Sonny Brogan

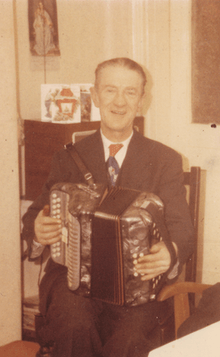

Patrick Joseph "Sonny" Brogan (4 July 1906 – 1 January 1965) was an Irish accordion player from the 1930s to the 1960s, and was one of Ireland's most popular traditional musicians.[2][3][4] He was one of the earliest advocates of the two-row B/C button accordion in traditional music,[5][6] and popularised it the 1950s and 60s. He originally played on a single-keyed Hohner melodeon, and later the two-row Paolo Soprani (pictured) which he used until he died.[5][7] Sonny's Paolo Soprani was one of the rarest, the grey model, made in 1948, when the company still made them by hand. Offaly-born button box player Paddy O'Brien currently has Sonny's accordion.[8]

Sonny Brogan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Patrick Joseph Brogan[1] |

| Born | 4 July 1906 |

| Origin | Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 1 January 1965 (aged 58) |

| Genres | Irish traditional |

| Instruments | Hohner Single-row Melodeon, "Paolo Soprani" Double-row B/C Button Accordion |

| Years active | 1930s–1964 |

| Labels | HMV, EMI, RTÉ, Topic Records |

| Associated acts | Lough Gill Quartet, Ceoltóirí Chualann |

Background

Sonny Brogan was born in Dublin, the eldest of three children born to Alicia Brown and Andrew Brogan.[1] On a holiday trip to Kildare as a young boy, he first heard Irish music played on the accordion by his great uncle, Thomas Cleary. His mother, when opening luggage on returning home, found a melodeon hidden there 'stolen' by Sonny who had taken a fancy to it. He was allowed to keep the instrument and taught himself to play it.

Growing up he attended music classes for piano, and learned how to read basic music notation. He soon found, however that his ear served him better as a teacher, and abandoned "paper music" as he called it. The teacher in question offered to teach Sonny free of charge if he returned, but he declined.

Sonny had a great love of music in general and possessed many 78rpm records of artists like Amelita Galli-Curci, apart from a huge collection of Michael Coleman, the Sligo fiddle player, who he admired more than any other musician.

1930s and 1940s

In the 1930s and 1940s, alongside his close friend Bill Harte, he played with the Lough Gill Quartet.[7][9][10] Sonny gathered a lot of tunes from Bill Harte, some of which he would write down in tonic solfa for the record, and others which he simply committed to memory. It has been said that both Bill Harte and Sonny Brogan "are reputed to have been among the pioneers who saw the potential for Irish music making in the button accordion pitched B/C and subsequently devised and disseminated the fingering method".[11] One of the tunes Sonny recorded with the Lough Gill Quartet, "Toss the Feathers" (78rpm HMV IM948), was his own composition, and he took great pride in playing it on selected occasions.[12]

Sonny went to England briefly in the 1940s, and on his return, George Rowley (fiddler originally from Co. Leitrim) and Ned Stapleton (flute player from Dublin) wrote "Sonny's Return" in honour of him. Ned called it "The Wanderer's Return", but it is more commonly known as "Sonny's Return".[13]

A regular in The Piper's Club in Thomas Street,[14] Dublin, Sonny played alongside John Kelly Sr,[15] Tom Mulligan, Tommy Potts, piper Tommy Reck (who often played at Sonny's home), Leo Rowsome, Sean Seery and many other traditional musicians of the day. Sonny had his own Céilí Dance Band during the 1940s who played in Barry's Hotel and in the Teachers' Club, Parnell Square, Dublin.

"Sonny Brogan's Mazurka"[16] is a very well known Irish Mazurka[10] and has been made popular in more recent years by The Chieftains.

1950s

Sonny was admired by Barney McKenna of The Dubliners (to whom he gave lessons), and got the tune "The Swallow Tail Reel" from Sonny.[17] When the young Co Clare accordion player, Tony MacMahon came to Dublin first in 1957, he made it a priority to seek out Sonny Brogan about whom he heard, meet him and ask for lessons.[18] Tony and Barney regularly visited him for lessons and Tony MacMahon has always to this day given special mention to Sonny at each of his own concerts. He had other pupils and he always urged them to develop their own individual style and not to copy other players. Tony MacMahon and Sonny Brogan have both been cited as influences more recently by Mick Mulcahy.[19]

Sonny Brogan spent much time with Irish accordion player James Keane during Keane's youth in the 1950s and 1960s,[20] and regularly played together with Keane in 'The Fiddlers' club aka 'St Mary's' with many other well-known musicians, including John Egan, "Hυgе″ Tom Mulligan, Finbar Furey and Ted Furey (his father),[21] Des O'Connor, John Joe Gannon and John Joe (father and son box players frοm Horseleap, Co Westmeath), Patrick Keane (James Keane's father), Seán Keane (James Keane's brother), and Mick O'Connor.[22]

Sonny also frequented John Kelly's shop at the end of Capel Street, Dublin, usually to discuss the intricacies of tunes, as customers came and went.[23]

1960s

Sonny was one of the original musicians selected by Seán Ó Riada in 1960 to perform music for the play The Song of the Anvil by Bryan MacMahon, and subsequently became one of the original members of Ceoltóirí Chualann.[24]

In 1963, Sonny wrote an article for the folk music journal Ceol,[6] in which he outlined his reaction to older melodeon style players and those of the current modern style. He showed his unease at the new modern style championed by players such as Joe Burke and Paddy O'Brien, while distancing himself from the intolerance of puristic commentators like Seán Ó Riada, who accused the modern style accordion of being an unworthy instrument for the rich melodic traditions of Ireland, and saw its characteristic melodic techniques as fundamentally alien to his conception of Irish dance music.

Even though he had some reservations about the style, Sonny pointed out the attractiveness of the "bright musical tone", which was drawing a new generation of highly skilled players to the instrument. He was also critical of "this triplet which [younger players of the 1960s] throw in everywhere they can, especially in hornpipes...it has become very monotonous to listen to."[4] Sonny also strongly disagreed with his friend Brendan Breathnach who saw the modern players as having no respect for tradition. In 1963, Brendan Breathnach was commissioned by the Educational Company of Ireland to produce an illustrated book on Irish Dance Music. Sonny provided much of the music, from his knowledge of tunes during the course of several visits to his house, and the Ceol article indicates that Sonny's was the largest individual contribution to this book, and described Sonny as "a man who knows everybody's music", and said that "a keen ear and a very retentive memory...enabled him to store up over the years hundreds and hundreds of tunes.".[4] No 82 of the Reels, "Éilís Ní Bhrógáin", was dedicated to his daughter Éilís.

Seán Ó Riada wrote "One of the very few players who can make their music sound like Irish Music is Sonny Brogan of Dublin. He understands the limitations of his instrument but strives to counteract these, not by wrongly placed ornamentation but by emphasising the traditional elements. His ornamentation is usually confined to a single cut, or grace note, and the roll, as in these reels, where restrained ornamentation and subtle variation are far more telling and eloquent than the fashionable plethora of chromatics. We should always be able to hear the tune distinctly".[25]

On 19 February 1963, Sonny made recordings at RTÉ Studios in Dublin, where he played "Gorman's Reel", "The Hut in the Bog", "Morrisson's Jig", "The Fourpenny Loaf", "Jenny Picking Cockles" and "Repeal of the Union". "Gorman's Reel" and "The Hut in the Bog" were released by RTÉ Funduireacht an Riadaigh, on the triple album Our Musical Heritage (FR003) in 1980.[26]

In May 1964 Senator Edward Kennedy made a visit to Ireland. The Irish Independent of May 30 reports that he made "...an unexpected call on one of Dublin's 'singing pubs' last night and stayed for half an hour listening to Irish ballads including several about the Kennedy ancestral county of Wexford". He was returning from a reception when the cavalcade drew up outside the licensed premises of Mr. Paddy O'Donoghue, Merrion Row, and lively ballads were played by various musicians including Sonny Brogan on accordion, playing with Ronnie Drew, Barney McKenna and Ciaran Bourke.[2]

Tributes

The burial records of Staplestown Cemetery state that Sonny died on the 1st January 1965 and that he was buried the following day.[2] Among those attending the funeral in the snow, and who travelled a long distance in bad weather conditions, was Ronnie Drew.

Tributes were paid to Sonny after his death, and Seán Ó Riada, during the radio programme "Reachtaireacht an Riadaigh" on Radio Éireann, when paying respects to Sonny, said that he "was a library of Irish Music and when you want to find something out you go to the 'library'".

James Keane, Sonny's young friend from the Dublin scene, founded and named a branch of Comhaltas in Sonny Brogan's honour while he was a teenager, shortly after Brogan's death.[27]

John Kelly, the fiddle player, has said that Sonny was the best musician he had ever heard of for his vast knowledge of tunes and the fact that he could remember all the different versions and names of each tune and the history behind them.

Desún MacLiam wrote of him "Is cinnte nach mbéidh a leithéid arí againn" (It is certain we will never have the likes of him again)

Éamon de Buitléar did a special programme on Radio Éireann devoted to Sonny Brogan, on 19 March 1965. Ciarán Mac Mathúna also had often included some of Sonny's recordings in his radio programmes and spoke highly of him.

Seán Ó Riada published the following tribute following Sonny's death :

"It was in the autumn of 1960 that I first met Sonny Brogan. I had been asked to supply music for Bryan MacMahon's play "The Song of the Anvil" at the Abbey Theatre, and has conceived the idea of using a group of traditional musicians for this purpose – the first time, as far as I am aware, that such a step had been taken. It was Éamon de Buitléar who introduced me to Sonny, who was at first rather shy and reserved, until he realised what was wanted of him. The play went on and, though it did not find favour with the public which it more than merited, the music seemed to succeed with everyone, not least of all the actors and backstage staff, who used to be entertained by impromptu concerts given by the musicians in the dressing rooms. Sonny was, of course, a prime mover in all this and one of the reels which they used play most often backstage, commonly called "Redigan's", was re-christened by us privately "The Abbey Reel".

When the run of the play was over I hated the idea of parting from the musicians and so formed "Ceoltóirí Chualann", of which, during the few years we have been functioning Sonny was a mainstay. I would not suggest for a moment that our association was all sweetness and light. Many the argument we had – it is well known that musicians argue more fiercely about traditional music than about anything else. However, we always saw eye to eye in the finish and each argument served only to make us better friends.

Sonny's qualities as a musician were rare. He had an astounding memory, so much so that I was inclined to regard him, with John Kelly, as our living reference library. He could recall three or four different versions of a tune going back through three or four layers of time and often through three or four changes of title. He had a passion for the pure, simple essence of tunes, uncluttered by mistaken ornamentation. He was also, of course, an outstanding accordion player, one of the very few who could make it sound suitable for playing Irish music.

As a person, Sonny was – well, he was contentious, convivial, argumentative, loyal, dogmatic, witty, utterly reliable, a tiger when his temper was roused (which was rare), and at the same time curiously gentle and courteous. He was a good friend. I shall miss him.

Beannacht Dé lena anam."

References

- "National Archives: Census of Ireland 1911". Census.nationalarchives.ie. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- http://www.kildare.ie/ehistory/index.php/sonny-brogan-musician-1906-1965/

- JamesKeane.com

- Ceol:A Journal of Irish Music (Vol1, No2, Published 1963)

- Paolo Soprani and the Irish Box (5) Archived 15 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.jstor.org/pss/852759

- Cooley – sleeve-notes by Tony MacMahon

- "Copperplate Distribution". Copperplatemailorder.com. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- Ceolas: The Fiddler's Companion

- Sonny's Dream Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Sleeve Notes, Irish Dance Music (CD), Topic Records, TSCD602

- "Sample Tune Descriptions · Paddy O'Brien". Chulrua.com. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- "Comhaltas: Paddy Lynn's Delight". Comhaltas.ie. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- News and Comment 13

- John Kelly

- Sonny Brogan's Mazurka – Wikimusica

- Nick Guida. "The Dubliners: Discography – The Dubliners with Luke Kelly". Itsthedubliners.com. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- "Video About". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- Top 10 Albums, 2005 – Earle Hitchner at the Celtic Cafe

- desertlass. "The Irish Cultural Center – Newsletter – Volume 7, Issue 3". Azirish.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- The Vasectomy Doctor: A Memoir – Andrew Rynne – Google Books. Books.google.ie. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- "The Leading Irish Aid Espanol Site on the Net". IrishAidEspanol.org. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- Tony MacMahon's "Player on the Black Keys"

- Irish People and Ireland – Irish news, events in Ireland, Irish culture, genealogy, music, Ireland travel

- Our Musical Heritage, Page 71

- The Irish Traditional Music Archive Database

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)