Sphenophryne thomsoni

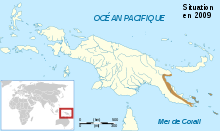

Sphenophryne thomsoni, sometimes known as Thomson's toothless frog, is a species of frog in the family Microhylidae.[2] It is endemic to Papua New Guinea and occurs in the southeastern peninsular New Guinea, Louisiade Archipelago, d'Entrecasteaux Islands, and Woodlark Island.[1][2] It was formerly in its own monotypic genus Genyophryne.[3] The specific name thomsoni honours Basil Thomson, a British intelligence officer, police officer, prison governor, colonial administrator, and writer.[4]

| Sphenophryne thomsoni | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Microhylidae |

| Genus: | Sphenophryne |

| Species: | S. thomsoni |

| Binomial name | |

| Sphenophryne thomsoni (Boulenger, 1890) | |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Description

Sphenophryne thomsoni can grow to 38 mm (1.5 in) in snout–vent length. It is an extremely broad-bodied frog, with the rather flattened head that is as wide or nearly as wide as the body. The fingers are stubby and have no discs. The first toe is extremely short; the other toes are longer and bear small, grooved discs. The snout is rounded. No true teeth are present. The eyes are small. The tympanum is barely visible. Weak supratympanic folds are present. Another pair of more or less distinct skin folds starts near the eyes, converge in the scapular region, and then diverge and fade out. Preserved specimens are dorsally gray to light tan. A dark mark above the posterior edge of the tympanum is usually present, sometimes continuing anteriorly as an ill-defined postocular streak. The dorsal skin folds are accented by dark pigment; symmetrically placed small dark spots are present elsewhere on the dorsum. The ventral surfaces are pale and immaculate.[5]

Use

Sphenophryne thomsoni is used on Tagula Island for magic: it is believed to provide fertility to land if planted.[1]

Habitat and conservation

Sphenophryne thomsoni occurs on forest floor in primary tropical rainforests at elevations below 500 m (1,600 ft).[1] Some specimens were found calling at night during light rain.[5] Development is direct (i.e, there is no free-living larval stage[6]). It is a very abundant species that is not believed to face significant threats—its use on Tagula Island for magic is not occurring at levels that would pose a threat. This species is present in the Kamiali Wildlife Management Area.[1]

References

- Stephen Richards; Allen Allison & Fred Kraus (2004). "Genyophryne thomsoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004: e.T57819A11688169. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2004.RLTS.T57819A11688169.en.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2019). "Sphenophryne thomsoni (Boulenger, 1890)". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Rivera, Julio A; Kraus, Fred; Allison, Allen & Butler, Marguerite A. (2017). "Molecular phylogenetics and dating of the problematic New Guinea microhylid frogs (Amphibia: Anura) reveals elevated speciation rates and need for taxonomic reclassification". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 112: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.04.008. PMID 28412536.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael & Grayson, Michael (2013). The Eponym Dictionary of Amphibians. Pelagic Publishing. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-907807-42-8.

- Zweifel, Richard G. (1971). "Relationships and distribution of Genyophryne thomsoni, a microhylid frog of New Guinea". American Museum Novitates. 2469: 1–13. hdl:2246/2677.

- Vitt, Laurie J. & Caldwell, Janalee P. (2014). Herpetology: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles (4th ed.). Academic Press. p. 166.