales. Yale University Press. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-0-300-14169-6.

- Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire (1968) [1937]. "Trefdraeth". An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Anglesey. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 147.

- Lloyd, John Edward (2009). "Beuno". Welsh Biography Online. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Llwyd, Angharad (2007) [1833]. A History of the Island of Mona. Llansadwrn, Anglesey: Llyfrau Magma. p. 171. ISBN 1-872773-73-7.

- "Deanery of Malltraeth: St Beuno, Trefdraeth". Church in Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Roberts, Glyn (2009). "Henry Rowland". Welsh Biography Online. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Hughes, Garfield Hopkin (2009). "Henry Perri". Welsh Biography Online. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Roberts, Griffith Thomas (2009). "Griffith Williams". Welsh Biography Online. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Jones, John James (2009). "David Lloyd". Welsh Biography Online. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Dodd, Arthur Herbert (2009). "Robert Morgan". Welsh Biography Online. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Jenkins, Robert Thomas (2009). "John Pryce". Welsh Biography Online. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- The Cymmrodorion (1773). The Depositions, Arguments and Judgement in the Cause of the Church-Wardens of Trefdraeth, In the County of Anglesea, against Dr. Bowles; adjudged by the Worshipful G. Hay, L.L.D. Dean of the Arches: Instituted To Remedy the Grievance of preferring Persons Unacquainted with the British Language, to Livings in Wales. London: William Harris. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- Ellis, Peter Berresford (1994) [1993]. Celt and Saxon The Struggle for Britain AD 410–937. London: Constable & Co. pp. 241–242. ISBN 0-09-473260-4.

- Rees, Elizabeth (2003). An essential guide to Celtic sites and their saints. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-86012-318-7.

- CWGC Cemetery report, breakdown obtained from casualty record.

- Lewis, Samuel (1849). "Trêvdraeth (Trêf-Draeth)". A Topographical Dictionary of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Longueville Jones, Harry (July 1846). "Mona Mediaeva No. III". Archaeologia Cambrensis. Cambrian Archaeological Association. III: 297–298. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Glynne, Sir Stephen (1900). "Notes on the Older Churches of the Four Welsh Dioceses". Archaeologia Cambrensis. 5th. Cambrian Archaeological Association. XVII: 109. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Jones, Geraint I.L. (2006). Anglesey Churches. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. pp. 126–127. ISBN 1-84527-089-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Beuno's Church, Trefdraeth. |