Sranan Tongo

Sranan Tongo (also Sranantongo "Surinamese tongue", Sranan, Taki Taki, Surinaams, Surinamese, Surinamese Creole)[4] is an English-based creole language that is spoken as a lingua franca by approximately 500,000 people in Suriname.[1]

| Sranan Tongo | |

|---|---|

| Sranan Tongo | |

| Native to | Suriname |

| Ethnicity | Surinamese |

Native speakers | (130,000 cited 1993)[1] L2 speakers: 50% of the population of Suriname (1993?)[2] |

English Creole

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | srn |

| ISO 639-3 | srn |

| Glottolog | sran1240[3] |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABB-aw |

Developed originally among slaves from West Africa and English colonists, its use as a lingua franca expanded after the Dutch took over the colony in 1667, and 85% of the vocabulary comes from Dutch. It became the common language also among the indigenous peoples and languages of contract workers imported by the Dutch, including speakers of Javanese, Sarnami Hindustani, Saramaccan, and varieties of Chinese. Sranan Tongo is widely spoken in Surinam and in places where its emigrants have settled, such as the Netherlands, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

Origins

The Sranan Tongo words for "to know" and "small children" are sabi and pikin (respectively derived from Portuguese saber and pequeno). The Portuguese were the first European explorers of the West African coast. A trading pidgin language developed between them and Africans, and later explorers, including the English, also used this creole.

Based on its lexicon, Sranan Tongo has been found to have developed as mostly an English-based creole language, because of the early influence of English colonists here, who imported numerous Africans as slaves for the plantations. After the Dutch takeover in 1667 (when they ceded New Netherland in North America to the English), a substantial overlay of words were adopted from the Dutch language.

Sranan Tongo's lexicon is a fusion of mostly English grammar[5] and Dutch vocabulary (~85%), plus some words from Portuguese and West African languages. It began as a pidgin spoken primarily by enslaved Africans from various tribes in Suriname, who often did not have an African language in common. Sranan Tongo also became the language of communication between the slaves and the slaveowners. Under Dutch rule, the slaves were not permitted to learn or speak Dutch. As other ethnic groups, such as East Indians and Chinese, were brought to Suriname as contract workers, Sranan Tongo became a lingua franca.

Modern use

Although the formal Dutch-based educational system repressed the use of Sranan Tongo, it gradually became more accepted by the establishment. During the 1980s, this language was popularized by dictator Dési Bouterse, who often delivered national speeches in Sranan Tongo.

Sranan Tongo remains widely used in Suriname and in Dutch urban areas populated by immigrants from Suriname. They especially use it in casual conversation, often freely mixing it with Dutch. Written code-switching between Sranan Tongo and Dutch is also common in computer-mediated communication.[6] People often greet each other in Sranan Tongo by saying, for example, fa waka (how are you), instead of the more formal Dutch hoe gaat het (how are you).

Literature

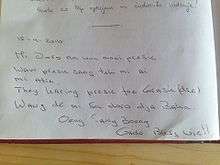

As a written language, Sranan Tongo has existed since the late 18th century. The first publication in Sranan Tongo was in 1783 by Hendrik Schouten who wrote a part Dutch, part Sranan Tongo poem, called Een huishoudelijke twist (A Domestic Tiff).[7] The first important book was published in 1864 by Johannes King, and relates to his travels to Drietabbetje for the Moravian Church.[8]

Early writers often used their own spelling system.[9] An official orthography was adopted by the government of Suriname on July 15, 1986 in Resolution 4501. A few writers have used Sranan in their work, most notably the poet Henri Frans de Ziel ("Trefossa"), who also wrote God zij met ons Suriname, Suriname's national anthem, whose second verse is sung in Sranan Tongo.[10]

Other notable writers in Sranan Tongo are Eugène Drenthe, André Pakosie, Celestine Raalte, Michaël Slory, and Bea Vianen.

See also

- Sranan Tongo phonology and orthography

- Dutch-based creole languages

- English-based creole languages

References

- Sranan Tongo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Sranan Tongo at Ethnologue (14th ed., 2000).

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Sranan Tongo". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sranan

- Sherriah, A (2019). A tale of two dialect regions: Sranan's 17th-century English input (pdf). Berlin: Language Science Press. doi:10.5281/zenodo.2625403. ISBN 978-3-96110-155-9.

- Radke, Henning (2017-09-01). "Die lexikalische Interaktion zwischen Niederländisch und Sranantongo in surinamischer Onlinekommunikation". Taal en Tongval. 69 (1): 113–136. doi:10.5117/TET2017.1.RADK.

- "The History of Sranan". Linguistic Department of Brigham Young University. Retrieved 25 May 2020..

- "Johannes King (1830-1898)". Werkgroup Caraïbische Letteren (in Dutch). Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Suriname: Spiegel der vaderlandse kooplieden". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 1980. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Trefossa en het volkslied van Suriname". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 19 May 2020.

Sources

- Iwan Desiré Menke: Een grammatica van het Surinaams (Sranantongo), Munstergeleen : Menke, 1986, 1992 (Dutch book on grammar of Sranan Tongo)

- Jan Voorhoeve and Ursy M. Lichtveld: Creole Drum. An Anthology of Creole Literature in Suriname. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975.

- C.F.A. Bruijning and J. Voorhoeve (editors): Encyclopedie van Suriname. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Elsevier, 1977, pp. 573–574.

- Eithne B. Carlin and Jacques Arends (editors): Atlas of the Languages of Suriname. Leiden: KITLV Press, 2002.

- Michaël Ietswaart and Vinije Haabo: Sranantongo. Surinaams voor reizigers en thuisblijvers. Amsterdam: Mets & Schilt (several editions since 1999)

- J.C.M. Blanker and J. Dubbeldam: "Prisma Woordenboek Sranantongo". Utrecht: Uitgeverij Het Spectrum B.V., 2005, ISBN 90-274-1478-5, www.prismawoordenboeken.nl - A Sranantongo to Dutch and Dutch to Sranantongo dictionary.

- Henri J.M. Stephen: Sranan odo : adyersitori - spreekwoorden en gezegden uit Suriname. Amsterdam, Stephen, 2003, ISBN 90-800960-7-5 (collection of proverbs and expressions)

- Michiel van Kempen and Gerard Sonnemans: Een geschiedenis van de Surinaamse literatuur. Breda : De Geus, 2003, ISBN 90-445-0277-8 (Dutch history of Surinam literature)

External links

| Sranan Tongo edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Look up Sranan Tongo in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sranan phrasebook. |

| For a list of words relating to Sranan Tongo, see the Sranan Tongo lemmas category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Dictionaries

- SIL International “Sranan wortubuku, Sranan-Nederlands interaktief woordenboek” (Sranan-Dutch interactive dictionary)

- Sranan Tongo Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh list appendix)

- Webster's Sranan-English Online Dictionary

- SIL International “Sranan Tongo – English Dictionary” (PDF format)

- Grammar

- Resources and more

- Begin to learn

- The New Testament in Sranan for iTunes