Simon of Trent

Simon of Trent (German: Simon Unverdorben, lit. 'Simon Immaculate'; Italian: Simonino di Trento), also known as Simeon (1472–1475), was a boy from the city of Trent, in the Prince-Bishopric of Trent, whose disappearance and death was blamed on the leaders of the city's Jewish community, based on the confessions of Jews obtained under judicial torture.

Simon of Trent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1472 Trento, Prince-Bishopric of Trent, Holy Roman Empire (now Italy) |

| Died | March 1475 Trento, Prince-Bishopric of Trent, Holy Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church (Folk Catholicism) |

| Beatified | Veneration permitted 1588 by Pope Sixtus V |

| Canonized | No |

| Feast | 24 March |

| Attributes | Youth, martyrdom |

| Patronage | Children, kidnap victims, torture victims |

| Controversy | Blood libel |

Catholic cult suppressed | 1965 by Pope Paul VI |

Events

At the time of the events, Prince-Bishop Johannes Hinderbach reigned in Trent under the ultimate jurisdiction of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III. In March 1475, an itinerant Franciscan preacher, Bernardine of Feltre, had delivered a series of sermons in Trent in which he vilified the local Jewish community. That Jewish community consisted of three households headed by Samuel (who arrived in 1461), Tobias, and Engel.[1] They formed a distinct community marked by their professions — Samuel was a moneylender and Tobias a physician — and by their apparent wealth in comparison with the artisans and sharecroppers of the city.[2] The Prince-Bishop had renewed the Jewish community's permission to reside and practice their professions in Trent a few years previously, in 1469.[3] This dependence on the protection of the authorities later inclined the Jews, upon finding Simon's body, to report the discovery.[4]

The events themselves have been reconstructed from a careful study of the trial records by American historian Ronnie Hsia. Simon, aged almost two and a half, went missing about 5 p.m. on the evening of Thursday, 23 March 1475. The following day, Good Friday, Simon's father approached the prince-bishop to ask for help in finding his missing child.[5] The podestà, Giovanni de Salis, had his men spread a description of Simon through the city. Over the following couple of days, searches were carried out by Simon's family and neighbours, by the servants of the podestà, and also by the Jewish community, who had been alerted to a rumour that they had taken the child and were concerned about the possibility of being framed.[5][4] On Saturday, 25 March, Simon's father appealed to the podestà specifically to search the Jews' houses, saying he had been advised they might have taken his child.[5] Despite these searches, no sign of the child was found. Samuel's property was extensive, including a hall that functioned as a synagogue, and a water cellar that was also used for ritual bathing and was supplied with water from a channel that ran beneath the property.[6] According to the trial record, on Easter Sunday, 26 March, a cook named Seligman went to Samuel's cellar to fetch water to prepare the evening meal and found Simon's body in the water. Samuel himself, accompanied by two other Jews, went to the podestà to report the discovery.[4] Later that evening, the podestà and some of his men retrieved the body, with his servant Ulrich being ordered to carry it to the hospital.[7] The narrative summary based on the trial documents, drafted in 1478-1479, omitted the fact that the Jews had themselves reported finding the body, stating only that Ulrich had found Simon's body in a ditch next to Samuel's house.[5]

Following the report of the body's discovery, the entire Jewish community (both men and women) were arrested and forced under torture to confess to having murdered Simon to use his blood for ritual purposes (a classic example of the blood libel that Jews used Christian blood in their rituals). An examination of the corpse by city doctors determined that Simon had not died of natural causes but had been exsanguinated. In Hsia's view, "the narrative imperative, the official story of ritual murder, the trial record of 1475-76, represents nothing less than a Christian ethnography of Jewish rites".[8]

Fifteen of the Jews, including Samuel, the head of the community, were sentenced to death and burnt at the stake. The Jewish women were accused as accomplices but argued their gender did not allow them to participate in the rituals restricted to men. They were freed from prison in 1478 due to papal intervention. One Jew, Israel, was allowed to convert to Christianity for a short while, but he was arrested again after other Jews confessed he was part of the Passover Seder. After a long period of torture he was also sentenced to death on 19 January.[9] The Trent trial's notoriety inspired a rise in Christian violence towards Jews in the surrounding areas of Veneto, Lombardy, and Tirol, along with accusations of ritual murder, culminating in Vicenza with the prohibition of Jewish moneylending in 1479 and the expulsion of all Jews in 1486.[10]

Papal investigation

On 3 August 1475, Pope Sixtus IV commanded Bishop Hinderbach to suspend judicial proceedings until the arrival of the papal representative, Battista dei Giudici, Bishop of Ventimiglia, who would conduct a joint investigation with the Bishop of Trent. Giudici arrived in Trent in September. The local authorities worked against his investigation, preventing him from visiting Jews in prison and impeding his access to trial records.[11]

In the face of persistent hostility, he relocated to Rovereto, which was then under Venetian control,[11] and summoned Hinderbach and the podestà to answer for their conduct. Instead of appearing, Hinderbach had an account of the proceedings drawn up to vindicate his own actions, circulating it widely and so giving general credence to the notion that Simon of Trent had in fact been murdered by Jews.

The case was reviewed in Rome, where Hinderbach had powerful friends, including the papal librarian Bartolomeo Sacchi, who accused Giudici of being in the pay of the Jews. Giudici wrote two treatises on the affair, an Apologia Iudaeorum defending the Jews, and an Invectiva contra Platinam (aimed at Sacchi) defending himself.[11] A committee of cardinals, chaired by Giovan Francesco Pavini, former professor of canon law at the University of Padua and an old friend of the bishop of Trent, exonerated Hinderbach and censured Giudici. A papal bull was issued on 20 June 1478, accepting that the inquiries in Trent had been carried out in legal fashion but avoiding a finding of fact with regard to Simon's death, while also reasserting papal protection for the Jews and the unlawfulness of ritual murder trials, in line with a decree of Pope Innocent IV from 1243.[12]

Veneration

Simon became the focus of attention for the local Catholic Church. The local bishop, Hinderbach of Trent, tried to have Simon canonized, producing a large body of documentation of the event and its aftermath.[13] Over one hundred miracles were directly attributed to Saint Simon within a year of his disappearance, and his cult spread across Italy, Austria and Germany. However, there was also skepticism from the beginning, as Giudici's investigation showed.

Maximilian I, a future Holy Roman Emperor, was a strong proponent of Simon's veneration and commissioned a silver monument of the child.[14] He also had Simon's relics carried in procession when he was made emperor in 1508.

The veneration received wider liturgical impetus in the 16th century. Joannes Molanus included a footnote on Simon of Trent in his 1568 edition of Usuard's martyrology,[15] and this was then incorporated into the new official edition of the Martyrologium Romanum in 1583,[16] with 24 March having the additional text: Tridenti passio sancti Simeonis pueri, a Judaeis saevissime trucidati, qui multis postea miraculis coruscavit. ("At Trent, the suffering of the holy boy Simeon, barbarously murdered by the Jews, who was afterwards glorified by many miracles.")[17] In 1584 the use of this martyrology became obligatory in the Roman Rite. Furthermore, in 1588 Pope Sixtus V gave recognition to the local veneration of Simon as an established devotion, functionally equivalent to a decree of beatification.[14] Simon could thus be considered a martyr and a patron of kidnap and torture victims.

In 1758, Cardinal Ganganelli (later Pope Clement XIV, 1769–1774) prepared a legal memorandum which, to the exclusion of all other allegations of ritual murders of infants which records were thoroughly made available to him, expressly admitted as proven only two: that of Simon of Trent and that of Andreas Oxner.[18] At the same time, he extols the glories and accomplishments of the Jewish people across history, writing that the murder of Simon of Trent does not suffice to injure the reputation of the entire Jewish people.[19]

Simon's cultus was permitted by the Popes for local public liturgical observance (effectively beatification) within the Diocese of Trent.[14] In an Apostolic Letter to Fr. Benedetto Vetrani, Promoter of Faith, dated 22 February 1755, Pope Benedict XIV recognised that this was the case, but was careful to distinguish such authorisation from canonisation:[20][21][22] "It is simply untrue to say that the Church has canonized little Simon of Trent. A decree of beatification was issued by Sixtus V, which took the form simply of a confirmation of cultus and which allowed a Mass to be said locally in honour of the boy martyr. Everyone knows that beatification differs from canonization in this, that in the former case the infallibility of the Holy See is not involved, in the latter it is."[23]

Pope Paul VI removed Simon from the Roman Martyrology in 1965. "Simon of Trent is not in the new Roman Martyrology of 2000, nor on any modern Catholic calendar."[14]

Controversies

In the 21st century, historian Ariel Toaff, writing about the case of Simon of Trent, hypothesized that the notion that some Jews killed children to use their blood for ritual purposes may have been tenuously based on an actual "ritual of blood" that did not involve infanticide. After criticism, the book was withdrawn from circulation and redacted by its author.[24][25]

In 2020, the Italian artist Giovanni Gasparro painted a depiction of Simon's death. He was later accused of Antisemitism for this painting.[26]

Image gallery

- Altobello Melone, Simon of Trent, ca.1521, oil on panel, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Trent (Italy)

- Unknown painter, Ex voto; fresco, end of the 15th century, church of Santa Maria Annunciata, Bienno (BS), Italy

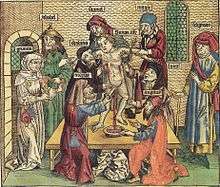

- Incunabulum of Friedrich Creussner, Nuremberg, 1475

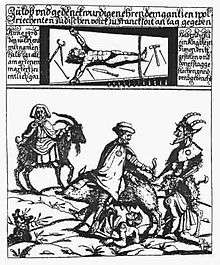

- Simon of Trent's martyred body. Engraving, Nürnberg, around 1479.

Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent

Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent Illustration in Hartmann Schedel's Weltchronik, 1493

Illustration in Hartmann Schedel's Weltchronik, 1493 Unknown painter, fresco, end of the 15th century, church of Santa Maria Annunciata, Bienno (BS), Italy

Unknown painter, fresco, end of the 15th century, church of Santa Maria Annunciata, Bienno (BS), Italy Statue of Simon of Trent on the facade of a palace in Trento (situated in "Via del Simonino")

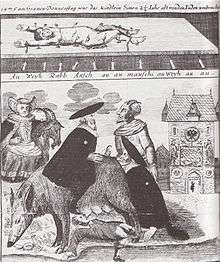

Statue of Simon of Trent on the facade of a palace in Trento (situated in "Via del Simonino") Martyrdom of Simon of Trent above a Judensau.

Martyrdom of Simon of Trent above a Judensau. Martyrdom of Simon of Trent above a Judensau.

Martyrdom of Simon of Trent above a Judensau.

See also

References

- (Hsia 1992, p. 14-15)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 25)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 16)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 26-27)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 1-3)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 16)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 29)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 94)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 95–104)

- (Hsia 1992, p. 128–129)

- Diego Quaglioni (2001). "Giudici, Battista dei". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). 56.

- (Hsia 1992, p. 127)

- Paul Oskar Kristeller, "The Alleged Ritual Murder of Simon of Trent (1475) and Its Literary Repercussions: A Bibliographical Study ", in: Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Vol. 59 (1993), pp. 103-135. JSTOR 3622714

- Kohl, Jeanette (2018). "A Murder, a Mummy, and a Bust: The Newly Discovered Portrait of Simon of Trent at the Getty". Getty Research Journal. Getty Research Institute (10): 37–60. doi:10.1086/697383. ISBN 978-1-60606-571-6 – via Google Books.

- Molanus, Usuardi Martyrologium (Leuven, 1568). On Google Books.

- Caesar Baronius, Martyrologium Romanum ad nouam Kalendarii rationem et ecclesiasticae historiae veritatem restitutum, Gregorii XIII. Pont. Max., iussu editum; accesserunt notationes atque tractatio de martyrologio Romano (Antwerp, Plantin Press, 1589), p. 139.

- Martyrologium Romanum (Venice, 1583), p. 50. On Google Books.

-

- "Un Mémoire de Laurent Ganganelli sur la Calomnie du Meurtre Rituel". Revue des études juives (in French). XVIII. Ed. Peeters. January–March 1889. pp. 179 et seq – via Google Books.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "The Bull Beatus Andreas of Pope Benedict XIV". romancatholicism.org. Archived from the original on 2013-06-20. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- Benedictus XIV (1782). "Beatus Andres de Pago". Sanctissimi domini nostri Benedicti papae XIV. Bullarium. Tomus primus decimus Tomus octavus, in quo continentur constitutiones, epistolae, aliaque edita ab initio pontificatus usque ad annum 1755 (in Latin). National Library of Naples. sumptibus Bartholomaei Occhi. p. 234.

- Pope Benedict XIV, Apostolic Letter to Fr. Benedetto Veterani, Promoter of Faith, 22 February 1755, pp. 144-162, in Bullarium – via Google Books.

- The Month. CXXIII. Longmans, Green, and Co. January–June 1914. p. 78 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Lisa Palmieri-Billig (7 February 2007). "Historian gives credence to blood libel". The Jerusalem Post.

- Adi Schwartz (24 February 2008). "Bar-Ilan Scholar Recants Controversial Blood Libel Theory". Haaretz.

- Reich, Aron. "Italian artist accused of antisemitism for new painting of blood libel". Jerusalem Post. March 27, 2020.

Sources

- Hsia, R. Po-chia (1992). Trent 1475: Stories of a Ritual Murder Trial. Yale University. ISBN 0-300-06872-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Simon of Trent. |