Sjønstå

Sjønstå is a settlement in Norway and was officially a village during a brief time when Sulitjelma Mines carried out activity in the area, c. 1890 to 1956. Before this time, Sjønstå comprised the Sjønstå farm, which is located on Øvervatnet (Upper Lake) in the municipality of Fauske in Nordland county.

Sjønstå | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Sjønstå at the mouth of the Sjønstå River. The Sjønstå farm lies right of the river's mouth. | |

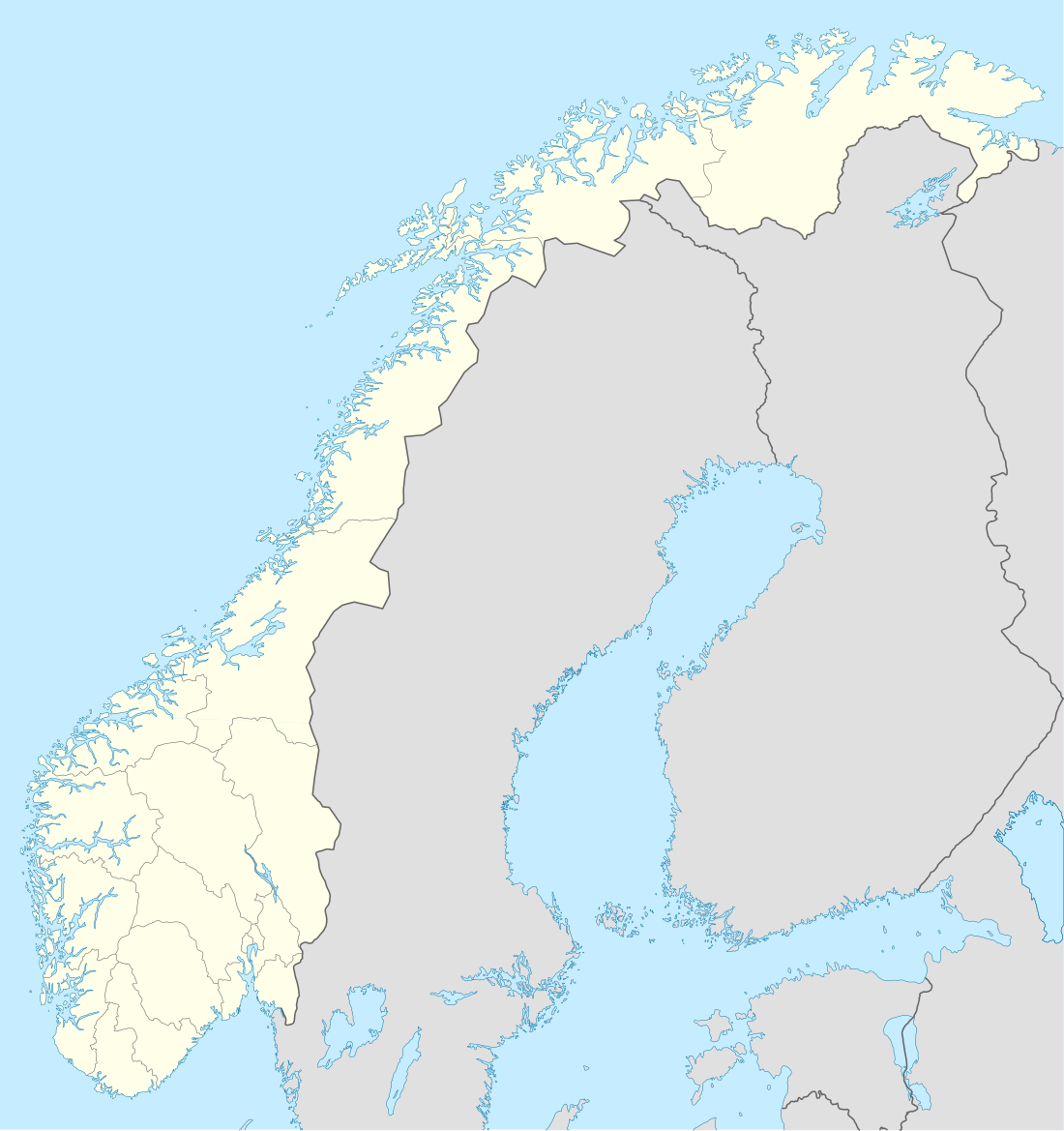

Sjønstå Location in Nordland  Sjønstå Sjønstå (Norway) | |

| Coordinates: 67°12′18″N 15°42′55″E | |

| Country | Norway |

| Region | Northern Norway |

| County | Nordland |

| District | Salten |

| Municipality | Fauske |

| Elevation | 138 m (453 ft) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Post Code | 8200 Fauske |

The Sjønstå River empties into the lake at Sjønstå. Where it enters the lake, there is a sandy beach on the west side of the river's mouth. There are also natural terraces from moraine deposits. The old farm is located on the sandy beach and the terraces were used for tilled fields and meadows.

The Sjønstå farm was given protected status in 2006 by the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage.[2] It represents a special kind of farm known as a cluster farm (Norwegian: klyngetun);[3][4] these were typical in Nordland county before 1900 and few of them have been preserved. The Sjønstå farm is the only remaining cluster farm in Northern Norway and has national significance.[5]

Name

The origin of the place name Sjønstå is uncertain. According to Oluf Rygh, the name may be derived from the word skinstøde; that is, a place where the cows habitually hide or seek shade in the summer heat against bot flies (or horse-flies and deer flies). He states that the name is a compound shortened from skinstøde-å, with the second element aa or å meaning 'river'.[6] Locally, the place is referred to as Sjønståg, Skjønståga, and Sjønstaa. Over time, the name has been written in many different ways in public documents.[7]

History

The Sjønstå farm

The Sjønstå farm appeared in historical sources for the first time in a rent roll from 1665 under the name Süinstad, listing a tenant named Baard Pedersøn.

The farm was not included in the land committee's register of 1661, nor in the tithe list compiled between 1663 and 1665, and so it is likely that the farm was established in 1665.[7]:11

The property register one year later listed two tenant farmers at Sjønstå: the previously named Baard Pedersøn and Guttorm Pedersøn. It is possible that the two were brothers. The register states that the farm had recently been cleared on crown common land and that it would pay the highest rate in tax, which was ½ våg (9.25 kg or 20.4 lb) of stockfish as a public levy. The annual tithe to the church was ¾ tønne (104 l or 3.0 U.S. bu) of grain and 16 marks (3.75 kg or 8.3 lb) of cheese. Furthermore, the land rent (landskylden; i.e., the rent that a tenant or leaseholder had to provide to the owner of the farm, which in this case was the king) was set at one våg (18.5 kg or 41 lb) of stockfish. The high taxes may indicate that Sjønstå was a deserted farm after the Black Death in the Middle Ages. However, no archaeological finds from the Middle Ages have been discovered, and some have suggested that the Sjønstå farm, like other farms around Øvervatnet, was newly cleared in the second half of the 1600s.[7]:11

The residents of the farm settled on the lowest terrace at the outflow of the Sjønstå River, and they had meadows and fields on the other terrace levels. The soil was light and good, a mixture of sand and humus.[7]:11 The property register of 1666 states that the two properties at the site were seeded with one tønne of grain and the livestock consisted of one horse, eight cows, one head of young cattle, seven sheep, and four goats.[7]:14

A description from 1820 stated: "The soil is sandy. The grain harvest is fairly safe. The harbor entrance is deep. ... The forest provides the farm with the necessary fuel and something to sell. The farm is subject to flooding." There have been some increases in production since the farm was first referred to, but they have not been great. Life was often difficult at the location, and the steep hillsides and precipitous mountains formed natural boundaries that prevented expansion.[7]:14

The Sjønstå farm was royal property, and its owners were tenants of the state. In 1800 the farm was divided into two equally sized portions and sold. The first farm was called Nergård ('lower farm'), and the skipper and landowner Christen Ellingsen from the inner Leivset farm in Fauske obtained the deed in 1801. Neither he nor the subsequent owners ever stayed on the farm, but instead leased it to crofters. This farm was sold to Sulitjelma Mines in 1891. The second farm was called Øvergård ('upper farm'), and it was sold to Sulitjelma Mines at the same time as Nergård.[7]:14–15 After the farms had been sold, lease agreements were established with the mining company; farming continued at Nergård until 1956, and the bachelor Andor Karolius Hansen lived at Øvergård until his death in 1973.[7]:22

The waterway was a natural thoroughfare for those that lived at Sjønstå, and fishing was an important source of livelihood in addition to agriculture, just as was common for people along Skjerstad Fjord. The farm made use of the sea with fishing equipment and boats both Sjønstå and Finneid, and a half share in a fisherman's shack in Skrova. The fact that people at Sjønstå also had connections with the larger world is shown by a few of the inhabitants of Sjønstå listed with debt to Bergen merchants at Bryggen in the early 1800s. Sjønstå was thus not a farm cut off from the world, but participated in the rest of society at the time.[8]

Sjønstå as a station on the Sulitjelma Line

In 1892 the Sulitjelma Line was built between Sjønstå and Fossen. The ore from the mining operations was transported by boat across Langvatnet (Long Lake) from Sulitjelma to Fossen, and then by rail from Fossen to Sjønstå to be taken by boat via Øvervatnet (Upper Lake) and Nedrevatnet (Lower Lake), so that it could be sent by ship from Finneid along Skjerstad Fjord. In 1956 the rail line was extended to Finneid and the transshipment activity at the Sjønstå station came to an end.

As a junction, Sjønstå was a location with key personnel for the railroad and boats. Several community associations were soon started, such as a lodge, a shooting club, and a sports clubs (the Sjønstå sports club was founded in 1916).[7]:22[9]

Protection

There are currently about 20 farm buildings at the Sjønstå farm, and the site is divided into an inner farm and an outer farm. The inner farm consists of four houses and four elevated granaries (stabbur). The outer farm consists of a cowshed, storehouse, barn, woodshed, and stall. The buildings have remained unchanged since the 1800s and have a village-like feel.[7]:10

In 2006, the Sjønstå farm was given protected status by the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage. The decision was based on its connection with the history of Sulitjelma Mines and also the fact that it represents a farm layout that was typical in Nordland county before 1900 but has rarely been preserved.[5]

References

- "Sjønstå, Fauske (Nordland)" (in Norwegian). yr.no. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Ingvaldsen, Jan-Olav. 2013. Har brukt seks millioner på å berge gården fra 1600-tallet. Nordlys (October 25).

- Sutherland, Mark Thurber. 1995. Case Studies in Norwegian Community Housing. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, p. 15.

- Østerud, Øyvind. 1978. Agrarian Structure and Peasant Politics in Scandinavia: A Comparative Study of Rural Response to Economic Change. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, p. 89.

- Riksantikvaren: Klyngetun i Fauske fredet.

- Rygh, Oluf. 1905. Norske Gaardnavne, vol. 11. Kristiania: Fabritius.

- Berg, Gunnar. 1990. Sjønstå – en matrikkelgård som forsvant. Fauskeboka 1990. Fauske: Fauske Kulturstyre.

- Tove Mette Mæland . Sjønstå Gård. Digitalt fortalt.

- Enge, Kåre. 1980. Et tidsbilde fra århundereskiftet. Fauske 1905-1980. Fauske: Fauske kommune, p. 52.