Anti-Socialist Laws

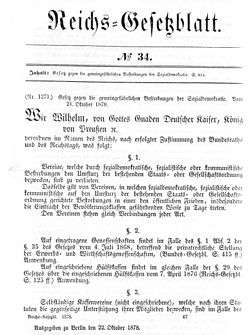

The Anti-Socialist Laws or Socialist Laws (German: Sozialistengesetze; officially Gesetz gegen die gemeingefährlichen Bestrebungen der Sozialdemokratie, approximately "Law against the public danger of Social Democratic endeavours") were a series of acts, the first of which was passed on October 19, 1878, by the German Reichstag (parliament) lasting until March 31, 1881, and extended four times (May 1880, May 1884, April 1886 and February 1888).[1] The legislation gained widespread support after two failed attempts to assassinate Kaiser Wilhelm I by the radicals Max Hödel and Dr. Karl Nobiling. The laws were designed by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck with the goal of reversing the growing strength of the Social Democratic Party (SPD, named SAP at the time), which was blamed for inspiring the assassins. The perks occasion tended to strengthen the socialist, so Bismarck dropped the laws and changed his coalition, becoming an ally of his former enemies the Catholic Centre party, which appealed to Catholic workers to oppose socialism.[2]

Laws

Although the law did not ban the SPD directly, it aimed to cripple the organization through various means. The banning of any group or meeting of whose aims were to spread social democratic principles, the outlawing of trade unions and the closing of 45 newspapers are examples of suppression. The party circumvented these measures by having its candidates run as ostensible independents, by relocating publications outside of Germany and by spreading Social Democratic views as verbatim publications of Reichstag speeches, which were privileged speech with regard to censorship.

The law also banned the display of emblems of the Social Democratic Party. To circumvent the law, social democrats wore red bits of ribbons in their buttonholes. These actions, however, led to arrest and jail sentences. Subsequently, red rosebuds were substituted by social democrats. These actions also led to arrest and jail sentences. The judge ruled that in general everyone has a right to wear any flower as suits their taste, but when socialists as a group wear red rosebuds, it becomes a party emblem. In a final display of protest against this clause of the anti-socialist laws, female socialists began wearing red flannel petticoats, and when they wanted to show a sign of solidarity, they would lift their outer-skirts. Female socialists, especially, would display in protest their red petticoats to the police, who were constrained by social norms of decency from enforcing this new sign of socialist solidarity.[3]

The laws' main proponent was Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who feared the outbreak of a socialist revolution similar to the one that created the Paris Commune in 1871. Despite the government's attempts to weaken the SPD, the party continued to grow in popularity. A bill introduced by Bismarck in 1888 which would have allowed for the denaturalization of Social Democrats was rejected. After Bismarck's resignation in 1890, the Reichstag did not renew the legislation, allowing it to lapse.

Timeline

May 11, 1878: 2 shots fired at Wilhelm I by Max Hödel.

May 17: Prussian government demands the Bundesrat ban the SPD. In the Reichstag only conservatives support the bill.

June 2: Wilhelm I is shot by Dr Karl Nobiling.

June 11: Reichstag dissolved.

July 30: New elections, socialists lose 3 of their 12 seats. Anti-Socialist bill passed by the two conservative parties and the national liberals.

October 19: Bill passed by 221 to 149. Social Democrats voluntarily dissolved the party.[4][5]

November 28: Minor state of siege declared in Berlin, 67 social democrats expelled.

August 21-3 1880: Wyden [6] party congress sees the expulsion of Johann Most and Wilhelm Hasselmann for anarchism by the SPD's moderate wing.

October 28: Minor state of siege in Hamburg.

April 4, 1881: Social Democrats back accident insurance but demand several amendments.[7]

June 1881: Minor state of siege in Leipzig. Local SPD organization destroyed.

September 8: Moderate socialist Louis Viereck begs Engels to tone down the radicalism of the party newspaper Sozialdemocrat[8]

August 19–21, 1882: Secret conference in Zürich organized by Bebel. It partly heals the division between moderates and radicals.[9]

1883: Anti-Socialist laws partly relaxed, strengthening SPD.[10] moderates

March: Secret Copenhagen Congress condemns State socialism.

January 13, 1885: Frankfurt police chief Rumpf stabbed to death by the young anarchist Julius Lieske.[11]

April 2, 1886: Reichstag votes 173 to 146 to renew the anti-socialist laws.

April 11: Prussian interior minister Puttkaner issues the strike decree. It gives the police the power to use the anti-socialist laws against strikers and expel their leaders.

May 11: Political meetings in Berlin now need police permission 48 hours before.[12]

May 20: Minor state of siege in Spremberg.

July 31: 9 Socialist leaders convicted at the Saxon state court for joining an illegal organization.

December 16: Minor state of siege in Frankfurt am Main.

February 15, 1887: Minor state of siege in Stettin.

October 2–6: St. Gall party congress. Bebel defeats his opponents.

Fall: Bismarck fails to get socialist leaders expelled from Germany.

May 2, 1889: Coal miners strike in the Rühr unsupported by SPD

July 14–20: 2nd international founded in Paris.

January 25, 1890: Reichstag refuses to renew the anti-socialist laws.

February 20: Social Democrats win 19.75% of the vote.

March 18: Bismarck resigns.

Some Social Democratic members of the Reichstag during the period

Wilhelm Liebknecht

Wilhelm Liebknecht

(1826–1900) August Bebel

August Bebel

(1840–1913) Wilhelm Hasenclever

Wilhelm Hasenclever

(1837–1889) Johann Most

Johann Most

(1846–1906)

References

- Lidtke (1966), 339.

- John Belchem and Richard Price, eds. A Dictionary of 19th-Century World History (1994) pp 33-34

- "Metropolitan. v.38 1913". HathiTrust. p. 63. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- Lidtke (1966), 119.

- Lidtke (1966), 70–77.

- Lidtke (1966), 82.

- Lidtke (1966), 159.

- Lidtke (1966), 131.

- Lidtke (1966), 135–38.

- Lidtke (1966), 273.

- Lidtke (1966), 125.

- Lidtke (1966), 244–46.

Further reading

- Bonnell, Andrew G. "Socialism and Republicanism in imperial Germany." Australian Journal of Politics & History 42.2 (1996): 192–202.

- Hall, Alex. "The War of Words: Anti-socialist Offensives and Counter-propaganda in Wilhelmine Germany 1890-1914." Journal of Contemporary History 11.2 (1976): 11–42. online

- Lidtke, Vernon L. The Outlawed Party: Social Democracy in Germany, 1878-1890. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966. online free to borrow

- Lidtke, Vernon L. "German social democracy and German state socialism, 1876–1884." International Review of Social History 9.2 (1964): 202–225. online