Sinkang Manuscripts

The Sinckan Manuscripts (Chinese: 新港文書; pinyin: Xīngǎng wénshū; Wade–Giles: Hsin-kang wen-shu; also spelled Sinkang or Sinkan) refers to a series of leases, mortgages, and other commerce contracts written in Sinckan, Taivoan, and Makatao; they are commonly referred to as the "fanzi contracts" (Chinese: 番仔契; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: hoan-á-khè). Some are written only in a romanized script, while others were bilingual with adjacent Han writing. Currently there are approximately 140 extant documents written in Sinckan; they are important in the study of Siraya and Taivoan culture, and Taiwanese history in general although there are only a few scholars who can understand them.

History and background

The Sinckan language was spoken by the Siraya people that lived in what is now Tainan. During the time when Taiwan was under the administration of the Dutch East India Company (Dutch Formosa 1624–1662), Dutch missionaries learned Sinckan to facilitate both missionary work and government affairs. They also created a romanized script and compiled a dictionary of the language, teaching the natives how to write their own language.

In 1625, Maarten Sonck, the Dutch governor of Taiwan, requested that the Netherlands send two to three missionaries to Taiwan for the purpose of converting the natives. However, the first group to arrive were visiting missionaries who did not have the authority to perform baptism rites. It was not until June 1627 that the first real minister, Rev. Georgius Candidius, arrived, upon which missionary work in Taiwan began in earnest. The first area to be targeted, the Sinckan settlement (modern-day Sinshih), had many converts by 1630.

In 1636, the Dutch started a school for the Sinckan that not only featured religious instruction, but also provided schooling in Western literature. Because the Dutch advocated that missionary work be conducted in the native language, the school was taught in the Sinckan language. The missionary Robertus Junius recorded in his 1643 education report that the Sinckan school had enrolled 80 students, of which 24 were learning to write and 8 to 10 had solid penmanship, while in neighboring Baccaluan (modern-day Anding) school there were 90 students, of which 8 knew how to write.

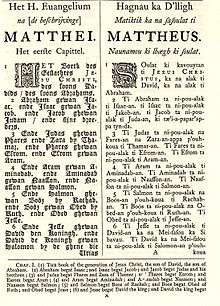

Aside from proselytizing, the missionaries also compiled dictionaries and books of religious doctrine; they translated the Gospel of Matthew into Sinckan and also compiled a vocabulary of Favorlang, another aboriginal language.[2] These would become important sources for later research. The most important Sinckan documents were the contracts between the Sinckan and the Han settlers, commonly known as the Fanzi contracts.

Although the Dutch only governed Taiwan for 38 years, they greatly influenced the development of indigenous culture. To take the Sinckan Manuscripts as an example, the latest extant documents in the Sinckan script date back to 1813 (more than 150 years after the Dutch left Taiwan in 1662). This is evidence to show that "the arts of reading and writing introduced by the Dutch were handed down from generation to generation by the people themselves."[3]

Origins

Shortly after the founding of Taihoku Imperial University in 1928, one of the scholars in the linguistics department, Naoyoshi Ogawa (小川尚義), gathered together a number of old texts in Tainan. In 1931, Naojirō Murakami (村上直次郎) edited and published them under the title The Sinckan Manuscripts.[4] The compilation contained 109 "fanzi contracts," of which 87 were from the Sinckan settlement; 21 of those were bilingual in Han characters and Sinckan.

Notes

- Campbell & Gravius (1888), p. 1.

- Davidson (1903), p. 48.

- Campbell (1903), p. 540.

- Naojirō Murakami (1933). 新港文書 [Sinkan manuscripts]. Taihoku: 臺北帝国大學文政學部. OCLC 26709196.

Bibliography

- Campbell, William (1903). "Explanatory Notes". Formosa under the Dutch: described from contemporary records, with explanatory notes and a bibliography of the island. London: Kegan Paul. LCCN 04007338.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, William; Gravius, Daniel (1888). The Gospel of St. Matthew in Formosan (Sinkang dialect) with corresponding versions in Dutch and English (in Austronesian, Dutch, and English). London: Trubner. OCLC 844610148.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects : tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1887893. OL 6931635M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- 新港文書的收集、整理和解讀,李壬癸,中央研究院 (in Chinese)

- 荷蘭統治之下的臺灣教會語言學---荷蘭語言政策與原住民識字能力的引進(1624~1662),賀安娟,臺北文獻 : 頁81-119,1998 (in Chinese)

- The theme: 荷蘭統治之下的臺灣教會語言學 (in Chinese)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sinckan Manuscripts. |

- 臺灣歷史辭典:新港文書 (in Chinese)

- 中央研究院民族學研究所數位典藏:新港文書 (in Chinese)

- 消失的「新港文書」,李壬癸,中時電子報,2004-08-29 (in Chinese)