Skinner's Room

"Skinner's Room" is a science fiction short story by American-Canadian author William Gibson, originally composed for Visionary San Francisco, a 1990 museum exhibition exploring the future of San Francisco. It features the first appearance in Gibson's fiction of "the Bridge", which Gibson revisited as the setting of his acclaimed Bridge trilogy of novels. In the story, the Bridge is overrun by squatters, among them Skinner, who occupies a shack atop a bridgetower. An altered version of the story was published in Omni magazine and subsequently anthologized. "Skinner's Room" was nominated for the 1992 Locus Award for Best Short Story.

| "Skinner's Room" | |

|---|---|

| Author | William Gibson |

| Language | English |

| Series | Bridge trilogy |

| Genre(s) | Science fiction |

| Published in | Visionary San Francisco Omni |

| Publication type | Exhibition catalogue, periodical |

| Publisher | Prestal Omni Publication International |

| Media type | Video, print (magazine) |

| Publication date | 1990 November 1991 |

| Followed by | Virtual Light |

Synopsis

The story takes place in a near-future where the United States is in decline, having been negatively affected by some event referred to as the "devaluations." It is set in a decaying San Francisco in which the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge is closed and taken over by the homeless.[1] The wealthy denizens of the city have retreated to gated-access enclaves.[2] The room mentioned in the title is a shack built on top one of the bridge's towers.[3] Skinner has lived on the bridge, and in his room, for a long time, and is accompanied by a girl with an interest in the history of the bridge town and who arrived only three months before.

The story reveals that, long ago, the Bridge had been closed to vehicle traffic (for three years) and that the pressure to find somewhere to live had forced homeless people to seize the bridge and set up a squatters' town there.[4] The community that arose was vibrant and was watched by the world's media. The town grew in a piecemeal fashion, built from salvaged parts as well as from material apparently donated by more wealthy nations. At the end of the story Skinner has a dream in which he remembers being at the front of the crowd who seized the bridge (Skinner is the first onto the bridge) and scaled the towers.[4]

Publication history

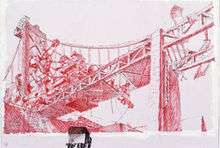

"Skinner's Room" was commissioned by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art for its exhibition "Visionary San Francisco", shown from June 14 to August 26, 1990.[5][6] Gibson's story inspired a contribution to the exhibition by architects Ming Fung and Craig Hodgetts. Ming and Hodgetts designed the urban environment which would have catalysed the transformation of the Bridge.[7] They envisioned a San Francisco in which the rich live in high-tech, self-sufficient, self-contained towers, above the decrepit city and its crumbling bridge, isolated from the amorphous city.[7][8][9] The crate-packaged installation, which was surrounded by scrap metal, computer chips, and pages from manga comic strips, featured a model of the towers, along with Gibson on a monitor discussing the future and reading from "Skinner's Room".[7][10]

A slightly different version of the short story was featured in the November 1991 issue of Omni.[4] The OMNI version concerns an unnamed girl and an old man named Skinner who live in the one-room shack built on top of the first cable tower of the Bridge. This version was collected in Gardner Dozois' 1992 anthology The Year's Best Science Fiction: Ninth Annual Collection,[11] and in Larry McCaffery's After Yesterday's Crash (1995).[12]

Significance

"Skinner's Room" is the first appearance of the Bridge in Gibson's fiction.[13] In the acknowledgments at the end of his 1994 novel Virtual Light, Gibson writes that the short story later developed into the novel;[13] the character of Skinner is one of the main characters in Virtual Light and the setting and characters of "Skinner's Room" are revisited in the sequels to the novel, Idoru and All Tomorrow's Parties (collectively known as the Bridge trilogy).

The New York Times hailed the "Visionary San Francisco" exhibition as "one of the most ambitious, and admirable, efforts to address the realm of architecture and cities that any museum in the country has mounted in the last decade".[9] Despite organiser Paulo Polledri's claim that the collaboration was an "appeal to civic responsibility by showing the effects of its absence",[7] The New York Times judged Ming and Hodgetts's reaction to "Skinner's Room" a "powerful, but sad and not a little cynical, work".[9] After its 1991 republication in OMNI, "Skinner's Room" was nominated for the Locus Award for Best Short Story in 1992.[14]

See also

- Kowloon Walled City, a former squatters' town in Hong Kong and subject of Gibson's fascination.

References

- Burkhart, Dorothy (June 15, 1990). "Seeing a City as it Was—and as it Could be Changing, Challenging San Francisco". San Jose Mercury News. p. 14D.

- Russell, Conrad (2002). "Dream and Nightmare in William Gibson's Architectures of Cyberspace" (.pdf). Altitude. 2 (3). ISSN 1444-1160.

- Tatsumi, Takayuki (2006). Full Metal Apache. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-8223-3774-6.

- Gibson, William (November 1991). "Skinner's Room". Omni. Omni Publication International.

- Zinovich, Jordan (1994). Canadas: Kanaki. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e). ISBN 0-9698433-0-5.

- Polledri, Paolo (1990). Visionary San Francisco. Munich: Prestal. ISBN 3-7913-1060-7. OCLC 22115872.

- Polledri, Paolo (Winter 1991). "Dreamscape, Reality and Afterthought". Places. 7 (2).

- Smith, Hazel (1997). Improvisation, Hypermedia and the Arts since 1945. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers. p. 261. ISBN 3-7186-5878-X.

- Goldberger, Paul (1990-08-12). "In San Francisco, A Good Idea Falls With a Thud". Architecture View. The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- S. Page. "William Gibson Bibliography / Mediagraphy". Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- Gardner Dozois, ed. (1992). The Year's Best Science Fiction: Ninth Annual Collection. St. Martin's. ISBN 0-312-07889-7.

- McCaffery, Larry (1995). After Yesterday's Crash. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-024085-3.

- Rapatzikou, Tatiani (2004). Gothic Motifs in the Fiction of William Gibson. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 181. ISBN 978-90-420-1761-0. OCLC 55807961.

- "The Locus Index to SF Awards: 1992 Locus Awards". Locus. Charles N. Brown. Archived from the original on 2012-07-04. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

External links

- Skinner's Room title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database