Sofronie of Cioara

Sofronie of Cioara (Romanian: Sofronie de la Cioara) is a Romanian Orthodox saint. He was an Eastern Orthodox monk who advocated for the freedom of worship of the Romanian population in Transylvania.

Sofronie of Cioara "Cuviosul Mărturisitor Sofronie de la Cioara" | |

|---|---|

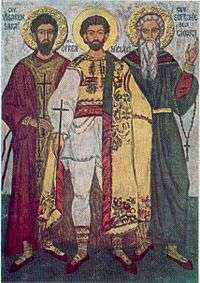

Romanian Saints Visarion Sarai, Nicolae Oprea Miclăuș, Sofronie of Cioara | |

| Eastern Orthodox Monk | |

| Born | Cioara, now Săliştea |

| Died | Curtea de Argeş |

| Venerated in | Romanian Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | 21 October 1955, Alba Iulia by the Romanian Orthodox Church |

| Feast | 21 October |

Early life

Sofronie was born in the first half of the 18th century in the Romanian village of Cioara, now Săliștea, Transylvania, which was at the time part of the Austrian Habsburg Empire. His Christian given name was Stan and his family name was Popa (or Popovici, according to other sources). His family name suggests that one of his ancestors was a priest, as in Romanian popǎ means priest. Sofronie also became an Orthodox priest and he remained in Cioara until the death of his wife, when he went to the a monastery in Wallachia (possibly the Cozia Monastery) and became a monk.

After becoming a monk, Sofronie returned to Cioara and built a small wooden Orthodox monastery in the forest close to the village. He devoted his life to monasticism until 1757, when he started to lead the peaceful uprising of the Romanian Orthodox population in Transylvania against the Habsburg policy of encouraging all Romanians to join the Greek-Catholic Church.

Religion in Habsburg Transylvania

The Habsburg Empire was a conglomerate of different states and people. In this conglomerate, the Roman Catholic religion served to strengthen the other forces of cohesion, dynastic, absolutism, bureaucratic, or military, and provided a political instrument for domination and unification. In addition to various measures designed to protect Catholicism, which at the time was very weak in Transylvania (predominantly Romanian Orthodox), the Habsburgs tried to strengthen it in other ways. The fact that the Romanian people, due to their Orthodox religion, were only tolerated in Transylvania presented an excellent opportunity, and the Habsburgs believed that by winning over the Romanians they would strengthen their position in the region.[1]

In 1701, the Emperor Leopold I decreed Transylvania's Orthodox Church to be one with the Roman Catholic Church. Therefore, Transylvanians were encouraged to become Catholics and adhere to the newly created Greek-Catholic Church by retaining their Orthodox ritual, but accepting the four doctrinal points established by the Council of Florence between 1431 and 1445: the Pope as the supreme head of the church; the existence of Purgatory; the Filioque clause; and the use of unleavened bread in Holy Communion. The clergy first had to be won over with the material advantages of the union, which would mean equality with the Catholic priesthood, including their income and their privileges.[2] However, many of the Orthodox priests did not join the Union and, as Seton-Watson wrote in his book, "despite all handicaps, the devotion of the common people to the ancient faith was truly touching and the latent demand for an Orthodox bishop and freedom of religion slowly became more vocal and was roused by the Uniate example".[3]

Sofronie's movement (1759–1761)

Sofronie, as a Transylvanian Orthodox monk, preached against the union with the Catholics and against the increasing pressure put on the Orthodox communities to join this union. In the spring of 1757, the Austrian authorities from the nearby village of Vinţu de Jos destroyed Sofronie's small monastery in an attempt to eliminate the Orthodox resistance in Transylvania. The authorities also started to arrest all the members of the Orthodox clergy preaching against the union. In order to escape the arrest, Sofronie was forced to leave Cioara, but the Orthodox community of the region, continued to remain faithful to their religion.

After some evidence of popular discontent of the Transylvanian Orthodox, in 1759 the Empress Maria Theresa issued her first Edict of Toleration, which seemed far too modest in scale to the people concerned, and only served to increase disturbances.[4]

On 6 October 1759, Sofronie addressed the Romanian Orthodox community from Brad, in Hunedoara county, informing the people that the Empress' Edict of Toleration allowed the Romanian population in Transylvania to choose freely between the Orthodox and the Greek-Catholic Church. The authorities in Vienna became worried and imperial troops hunted down the preacher. He was arrested by the authorities and jailed in Bobâlna, a village in the Hunedoara county. On 13 February 1760, Sofronie was forcibly released, after the revolt of some 600 Romanian peasants led by the Orthodox priest from Cioara, Ioan.

Sofronie continued his preachings against the Union with Rome in Ţara Zarandului and Ţara Moţilor. On 21 April 1760 he addressed the Romanian Orthodox community from Zlatna, and on 12 May, he addressed the one from Abrud. The Austrian Council of Ministers in Vienna, alarmed by his popularity, decided on 3 June to arrest and then kill Sofronie.

On 2 August in the Abrud Church, Sofronie was once again arrested by the authorities and transferred to Zlatna. After the revolt of some 7,000 peasants from the area, he was once again forcibly released and then guarded and kept in hiding by the peasantry employed in the royal mines of Abrud. For a time, they were in virtual revolt and openly declared that "the power of the lords is at an end, it is we who are now the masters".[3]

On 14–18 February 1761, at Alba Iulia, Sofronie organized a meeting of the Transylvanian Orthodox Synod, which demanded total freedom of worship in Transylvania.[4] The Austrian authorities sent the General Adolf von Buccow to pacify the region and arrest Sofronie, who, just before being arrested, managed to escape to Wallachia, where he had many sympathizers. Sofronie remained in Wallachia until his death. He continued to dedicate his life to Orthodox monasticism, as a monk at the monasteries of Robaia (1764–1766), Vieroşi (1766–1771) and then Curtea de Argeş, all in the Argeș County.

In reprisal for Sofronie's escape to Wallachia, General Buccow had almost all Orthodox monasteries in Transylvania burnt down.[4] However, disturbances went on and, to bring back order, the Empress issued a new Edict of Toleration in 1769, which gave legal status to the "Eastern Greek Cult" (i.e. the Orthodox), making it an official religion in Transylvania. In reality tensions remained, and only under Emperor Joseph II was a climate of religious tolerance brought in with the Edict of 13 October 1781. This resulted in many Romanians going back to the Orthodox Church, showing that an element of compulsion was present in many of the previous conversions.[4]

Results of the movement and its legacy

Sofronie's movement led to the peaceful uprising of the Romanian Orthodox peasant population in order to change the status of their Church from only "tolerated", despite being the majority of the Transylvanian population, to "officially recognised". In the end, the Orthodox achieved a notable victory: recognition by the court of Vienna of the legal existence of their church and the appointment of a bishop in the person of Dionisie Novacovic.[5] He was the first bishop for the Transylvanian Orthodox population since 1701, when the authorities abolished the Orthodox Metropolitanate from Alba Iulia.

Historian Keith Hitchins proposed an explanation for the strong devotion of the common people to their ancient faith, even though the Union with Rome would have brought them many more advantages and privileges.

The movement roused by Sofronie offers valuable insights into popular notions of community. The climate of opinion prevailing in the village, as revealed by the Orthodox resistance to the Union with Rome, strikes one as ahistorical, non-national, and to some extent millenarian. Those who followed Sofronie saw their own lives in terms of the biblical drama of man's fall and redemption. The Christian past was thus their present, continually made real by religious ceremonies. In a sense, they lived in a continuous present, in which ancient beliefs and practices were the models for everyday life. Religion determined their earthly frame of reference, for whenever they thought about membership in a larger community beyond the family or the village, they considered themselves part of the Orthodox world. An ethnic consciousness clearly existed -they were aware of the differences between themselves and the Serbs, for example, and they clung to their 'Wallachian religion'- but the idea of nation as the natural context within which they should live was foreign to them.[5]

The intellectuals linked with the Romanian Greek-Catholic Church had a different approach to the problem of the Romanian nation in Transylvania. They possessed a keen sense of history and they thought increasingly in terms of 'nation', creating in this way a new path of development for the Romanians in Transylvania.

The Orthodox movement led by Sofronie, focused on religion, and the movement of the Greek-Catholic scholars, focused on the idea of nation, in the end had complementary effects. They both kept alive the connection between the Romanians in Transylvania and those from Wallachia and Moldavia and can therefore both be seen as important steps made by Romanians towards their national unity.

References

- Ștefan Pascu, A History of Transylvania, Wayne State University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-8143-1722-7

- Keith Hitchins, The Idea of Nation: the Romanians of Transylvania, 1691-1849, Bucharest: Editura științifică și enciclopedică, 1985.

- Robert William Seton-Watson, A History of the Roumanians, London: Cambridge University Press, 1934, pp. 181-182.

- Georges Castellan, A History of the Romanians, Boulder: East European Monographs, 1989, p. 109. ISBN 0-88033-154-2

- Keith Hitchins, The Romanians 1774-1866, Oxford University Press, 1996, pp. 202-203. ISBN 0-19-820591-0