Snowden Family Band

The Snowden Family Band was a 19th-century African American musical group. The children of the Snowden family of Clinton, Knox County, Ohio, comprised the ensemble. The band's career stretched from before the American Civil War into living memory; no other African American band of their type lasted as long.[1]

Snowden Family Band | |

|---|---|

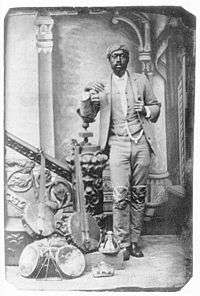

.jpg) Lew and Ben Snowden on banjo and fiddle at their home in Clinton, Knox County, Ohio, c. 1890s | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as |

|

| Origin | Clinton, Knox County, Ohio |

| Genres | |

| Years active | c.1850 - c.1900 |

| Members |

|

The Snowdens earned their living by farming. However, through their music, they integrated themselves into their predominantly white community and entertained, corresponded with, and even taught their white neighbors. A long Knox County tradition credits them with composing (or helping to compose) the song "Dixie".

Performances

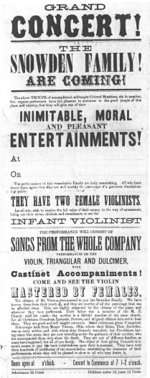

The Snowden children began touring sometime around 1850. Friends and contacts in other towns often invited them to perform, and their advertising consisted of nothing more than a few handbills and word of mouth. This invitation from Arthur Kirby is typical:

As we are going to have a Suinging[2] party the 12th off August on Saturday The neighborhood requested me to drop you a few Line to inform you that They want you to come and give us a Concert on that Same evening. The Suinging part is in The grove is rite by the School House now i want you to be sure and come if you possibly can and if you can come Send me three or four bill if you have got them and i will put Them up for you I am Shure off a Big crowd if you will Come if you can come Send me the Bills by next Saturday if you can if you have no bills Struck wright any how if you will come on that Evening and i will put The word out my Self and the rest of the boys.[3]

Their concert tours lasted for several days and brought them to settlements across rural Ohio. They traveled in a vehicle that one contemporary described as a "sort of stage coach carriage",[4] and they typically stopped in a village or town for a one-night engagement.

Sometimes, offers came to play in more lucrative markets farther afield. Friends wrote from Missouri that "Ben if you and Lue would come Out here you could make A fortune holding concerts."[5] Nevertheless, the band rarely strayed from within a 75-mile (121 km) radius of Clinton.[6]

The band consisted of five regular members from among the seven Snowden children: Sophia, Ben, Phebe, Martha, Lew (or Lou), Elsie, and Annie. Their instruments were common for the mid-19th century, and most were store-bought. Sophia and Annie played fiddle, possibly the only females at the time known today to have done so.[7] The band's handbills advertised this curiosity; one from the 1860s reads, "THEY HAVE TWO FEMALE VIOLINISTS . . . . COME AND SEE THE VIOLIN MASTERED BY FEMALES."[8] The youngest child, Annie, was billed as "the infant violinist".[8] Their fiddle-playing style was likely that used by slaves in the South. That is, they stressed rhythm and improvisation at the expense of melody and prewritten music.[9] Their banjos likely played at a lower pitch than that used by white performers.[10] Ben played fiddle and bones, and Lew played banjo; the Snowdens' banjos were fretless, and one was a six-stringer. Phebe danced. In addition, at least one of the Snowden children played guitar and another the flute. The dulcimer, tambourine, and triangle featured in their act on occasion, and the children also sang.

A Snowden concert began the instant the family came within earshot of a settlement. The children struck up a tune to gather attention as they headed to the concert site, usually a public location such as a schoolhouse, town hall, field, or graveyard. The price of admission was nominal, typically 25¢ for adults and 15¢ for children, and payment could be as informal as dropping something into a passed hat. An average engagement earned the band $11 to $12.[11]

Audiences were primarily white, and the band performed in a manner that was pleasing to such tastes, yet which sustained their connection to their black culture and heritage.[12] Their shows had no great spectacle aside from some animated dancing. They gathered their repertoire from sheet music, mail order, library songsters, and by playing with other musicians. The Snowdens could not read music, so they learned everything by ear. Most of these songs were popular tunes drawn from minstrel shows and circus acts, though the band avoided material that was overly demeaning of black culture or that was written in over-the-top, racist black dialect.[12] Nevertheless, they avoided overtly abolitionist material. Some of their repertoire was from black composers; they sang both "Oh, Dem Golden Slippers" and "In the Morning by the Bright Light" by James A. Bland, for example. They were fairly up to date; the band sang "My Old Kentucky Home" within two years of its composition.[13] Spirituals and hymns comprised another important aspect of their act. Improvisation was common.

Despite their local celebrity, the Snowdens faced the same suspicion as other traveling performers and the racism directed toward blacks in general. White townspeople likely denied them food or lodging at times, and the Snowdens had to be ready to deal with any lawmen who might mistake them for runaway slaves. They relied on their reputation to protect them, and their handbills tried to project this to any who had not heard of them:

The citizens of Mt. Vernon, recommend to you the Snowden Family. We have known them from their youth up, and they are worthy of all the patronage that can be afforded them. They are highly respected by the citizens of this place and wherever they have performed. Their father was a member of the M. E. Church until his death -- the mother is a faithful member of the same church. . . . Good references given if required.[8]

They also touted their wholesomeness. One handbill asked "Christians, Preachers, Lawyers, Doctors" to come see them play.[14] Still, the dangers of travel were known even to the Snowdens' white acquaintances. E. D. Root wrote to Sophia Snowden:

We are all glad to hear from you and we are glad to hear you are all well and have got back home safe and well i hope you have done well by travelling on your account and situation i was wondering what had become of you all a few days a go and we did not know but you ware all dead.[15]

Where they were well known, they often stayed with some distinguished resident for the night.[10] The next morning, they moved on to the next settlement, usually about ten miles (16 km) away. Their itinerary always remained flexible, and tours had no set duration. One friend wrote: "i suppose you have got home buy this time . . . . we have all putt off writing to you so as to bee shure that you may bee at home we thought you may bee gone longer than you expected."[16]

Songs by the Snowdens

Original compositions made up some portion of the Snowden band's repertoire, although they rarely wrote these down. As a result, "We Are Goin to Leave Knox County", written in the 1860s, is the only surviving song of undeniable Snowden origin. Its first verse and refrain bid the Snowden home farewell:

- We are goin to leave knox County

- To lands We Nevre Sean

- With nothing But our violins

- To make the music ring

- fare Well knox conty

- fare Well fore a Whyle

- fare well knox conty Dear

- an friends that on ous Smile[17]

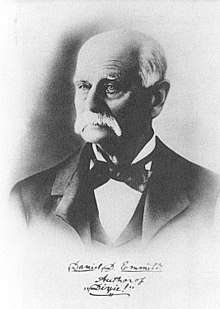

Still, a Mount Vernon, Ohio, tradition credits the Snowdens with at least one other well-known work: "Dixie". The story, now in its third generation, dates to the 1910s or 1920s. It even prompted the local black American Legion post to place a new grave marker on Ben and Lew Snowden's final resting site in 1976, reading, "They taught 'Dixie' to Dan Emmett."[18]

Howard L. Sacks and Judith Rose Sacks propose that the writers of "Dixie" were not Ben and Lew Snowden but their parents, Thomas and Ellen Snowden. The idea also appears in a 1978 genealogy of the Greer family of Ohio, which states that "After the Greers had settled in Knox Co., Ellen [Cooper] stayed with them until she married Tom Snowden, an entertainer whose musical gifts inspired Daniel Emmett to write 'Dixie.'"[19]

The Snowdens made little distinction between music they wrote and music they played, so the idea that they might have collaborated or even given a song to Dan Emmett is therefore not surprising.[20] Evidence does place Emmett where he might have encountered, or even played with, the Snowdens: His grandparents' farm neighbored the Snowdens', his father may have shoed the Snowdens' horses, and his birthplace later became the Snowdens' church. An unpublished biography, written in 1935 by a friend of Emmett's family, places him in Mt. Vernon several times beginning in 1835 and into the 1860s.[21] Furthermore, Ben and Lew Snowden had at least some connection to Emmett. On his death in 1923, one of Lew Snowden's boxes contained a newspaper clipping that named Emmett as composer of "Dixie" and a framed picture of Emmett with "Author of 'Dixie!'" written across it.[22]

Nevertheless, this evidence is, in the end, merely circumstantial. Many scholars, such as E. Lawrence Abel, reject the whole notion of a Snowden connection to "Dixie".[23]

Family life

Thomas Snowden, a freed slave, and Ellen Cooper, a house servant, met and married in Knox County. They had nine children, of whom seven survived infancy. Although Thomas and Ellen Snowden were both illiterate, the children attended white schools and learned to read and write.

The Snowdens were primarily farmers by trade, with their homestead located at Clinton, Ohio, a small village north of Mount Vernon. In July 1856, the 39-year-old Ellen Snowden became the head of household upon the death of Thomas Snowden, 53. The family soon had trouble paying the mortgage on their farm, prompting them by 1859 to add a line to their handbills proclaiming that they were trying "to secure means to pay back indebtedness upon their homestead."[24] In 1864, the bank foreclosed on two of their farm's 8 acres (32,000 m2). Ellen Snowden paid the rest of the mortgage the following year.

Their music allowed the Snowdens to integrate into their mostly white community.[25] Music and the Snowdens were synonymous in the area; the 1860 census for Morris Township in Knox County lists their "Profession, Occupation, or Trade" as "Snowden Band",[26] and an 1876 city directory for Mount Vernon lists them as "Snowden Minstrels".[27] The Snowdens played local events, or received invitations telling them, for example, that "Snowden & Mrs. Snowden Are Respectfully Invited to attend a Birthday Party At Mr. Samuel Alberts of their daughter on Monday Evening. Please bring your music."[28] George Root, a white man, even asked to live with the family during the Civil War so that he could take singing and fiddling lessons.[7]

When not performing for profit, the Snowdens played for fun and practice in their Clinton home. In later years, Ben and Lew Snowden, on fiddle and banjo respectively, played in the second-story gable of their house for whomever would listen. Their home faced Samuel Smith's tavern, and Smith's patrons often took drinks over to the Snowden yard to enjoy the music.

Despite their reputation, the Snowdens were not immune to prejudice. In 1864, Ellen Snowden sued white neighbors who were preventing her from planting crops; she won the case. Days after the passing of the 15th Amendment on 3 February 1870, a local official prevented Ben Snowden from voting. Snowden sued the man but ultimately lost the case. Beginning in 1878, Ben Snowden, aged 38, courted a 23-year-old white woman named Nan Simpson, who lived in Newville, Ohio, just north of Knox County. Their affair lasted two years before Ellen Snowden learned of it and put a stop to the relationship.[29]

Socially the Snowdens professed conservative values, praising in their letters and music such concepts as women's virtue, temperance, and piety. They attended the African Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the few in the United States at the time that used instruments during the worship service.[30] Less conservatively, they supported abolitionism, though never overtly.[1]

By 1900, Ben and Lew Snowden were the last remaining members of the family. They took up racehorse driving as a hobby and continued to farm, but it was still their music that defined them. They performed from their home's gable, and the next generation of fiddlers most likely sought them out. Though there is no hard evidence to prove such meetings occurred, both John Balzell and Dan Emmett likely knew the Snowdens and played with them on occasion.[31] Ben Snowden died in 1920, and Lew Snowden in 1923. They left no known heirs.

Notes

- Sacks and Sacks 12.

- Swinging, a type of dance.

- Kirby, Arthur (July 1876). Letter to Ben Snowden. Knox County. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 66. Spelling and punctuation as in original.

- Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 64.

- Scott, Alta, and Scott, Alven (9 June 1883). Letter to Ben and Lew Snowden. Missouri. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 66. Spelling and punctuation as in original.

- Sacks and Sacks 11.

- Sacks and Sacks 91.

- Snowden handbill, reprinted in Sacks and Sacks 58.

- Sacks and Sacks 62.

- Sacks and Sacks 64.

- Sacks and Sacks 66.

- Sacks and Sacks 14.

- Sacks and Sacks 75.

- Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 103.

- Root, E. D. (no date). Letter to Sophia Snowden. Pataskala, Ohio. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 148. Spelling and punctuation as in original.

- Root, George (no date, c. Civil War). Letter to the Snowdens. Harrison, Ohio. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 64. Spelling and punctuation as in original.

- Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 57. Spelling and punctuation as in original.

- Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 3.

- McMillan, Jean Irwin (1978). The Greer Family Genealogy: Descendants of Robert and Ann Emerson Greer. Columbus: J. I. McMillan, p. 1. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks.

- Sacks and Sacks 161.

- Sacks and Sacks 168.

- Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 183.

- Abel 49.

- Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 80.

- Sacks and Sacks 88-9.

- 1860 census for Knox County, Morris Township, 16. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 59.

- White, John W., compiler (1876). White's Mount Vernon Directory, and City Guide, vol. 1, 1876-77, 121. Gambier, Ohio: Argus Book and Job Office. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 59.

- Albert, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel (20 January 1879). Letter to Ben, Lew, and Ellen Snowden. Mount Vernon, Ohio. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 88.

- Sacks and Sacks 148-9.

- Sacks and Sacks 73.

- Sacks and Sacks 193-4.

References

- Abel, E. Lawrence (2000). Singing the New Nation: How Music Shaped the Confederacy, 1861-1865. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books.

- Sacks, Howard L. and Sacks, Judith Rose (1993). Way up North in Dixie: A Black Family's Claim to the Confederate Anthem. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.