Smile surgery

Smile surgery or smile reconstruction is a surgical procedure that restores the smile for people with facial nerve paralysis. Facial nerve paralysis is a relatively common condition with a yearly incidence of 0.25% leading to function loss of the mimic muscles.[1] The facial nerve gives off several branches in the face. If one or more facial nerve branches are paralysed, the corresponding mimetic muscles lose their ability to contract.[2] This may lead to several symptoms such as incomplete eye closure with or without exposure keratitis, oral incompetence, poor articulation, dental caries, drooling, and a low self-esteem.[3][4] This is because the different branches innervate the frontalis muscle, orbicularis oculi and oris muscles, lip elevators and depressors, and the platysma. The elevators of the upper lip and corner of the mouth are innervated by the zygomatic and buccal branches.[5] When these branches are paralysed, there is an inability to create a symmetric smile.[3]

| Smile surgery | |

|---|---|

Before and after dynamic smile reconstruction in facial paralysis | |

| Specialty | Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery |

Smile surgery is performed as a static or dynamic reconstruction. An example of static reconstruction is upper and lower lip shortening or thickening with commissure preservation.[6] Dynamic smile reconstruction procedures restore the facial nerve activity.

Historical background

The first known surgical repair of an injured facial nerve was performed by Drobnick in 1879, who connected the proximal spinal accessory nerve (innervates trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles) to the paralysed facial nerve. More symmetrical features were the result. In 1971 a new technique for facial nerve reconstruction was introduced, as Scaramella and Smith reported on the technique of cross facial nerve grafting (CFNG) for reconstruction of a coordinated smile in unilateral facial paralysis cases. Harii et al. for the first time used a free muscle transfer in combination with a nerve transfer in 1976. Eight years later, Terzis introduced the "babysitter" procedure, which consists of a combination of CFNGs and a simultaneous partial hypoglossal to facial nerve transfer. In 1989, Zuker et al. suggested the use of the masseteric nerve as possible donor nerve for innervation of the transplanted muscle in patients with Moebius syndrome.[2]

Indications

The main indications for dynamic smile reconstruction are unilateral or bilateral facial paralysis due to acquired and congenital causes.[2] Trauma, Bell's palsy and tumour extirpation are examples of secondary or acquired facial paralysis. Bell's palsy or idiopathic facial paralysis is a condition which leads to facial paralysis, however, without a known cause. It has an acute onset and is mostly self-limiting. But if spontaneous recurrence of (near) normal function does not take place, surgical reanimation may be indicated. Some head and neck tumours invade or compress the facial nerve leading to facial paresis or paralysis. Examples of such tumours are facial neuromas, cholesteatomas, hemangiomas, acoustic neuromas, parotid gland neoplasms or metastases. Sometimes, the facial nerve cannot be preserved during resection of these tumours.

Congenital facial paralysis occurs usually unilaterally and may be complete or incomplete. The most common congenital cause is the Moebius syndrome. Moebius syndrome is a congenital neurological disorder with bilateral paralysis of both the facial and abducens nerves. Therefore, lateral eye movement and facial animation are absent. In Moebius-like syndrome, only one side of the face is affected, but with additional nerve palsies of the affected facial and abducens nerve.[3]

Surgical techniques

Selection of the type of nerve transfer is based on the individualised needs and condition of the patient. Individual factors can be patient age, type of paralysis (partial or complete, uni- or bilateral), denervation time of the mimetic muscles, availability of nerve grafts and medical condition of the patient.[2]

If facial paralysis is caused by trauma or tumour surgery, direct reinnervation of the facial muscles (ideally within 72 hours after facial nerve damage) can be achieved by neurorrhaphy, with or without an interposition nerve graft. (Algorithm 1)[7] Neurorrhaphy is a primary end-to-end reconnection of the facial nerve stumps.[8] However, tension-free reconnection is needed, otherwise scar formation can occur and axons will regenerate outside the facial nerve.[9] If a tension-free reconnection is not possible, interposition nerve grafts are an option.[8][9] Mostly the great auricular nerve or sural nerve is used as a graft between the two facial nerve stumps.[8]

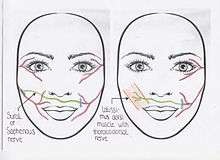

In more long standing acquired facial paralysis either a CFNG procedure or "babysitter" procedure are the indicated techniques, with or without a free muscle transfer.(Algorithm 1)[2] Secondary facial paralysis with a denervation time of less than 6 months can be treated with one or more cross facial nerve grafts (CFNGs).[2] During a cross facial nerve graft procedure one or more branches of the non-paralysed facial nerve are divided and connected to one or more sural nerve grafts which are tunnelled to the affected side of the face. Whether these nerve grafts are immediately attached to the paralysed facial nerve branches or after 9 to 12 months depends on the chosen procedure.

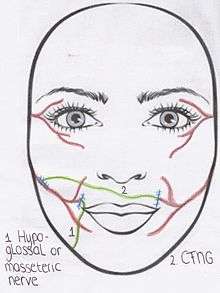

If facial paralysis lasts between 6 months and 2 years, the "babysitter" procedure may be used.(Algorithm 1)[2] During this operation both CFNGs and part of an undamaged donor nerve on the affected side are used.[10] For example, the hypoglossal nerve[10] or masseteric nerve on the affected side can be used as donor nerves. This donor nerve is then attached to the distal end of the paralysed facial nerve.[5] A free muscle transplant is sometimes indicated after the "babysitter" procedure has been performed, depending on the continuity of the injured facial nerve. In other words, if there is contraction of the mimetic muscle during an electromyogram.[10] After a denervation time of approximately more than 2 years, atrophy of the mimetic muscles is permanent.[5] In these cases a free muscle transfer is always performed in combination with a CFNG.[2]

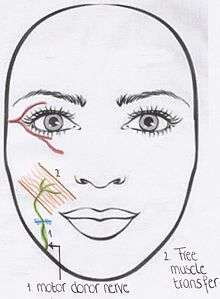

The procedure of choice for congenital facial paralysis is either CFNG or motor donors, both with a free muscle transfer. (Algorithm 2) Incomplete bilateral Moebius syndrome has the same clinical features as the Moebius syndrome, however some motor function is still apparent on one side of the face.[3] This incomplete syndrome is reanimated with the use of the CFNG and free muscle transfer. The cross facial nerve graft comes from the side with some motor function of the facial nerve. However it first has to be investigated if the motor function of the nerve is strong enough to be separated.[2] A free muscle transfer is always used on the paralysed side, as the muscle is a congenital atrophic muscle. Complete bilateral Moebius syndrome is treated with motor donor nerves on both sides.[2][3] Optional motor donor nerves are: the masseteric nerve, accessory nerve or hypoglossal nerve. In rare cases when these nerves are also affected, cervical nerve branches can be used.[2] The use of a free muscle transfer is again indicated.[3] The nerve that initially innervated the free muscle transfer is then connected to the provided branches of the motor donor nerve. In Moebius-like syndrome the CFNG is performed, as the facial nerve on the affected side does not have a strong enough motor function. A free muscle transfer is also used, due to the atrophic muscle.[2][3]

Surgical procedures

Based on the preference of the surgeon, the gracilis muscle, latissimus dorsi muscle, or pectoralis minor muscle are used as free neurovascular grafts. The gracilis muscle is mostly used free neurovascular muscle, because it has a reliable anatomy and is relatively simple to harvest.[11] In addition, it can be trimmed for the correct size and volume[11] with preservation of superior contraction qualities compared to bipennate muscles, because the gracilis is a parallel-fibered or strap muscle.[12] Another advantage is the possibility for simultaneous dissection by a second team while the first team is preparing the face for the free muscle transplant. Another option for a free muscle transfer is the latissimus dorsi muscle. A disadvantage is that it can only be harvested with the patient in lateral decubitus or prone position. Therefore, the patient has to be turned during the operation. Advantages of the latissimus dorsi muscle are its reliable anatomy and relatively simple dissection. Analogue to the gracilis muscle, this muscle can be trimmed to the correct size and volume. The latissimus dorsi muscle is also a parallel-fibered muscle.[12] Its long neurovascular bundle makes a one-stage facial reanimation without a CFNG possible. By using the long thoracodorsal nerve of the latissimus dorsi muscle, direct coaptation to the facial nerve on the other side can be performed.[12]

The third option is the pectoralis minor muscle, which is mainly used in children. Advantages of this muscle are its relatively small size and flat and fan-like shape, obviating the need for trimming without bulkiness as a result.[7] In addition, the pectoralis minor muscle has a muscle fibre orientation that is much alike with the facial muscles.[12] However, as dissection of this muscle is rather difficult and the neurovascular anatomy is variable, nowadays surgeons tend to use it less frequently. Furthermore, the pectoralis minor muscle is not a parallel-fibered muscle, and it is oversized in adults.[7]

During a one-stage or two-stage CFNG procedure, one or more non-affected facial nerve branches are used for reinnervation of the paralysed side. In the one stage procedure a free muscle transplant with a latissimus dorsi graft or a nerve graft (using the sural nerve or saphenous nerve) can be used. The latissimus dorsi graft is used because of its long thoracodorsal nerve. Therefore, it can be coapted directly to the normal functioning facial nerve.[12] The one stage CFNG, implies an end-to-side coaptation of the sural or saphenous nerve to the distal end of the affected facial nerve.[6] In the two-stage procedure, an incision in front of the ear is made on the non-paralysed side. Upon electrical stimulation, the nerve which produces the best contraction of the zygomatic muscles (and so the appearance of a smile) is selected.[5] This branch is then sectioned. The sural or saphenous nerve as cross facial nerve graft is coapted to this unaffected branch of the facial nerve and tunnelled across the face to the paralysed side through a subcutaneous tunnel.[10] The end of the graft is positioned in front of the tragus (cartilage in front of the ear) on the paralysed side. Nine to twelve months is needed for axonal regeneration in the cross facial nerve graft, because the result of damaged nerve tissue is loss of structure and axonal function. Degeneration appears distally in the paralysed facial nerve but this takes time, this process is called Wallerian degeneration. During the second stage end-to-side or end-to-end nerve coaptation to the proximal end of the paralysed facial nerve is performed with a microscope.[5] And a free muscle transplant is placed, if indicated.

Likewise the "babysitter" procedure uses the CFNG, in combination with the masseteric or hypoglossal nerve. In the "babysitter" procedure, the hypoglossal nerve or masseteric nerve on the affected side is identified. This donor nerve is then attached to the distal end of the paralysed facial nerve.[5] Techniques for donor nerve transfers are transposition of the entire donor nerve, partial transposition by splitting the donor nerve longitudinally[2] or indirect hypoglossal- or masseteric-facial anatomosis using a 'jump' interposition graft.[8] This usually is the great auricular nerve or sural nerve. These hypoglossal- or masseteric-facial nerve anastomosis using a 'jump' interposition graft can be used to directly reinnervate the paralysed facial muscles or as a "babysitter" procedure. The goal of the latter is only to achieve fast reinnervation of the mimetic muscle to prevent irreversible atrophy. Simultaneously one or more CFNGs are performed to eventually reinnervate the mimetic muscles, again as a one- or two-stage procedure,[13] depending on the choice for the free muscle transfer graft. If a two-stage procedure is performed, the CFNGs are connected to the distal branches of the paralysed facial nerve during the second stage 9 to 12 months later. The donor nerve can be left intact. If a free muscle transfer is indicated, this is also performed in the second stage of the procedure to augment the partially reinnervated mimic muscles by the hypoglossal nerve.[10]

In case of longstanding facial paralysis with irreversible muscle atrophy and unavailability of a suitable donor facial nerve, a free muscle graft is indicated for smile restoration, which has to be reinnervated by another donor nerve (usually the masseteric nerve) in an end-to-end fashion. Through an incision in front of the ear, the cheek flap is elevated below the underlying layer of fat. Here the nerve stimulator can be used in identifying the donor motor nerve to the masseter muscle. Once the nerve is identified, it is dissected from its connections and traced into the muscle to free as much length as possible.[2]

Results

All procedures in general show an improvement of symmetry of smile and patient satisfaction, although time of recovery differs between different approaches. Primary neurorrhaphy provides the best possible outcome, as the anatomy and function of the damaged facial nerve is restored.[7][8] After primary neurorrhaphy of the facial nerve mean recovery time typically is 6 to 12 months.[9] The contraction amplitude after using a CFNG is usually not very powerful, but it results in a relatively spontaneous smile because the contralateral healthy facial nucleus controls the movements.[14] After a CFNG procedure the first signs of reinnervation usually occur between 4 and 12 months.[15] The use of the masseteric nerve provides an amount of movement that is within the normal range, resulting in a more symmetrical but not completely emotional smile.[14] Nerve transfers using the hypoglossal or masseteric nerves and the "babysitter" procedure result in first contractions of the mimic muscles after approximately 4 to 6 months.[4][5] However, after the use of the hypoglossal nerve control of facial movements is hard to obtain by the patient and a spontaneous smile may not occur at all.[5]

True spontaneity of a smile will not occur at the same rate in all dynamic smile reconstructions. A spontaneous smile is smiling without consciously thinking about it.[14] The primary neurorrhaphy and free muscle transfer are the only options to restore a true spontaneous smile.[7][13] Although the masseteric nerve transfer provides a strong smile within the range of normal, it never becomes truly spontaneous and emotional.[14] But with practice, the majority of patients can provide a spontaneous smile some of the time[14] due to the plasticity of the cerebral cortex.[13] Effective rehabilitation can also prevent biting whilst smiling, when using the masseteric nerve as nerve transfer.[14]

Complications

There are several complications, however, most patients find them less invalidating than the inability to smile.[14] General postoperative complications are infection of the muscle donor site,[15] facial abscess, hypertrophic scars,[3] hematoma,[15] and swelling of the face or muscle donor site.[14] In some cases of incomplete facial paralysis, the procedure had a decline in function as a result. However, this improved after only a few months.[15] Almost all procedures show synkinesis, meaning involuntary movements appear during the voluntary movements. In primary neurorrhapy, with or without an interposition graft, perineural fibrosis is a common complication.[8] With the use of the CFNG there is a risk of sensory deficits in the lower part of the leg, due to the sural or sapheneous nerve graft.[2] A complication seen with the use of the masseteric nerve is the inability to chew without the appearance of a smile.[14] The hypoglossal nerve as a donor nerve can induce tongue atrophy due to denervation.[5]

References

- Werker, P.M.N (2007). "Plastische chirurgie bij patienten met een aangezichtsverlamming". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 151: 287–294.

- Terzis JK, Konofaos P (May 2008). "Nerve transfers in facial palsy". Facial Plast Surg. 24 (2): 177–93. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1075833. PMID 18470829.

- Bianchi B, Copelli C, Ferrari S, Ferri A, Sesenna E (November 2010). "Facial animation in patients with Moebius and Moebius-like syndromes". Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 39 (11): 1066–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2010.06.020. PMID 20655175.

- Lindsay RW, Hadlock TA, Cheney ML (July 2009). "Bilateral simultaneous free gracilis muscle transfer: a realistic option in management of bilateral facial paralysis". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 141 (1): 139–41. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.03.005. PMID 19559974.

- Faria JC, Scopel GP, Ferreira MC (January 2010). "Facial reanimation with masseteric nerve: babysitter or permanent procedure? Preliminary results". Ann Plast Surg. 64 (1): 31–4. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181999ea9. PMID 19801918.

- Static Reconstruction for Facial Nerve Paralysis at eMedicine

- Frijters E, Hofer SO, Mureau MA (August 2008). "Long-term subjective and objective outcome after primary repair of traumatic facial nerve injuries". Ann Plast Surg. 61 (2): 181–7. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181591e27. PMID 18650612.

- Tate JR, Tollefson TT (August 2006). "Advances in facial reanimation". Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 14 (4): 242–8. doi:10.1097/01.moo.0000233594.84175.a0. PMID 16832180.

- Shindo M (October 1999). "Management of facial nerve paralysis". Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 32 (5): 945–64. doi:10.1016/S0030-6665(05)70183-3. PMID 10477797.

- Terzis JK, Tzafetta K (October 2009). ""Babysitter" procedure with concomitant muscle transfer in facial paralysis". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 124 (4): 1142–56. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b2b8bc. PMID 19935298.

- O'Brien BM, Pederson WC, Khazanchi RK, Morrison WA, MacLeod AM, Kumar V (July 1990). "Results of management of facial palsy with microvascular free-muscle transfer". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 86 (1): 12–22, discussion 23–4. doi:10.1097/00006534-199007000-00002. PMID 2359779.

- Harii K, Asato H, Yoshimura K, Sugawara Y, Nakatsuka T, Ueda K (September 1998). "One-stage transfer of the latissimus dorsi muscle for reanimation of a paralyzed face: a new alternative". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 102 (4): 941–51. doi:10.1097/00006534-199809040-00001. PMID 9734407.

- Watanabe Y, Akizuki T, Ozawa T, Yoshimura K, Agawa K, Ota T (December 2009). "Dual innervation method using one-stage reconstruction with free latissimus dorsi muscle transfer for re-animation of established facial paralysis: simultaneous reinnervation of the ipsilateral masseter motor nerve and the contralateral facial nerve to improve the quality of smile and emotional facial expressions". J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 62 (12): 1589–97. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2008.07.025. PMID 19010754.

- Manktelow RT, Tomat LR, Zuker RM, Chang M (September 2006). "Smile reconstruction in adults with free muscle transfer innervated by the masseter motor nerve: effectiveness and cerebral adaptation". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 118 (4): 885–99. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000232195.20293.bd. PMID 16980848.

- Takushima A, Harii K, Okazaki M, Ohura N, Asato H (April 2009). "Availability of latissimus dorsi minigraft in smile reconstruction for incomplete facial paralysis: quantitative assessment based on the optical flow method". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 123 (4): 1198–208. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819e2606. PMID 19337088.