Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita

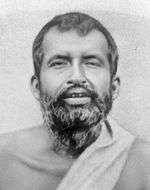

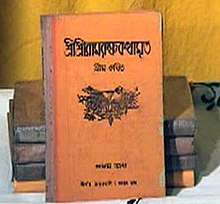

Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita (Bengali: শ্রীশ্রীরামকৃষ্ণ-কথামৃত, Śrī-Śrī-Rāmakṛṣṇa-Kathāmṛta, The Nectar of Sri Ramakrishna's Words) is a Bengali five-volume work by Mahendranath Gupta (1854–1932) which recounts conversations and activities of the 19th century Indian mystic Ramakrishna, and published consecutively in years 1902, 1904, 1908, 1910 and 1932. The Kathamrita is a regarded as a Bengali classic[1] and revered among the followers as a sacred scripture.[2] Its best-known translation into English is entitled The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (1942).

The 5 volumes of Kathamrita for display at Kathamrita Bhavan. | |

| Author | Mahendranath Gupta |

|---|---|

| Original title | শ্রীশ্রীরামকৃষ্ণ-কথামৃত |

| Country | India |

| Language | Bengali |

| Genre | Spirituality |

| Publisher | Kathamrita Bhavan |

Publication date | 1902, 1904, 1908, 1910 and 1932 |

Methodology and history

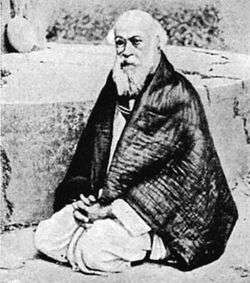

Mahendranath Gupta (famously known simply as "M.") was a professor at Ripon College and taught at a number of schools in Kolkata. He had an academic career at Hare School and Presidency College in Kolkata. M had the habit of maintaining a personal diary since the age of thirteen.[3] M met Ramakrishna in 1882 and attracted by Ramakrishna's teachings, M would maintain a stenographic record Ramakrishna's conversations and actions in his diary, which finally took the form of a book Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita.[2][4] Initially when M began writing the diaries, he had no plans of publication.[4][5] Regarding his methodology M wrote, "I wrote everything from memory after I returned home. Sometimes I had to keep awake the whole night...Sometimes I would keep on writing the events of one sitting for seven days, recollect the songs that were sung, and the order in which they were sung, and the samadhi and so on."[4] In each of his Kathamrita entries, M records the data, time and place of the conversation.[6] The title Kathamrita, literally "nectarine words" was inspired by verse 10.31.9 from the Vaishnava text, the Bhagavata Purana.[7]

The pre-history of the Kathamrita has been discussed in R.K.Dasputa's essay (Dasgupta 1986).[8] The first volume (1902) was preceded by a small booklet in English called A Leaf from the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (1897).[8] After the death of Ramakrishna, the growing public recognition would have encouraged Gupta to make his diary public. M thought that his was an important medium for public dissemination of Ramakrishna's ideas. M also sought Sarada Devi's appraisal before the publication of the dairy.[9] Between 1898 and 1902, transliterated excerpts from his diary were published in leading Bengali journals like Bangadarshan, Udbodhan, Hindu Patrika, Shaitya Patrika and Janmabhumi.[9] The first four volumes were published in 1902, 1904, 1908 and 1910 respectively and the fifth volume in 1932, delayed because of M's health problems.[10] At the time of M's death in 1932, he was contemplating at least six to seven volumes after which he hoped to rearrange the entire material chronologically.[6][10]

According to Sumit Sarkar,"The Kathamrita was published from 15 to 50 years after the sessions with Ramakrishna, and covers a total of only 186 days spread over the last four and a half years of the saint's life. The full text of the original diary has never been made publicly available. Considered as a constructed 'text' rather than simply as a more-or-less authentic 'source', the Kathamrita reveals the presence of certain fairly self-conscious authorial strategies...The high degree of 'truth effect' undeniably conveyed by the Kathamrita to 20th century readers is related to its display of testimonies to authenticity, careful listing of 'types of evidence', and meticulous references to exact dates and times."[11] Tyagananda and Vrajaprana write, "...at the time of M' death, he had enough diary material for another five or six volumes. Poignantly and frustratingly, M's diary notations were as sparse as they were cryptic. As a result, M's Kathamrita project ended with the fifth volume. And, lest there be any misunderstanding, it needs to be said that the sketchy notations which constitute the reminder of M's diary belong solely to M's descendants, not to the Ramakrishna Order. It also needs to be pointed out that, according to Dipak Gupta, M's great-grandson, scholars can, and have, seen these diaries."[6]

Contents

The Kathamrita contains the conversations of Ramakrishna from 19/26 February 1882 to 24 April 1886, during M's visits.[1] M—even with his partial reporting—offers information about a great variety of people with very different interests converging at Dakshineswar Kali temple including, "... childless widows, young school-boys (K1: 240, 291; K2: 30, 331; K3: 180, 185, 256), aged pensioners (K5: 69-70), Hindu scholars or religious figures (K2: 144, 303; K3: 104, 108, 120; K4: 80, 108, 155, 352), men betrayed by lovers (K1: 319), people with suicidal tendencies (K4: 274-275), small-time businessmen (K4: 244), and, of course, adolescents dreading the grind of samsaric life (K3: 167)."[12] The Kathamrita also records the devotional songs that were sung by Ramakrishna, including those of Ramprasad, an 18th-century Shakta poet.[13][14]

Translations

Several English translations exist; the most well-known is The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (1942), by Swami Nikhilananda of the Ramakrishna Order.[15] This translation has been criticized as inaccurate by Jeffrey Kripal, while others such as Lex Hixon and Swami Tyagananda have regarded the translation as authentic and culturally sensitive.

A translation by Sachindra Kumar Majumdar, entitled Conversations with Sri Ramakrishna, is published electronically by SRV Retreat Center, Greenville NY, following the original five-volume format of the Kathamrita.[16]

The latest complete translation, by Dharm Pal Gupta, is intended to be as close to the Bengali original as possible, conveyed by the words "Word by word translation" on the cover. All 5 volumes have been published.[17]

References and notes

- Sen 2001, p. 32

- Jackson 1994, pp. 16–17

- Sen 2001, p. 42

- Tyagananda & Vrajaprana 2010, pp. 7–8

- Sen 2001, p. 28

- Tyagananda & Vrajaprana 2010, pp. 12–14

- Tyagananda & Vrajaprana 2010, pp. 10

- Sen 2001, p. 27

- Sen 2001, pp. 29–31

- Sen 2001, pp. 46–47

- Sarkar 1993, p. 5

- Sen 2006, pp. 172–173

- Hixon 2002, pp. 16-17

- Harding 1998, p. 214

- Swami Nikhilananda (1942). The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. New York, Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center. OCLC 4577618

- "Sri Dharm Pal Gupta started the task of translating them into English maintaining the same spirit of faithful translation. And before he left this world in 1998, he had completed the colossal work of translating all the five parts of Kathamrita into English.", Publisher’s Note,Monday, 1 January 2001, http://www.kathamrita.org Archived 4 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Dasgupta, R.K (June 1986). Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita as a religious classic. Bulletin of the Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harding, Elizabeth U. (1998). Kali, the Dark Goddess of Dakshineswar. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1450-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hixon, Lex (2002). Great Swan: Meetings With Ramakrishna. Burdett, N.Y.: Larson Publications. ISBN 0-943914-80-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Carl T. (1994). Vedanta for the West. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33098-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gupta, Mahendranath; Dharm Pal Gupta (2001). Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita. Sri Ma Trust. ISBN 978-81-88343-00-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- D.P. Gupta; D.K. Sengupta, eds. (2004). Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita Centenary Memorial (PDF). Kolkata: Sri Ma Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011.

- Sarkar, Sumit (1993). An exploration of the Ramakrishna Vivekananda tradition. Indian Institute of Advanced Study.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sen, Amiya P. (June 2006). "Sri Ramakrishna, the Kathamrita and the Calcutta middle classes: an old problematic revisited". Postcolonial Studies. 9 (2): 165–177. doi:10.1080/13688790600657835.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sen, Amiya P. (2001). "Three essays on Sri Ramakrishna and his times". Indian Institute of Advanced Study. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Tyagananda; Vrajaprana (2010). Interpreting Ramakrishna: Kali's Child Revisited. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 410. ISBN 978-81-208-3499-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)