Soldier Artificer Company

The Soldier Artificer Company was a unit of the British Army raised in Gibraltar in 1772 to work on improving the fortifications there. It was the Army's first unit of military artificers and labourers – the existing Corps of Engineers was entirely made up of commissioned officers – and it replaced the traditional but unreliable practice of employing civilian craftsmen. The company was an immediate success and was responsible for upgrading the British fortress's defences before the Great Siege of Gibraltar.

During the siege between 1779–83, the Soldier Artificer Company played a key role in repairing the damage caused to the fortifications by Spanish bombardments. They also excavated tunnels inside the Rock of Gibraltar to enable the defenders to fire down into the Spanish lines. After the siege, they assisted in rebuilding the civilian settlement at Gibraltar. The Soldier Artificers' numbers were increased several times to a peak of about 250 men organised in two companies. Their success was such that similar units were raised back in Britain to form the Corps of Royal Military Artificers, a predecessor to today's Royal Engineers. The Soldier Artificer Company merged with the Royal Military Artificers in 1797.

History

Establishment

The Soldier Artificer Company was established by Lieutenant Colonel William Green to assist his programme of improvements to the fortifications of Gibraltar. He was posted to the fortress in 1761 as its Senior Engineer and in 1769 he put forward improvement plans which were eventually accepted after much debate.[1] The go-ahead was given in October 1770, when the British Government authorised a major programme of construction works.[2] The works were initially carried out by civilians recruited from England and elsewhere in Europe. They were not subject to military discipline, which made them difficult to manage. The only punishments available for misconduct were reprimands, suspension and dismissal; the latter incurred costs and disruption in having to find replacements. These problems caused significant delays and extra expense in completing the works.[3]

To remedy this situation, Green proposed that a company of military artificers should be raised to work on the fortifications. The garrison had occasionally used the artificing skills of individual soldiers, especially artillerymen, over the previous 70 years. Green's suggestion was welcomed by the Governor and Lieutenant-Governor of Gibraltar and was recommended by them to the Secretary of State for endorsement. It was duly agreed and on 6 March 1772 Royal consent was granted.[4] A warrant was issued authorising the raising of a 68-man company consisting of one sergeant-adjutant, three sergeants, three corporals, one drummer and 60 privates working variously as stonecutters, masons, miners, lime-burners, carpenters, smiths, gardeners and wheel-makers. Officers of the existing Corps of Engineers (which consisted entirely of commissioned officers) were put in command of the newly established Military Company of Artificers. It was almost immediately renamed the Soldier Artificer Company.[5]

Many of the civilian engineers, including almost all of the non-English ones, were dismissed when the Company was established, though a few of the better qualified and more reliable ones were retained. None took up an offer to join the Company.[6] There was little difficulty in finding enough men to make up the numbers, as men from the garrison volunteered to join it.[5] The Company soon proved to be a great improvement on the civilian workforce and a fresh warrant issued on 25 March 1774 authorised its expansion to 93 members, the additions comprising one extra sergeant and corporal and a further 23 private artificers.[7] This proved to be a great improvement on the previous arrangements. General Robert Boyd, the Lieutenant-Governor of Gibraltar, commended the work of the Company in a letter to Lord Rochford, the Secretary of State: "We can depend only upon the artificer company for constant work, and on soldiers occasionally. Had it not been for the artificer company, we should not have made half the progress in the King's Bastion, as well as in the other works of the garrison."[8]

The building of the King's Bastion was one of the most important projects carried out by the Company. It was a key fortification positioned on the waterfront between the fortress's old and new moles. The bastion's foundation stone was laid in 1773 but the progress of its construction was slow at first.[9] It was hindered by the departure of foreign artificers and the loss of manpower resulting from the withdrawal of three Hanoverian regiments which had provided a number of artificers to supplement the Company. It was decided to expand the Company to make up for the shortfall and this was authorised on 16 January 1776, bringing its numbers to 116 non-commissioned officers and men.[8] The Company worked on the bastion "from gun-fire in the morning to gun-fire in the evening, as also on Sundays"[8] and completed it in 1776. The bastion, which mounted over 20 guns and had bomb-proof casemates capable of housing 800 men, demonstrated its military worth only a few years after its completion when it withstood several years of heavy bombardment during the Great Siege of Gibraltar, which began in June 1779.[10]

The Great Siege

The Soldier Artificers played a central role during the siege in successfully defending Gibraltar against the besieging Spanish and French armies. They were divided into three groups to direct works to strengthen the fortifications after the start of hostilities with Spain.[11] At the height of the siege in 1782–83, nearly 2,000 men of the garrison were put to work on the fortifications under the direction of the Soldier Artificers.[12]

On 27 November 1781, after the Spanish had set up their own siege lines, the artificers participated in a highly successful British raid to demolish the Spanish entrenchments and spike their cannon. The Governor, General George Eliott, subsequently praised in a despatch the role they had played in the sortie: they had "made wonderful exertions, and spread their fire with such amazing rapidity, that in half an hour, two mortar batteries of ten 13-inch mortars, and three batteries of six guns each, with all the lines of approach, communication and traverses, &c. were in flames and reduced to ashes. Their mortars and cannon were spiked, and their beds, carriages and platforms destroyed. Their magazines blew up one after another, as the fire approached them."[13] The artificers were also responsible for providing the gunners with a supply of red-hot shot to be fired at the besieging forces, which they accomplished by building kilns around the fortress to heat 100 pieces of shot at a time.[14]

Despite British counter-fire, the Spanish were able to advance slowly along the isthmus linking Gibraltar with Spain by extending their trenches towards the British lines. The closer they came, the more difficult it was for the British to aim their cannon down into the Spanish lines. The near-vertical cliff of the North Front of the Rock of Gibraltar greatly restricted the space in which the British cannon could be deployed.[15] By May 1782 the Spanish had been able to knock out many of the British batteries on the North Front without the British being able to return fire adequately.[16]

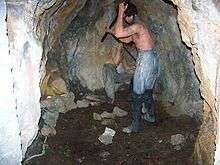

General Eliott offered a bounty of 1,000 Spanish dollars to "any one who can suggest how I am to get a flanking fire upon the enemy's works". In response, the Company's Sergeant-Major, Henry Ince, proposed to tunnel a gallery through the Rock to reach an outcrop called the Notch, so that a cannon could be mounted there to cover the entire North Front.[17] His suggestion was immediately approved and the Soldier Artificers began tunnelling on 25 May 1782. As the works progressed, the tunnellers decided to create an opening in the cliff face to provide them with ventilation. It was immediately realised that this would offer an excellent firing position. By the end of the siege, the newly created Upper Gallery – known today as the Great Siege Tunnels – housed four guns, mounted on specially developed "depressing carriages" to allow them to fire downwards into the Spanish positions. The Notch was not reached until after the siege had ended; instead of mounting a gun above it, the outcrop was hollowed out to create a broad firing position.[15]

Apart from the tunnelling work, the Company was kept busy during the siege by repairing damage caused by the Spanish bombardment of the fortress. Its single worst loss of life during the siege occurred on 11 June 1782 when a Spanish shell hit the magazine of Princess Anne's Battery, causing a devastating explosion. The magazine was completely destroyed and debris was ejected down the slope into the British lines below, causing heavy casualties in the vicinity. Fourteen soldiers were killed and another 15 were wounded. By July the Company had lost 22 men through various causes, six of them killed by enemy action, with the rest falling victim to illnesses.[18] Replacements and an increase in numbers were urgently requested from England. Under a fresh Royal Warrant issued on 31 August 1782, the company's numbers were increased to one sergeant-major, 10 sergeants, 10 corporals, 209 privates and four drummers. The new recruits, numbering 141 men, were quickly despatched to Gibraltar and arrived there in October.[19]

The Company also included two boys, Thomas Richmond and John Brand, dubbed "Shell and Shot" by their older comrades. They were sons of Company sergeants and were trained as, respectively, a carpenter and a mason. They were put to work in the fortifications to look out for enemy shells being fired and give warning of their approach. Their keen eyesight enabled them to save many lives, earning them a fair amount of celebrity within the garrison.[20] The pair were given a proper education after the siege and in due course were commissioned as second lieutenants. Both were posted to the West Indies but died there of yellow fever in 1793.[21]

Rebuilding and merger

By the end of the siege in February 1783, seven men of the Company had been killed and a further 23 had died from sickness, with an additional two men executed in May 1781 for looting. However, it had suffered no desertions during the siege, unlike several of the other British formations in the garrison.[22] The great success of the Company's tunnelling work led to a large-scale programme of further tunnelling leading to 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of tunnels being excavated by 1790. Ince remained in charge of the work.[15] The Soldier Artificers were also occupied with the rebuilding of the civilian settlement at Gibraltar, which had been reduced to ruins, and repairing and further strengthening the fortifications.[23] Their numbers were replenished with men transferred from regiments stationed at Gibraltar.[24] They were uniquely privileged among the garrison's lower ranks; they were exempted from guard duty and their cleaning and cooking was done for them by soldiers of the line.[25]

The structure of the Soldier Artificer Company underwent major reform in June 1786 when it was divided into two companies, in recognition of its increased size. It also underwent a major turnover in personnel, with 86 members being discharged – over a third of its numbers. Apart from disciplinary problems with some Soldier Artificers, the main reason for the mass discharge was that many of them were simply too old and weak to be able to bear the rigours of their work. As experienced craftsmen were required, this meant that their average age skewed much higher than regular units. Due to military necessity, recruits had generally been admitted between the ages of 35–45 and occasionally as old as 50.[26] The older members were replaced with younger men aged 35 or under, primarily masons and bricklayers, and the overall number of Soldier Artificers was increased again.[27] However, the journey of the second batch of new recruits – 58 men, 28 wives and 12 children – ended in disaster on 24 September 1786 when their ship, the Mercury, was shipwrecked on a sand bank off Dunkirk. Only three men were pulled from the water, two of whom died soon afterwards.[28]

The following year, the Master-General of the Ordnance, the Duke of Richmond, proposed to Prime Minister William Pitt that six companies of 100 soldier artificers should be raised in Britain along the lines of the Soldier Artificer Company. [29] Richmond was intent on a major programme of building and renovating fortifications,[30] just as Green had been in Gibraltar 15 years earlier, and like Green he was dissatisfied with the existing system of hiring civilian labourers and artificers. Although the proposal was strongly opposed by those who argued that it was ridiculous to put labourers under military discipline,[31] it was approved by Pitt and King George III and a warrant was issued in October 1787 authorising the creation of the Royal Military Artificers and Labourers. The Soldier Artificers in Gibraltar were asked if they wanted to change their existing scarlet uniforms for the new blue uniforms of their British-based counterparts. They agreed and from 1788 all the soldier artificers in the British Army wore the same uniforms.[32]

In June 1797 the Soldier Artificers were amalgamated with the Corps of Royal Military Artificers, a predecessor to today's Royal Engineers. By this time they comprised two companies with two sergeant-majors, five sergeants, five corporals, two drummers and 125 private artificers in each company (though the actual numbers on amalgamation were somewhat lower than this). Their discipline had deteriorated during peacetime and drunkenness was frequent, as were courts-martial for misconduct. Even so, the quality of their work remained high as long as they were kept under the close scrutiny of their officers and NCOs, who were particularly good foremen. Their incorporation into the corps brought its numbers up to a nominal total of 1,075 men of all ranks.[33]

A statue on Gibraltar's Main Street commemorates the Soldier Artificer Company. It bears the inscription: "Presented to the people of Gibraltar by the Corps of Royal Engineers to commemorate the continuous service given by the corps on the Rock of Gibraltar from 1704, and the formation here in 1772 of the first Body of Soldiers of the Corps, then known as the Company of Soldier Artificers. (26 March 1994)."[34] In 1972, the Gibraltar Philatelic Bureau issued a stamp commemorating the Soldier Artificers and the bicentenary of the Royal Engineers in Gibraltar.[35]

References

- Hills, George (1974). Rock of Contention: A History of Gibraltar. London: Robert Hale & Company. p. 308. ISBN 0-7091-4352-4.

- Connolly, Thomas William John (1855). The History of the Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners, Volume 1. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans. p. 5.

- Connolly, p. 1

- Connolly, p. 2

- Connolly, p. 3

- Connolly, p. 4

- Connolly, p. 6

- Connolly, p. 8

- Connolly, p. 7

- Hills, p. 309

- Connolly, p. 10

- Connolly, p. 20

- Connolly, pp. 12–13

- Connolly, p. 22–3

- Fa, Darren; Finlayson, Clive (2006). The Fortifications of Gibraltar. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 1-84603016-1.

- Connolly, p. 13

- Connolly, p. 14

- Connolly, p. 15

- Connolly, p. 16

- Connolly, p. 32

- Connolly, p. 33

- Connolly, p. 26

- Connolly, p. 39

- Connolly, p. 40

- Connolly, p. 41

- Connolly, p. 44

- Connolly, p. 45–6

- Connolly, p. 46–7

- Connolly, p. 58

- Connolly, p. 55

- Danby, Paul; Field, Cyril (1915). The British Army Book. Blackie and Son. p. 53.

- Strachan, Huw (1975). British Military Uniforms 1768–1796: The Dress of the British Army from Official Sources. Arms and Armour Press. p. 300.

- Connolly, p. 100

- "Royal Engineers' statue, Main Street, Gibraltar". Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Gibraltar 1972 Royal Engineers Bicentenary". Stamps of the World. Retrieved 3 November 2012.