Sir John Taylor, 1st Baronet

Sir John Taylor FRS (1745 – 8 May 1786) was a fellow of the Royal Society who was created a baronet of Lysson Hall in Jamaica. He lived in London but he died in Jamaica.

%3B_Zoffany%2C_Johann.jpg)

John Taylor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1745 |

| Died | 8 May 1786 |

| Nationality | British |

Background

Taylor was born in the Colony of Jamaica in 1745 to Patrick and Martha Taylor. His Scottish father had been born with the surname Tailzour in Borrowfield, but he Anglicised his name to Taylor when they married.[1][2]

Relationship with his brother

John's eldest brother, Simon Taylor (sugar planter), used their father's inheritance to purchase a number of sugar plantations, bought slaves, and increased the family wealth. He also became a Jamaican attorney who represented a large number of absentee plantation owners. Simon became reputedly the richest person in Jamaica, and possibly the British empire, becoming a member of the House of Assembly of Jamaica in the process. Simon's wealth derived from slave plantations funded John's extravagant lifestyle in Britain and Europe.[3]

John Taylor became a baronet on 1 September 1778. In the same year he married an heiress, Elizabeth Goddin Haughton only daughter of Philip Haughton and Mary Brissett, owners of slave plantations Orange, Venture and Unity in Hanover Parish, in western Jamaica. They eventually had six children.[4]

While Simon carefully built up his wealthy sugar and slave plantations in Jamaica, he was often critical of his younger brother's extravagant lifestyle.[5]

John Taylor's death

Simon persuaded his brother John to return to Jamaica to take control of his estates in Hanover, which were not failing without his close attention. However, within a year of arriving in Jamaica, John Taylor died in 1786 during a visit to Simon's Lyssons plantation in the eastern end of the island. His title was taken by his son, Simon.[6]

Simon's inheritance

The elder Simon Taylor died in 1813 and left most of his estates to John's son, Sir Simon Richard Brissett Taylor, 2nd baronet. However, Simon the elder also made some provisions for his mixed-race family.[7] John Taylor's son lived only until 1815 which meant the end of the baronetcy.[8] The fortune was inherited by John Taylor's daughter, Anna Susannah, who had married George Watson, who then added her surname to his.[1]

Legacy

John Taylor was captured in a painting by Johann Zoffany of the Tribuna of the Uffizi in Florence in the 1770s. He appears to the right of the painting with Thomas Patch and Sir Horace Mann, 1st Baronet.[9]

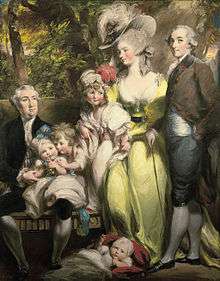

The year before he died, John Taylor and his family were sketched in pastels by Daniel Gardner. The group consisted of Taylor, his wife Elizabeth, his brother Simon Taylor, and four of his children; Simon Richard Brisset, Anna Susanna, Elizabeth and Maria. Simon became the second and last baronet of Lysson Hall.[10]

In addition to the paintings, Taylor is also a key figure in correspondence that is now preserved as a record of life in Jamaica.[1] The letters are from Simon to John and they record world events, the state of the plantations and complaints from Simon that he is doing all the work and John is spending all the money.[11]

References

- Taylor family of Jamaica (1770–1835) Archived 2003-05-01[Date mismatch] at the Wayback Machine, Casbah.ac.uk, retrieved 23 October 2014

- Christer Petley, White Fury: A Jamaican Slaveholder and the Age of Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 19.

- Petley, White Fury pp. 35-6, 81-2.

- Petley, White Fury, pp. 83-6.

- Petley, White Fury, pp. 82-6.

- Petley, White Fury pp. 86-7.

- [http://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9781137465863 "'Washing the Blackamoor White’: Interracial Intimacy and Coloured Women’s Agency in Jamaica", Meleisa Ono-George in Will Jackson and Emily Manktelow (eds), Subverting Empire: Deviance and Disorder in the British Colonial World (Palgrave, 2015), pp.42-60; http://www.ijsl.stir.ac.uk/issue4/livesay.htm Extended Families: Mixed-Race Children and Scottish Experience, 1770–1820], Daniel Livesay, International Journal of Scottish Literature, Spring/Summer 2008

- A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage. p. 211. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- A key to the people shown, oneonta.edu, retrieved 17 October 2014

- "Plantation Life in the Caribbean Part 1". Adam Matthew Publications. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Simon Taylors papers, retrieved 25 October 2014

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Taylor, 1st Baronet. |