Simexco and Simex

Simexco and Simex were the names of two companies that were created in 1940 and 1941, respectively in Brussels and Paris on the orders of Red Army Intelligence officer Leopold Trepper, for the express purpose of acting as cover for Soviet espionage operations in Europe that was later called the Red Orchestra by the Gestapo.

Simexco

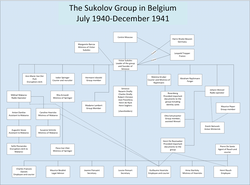

In the autumn of 1940, the Simexco firm was established by GRU officer Anatoly Gurevich. The firm was officially registered by March 1941, when it opened in two offices at 192 Rue Royale in Brussels.[1] Simexco was established as a replacement cover organisation when the Brussels rain-ware export company known as the Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company was seized after the occupation of Brussels in 17 May 1940.[2] Simexco was established as a genuine business with an absolutely firm legal status that was recognised as conservative in its approach by German service departments. On the recommendation of the administrative staff at the Abwehr IIIF. Ast. military command, it even been granted long distance, telegram communication, telephone and fax facilities by the German authorities that ensbled regular and privileged way to enable Trepper and Gurevich to communicate.[3] Gurevich became a director of the business. According to the article of incorporation, the main investor was Nazarine Drailly, a Belgian communist and informer[4], who invested 218,500 Belgian Francs in the firm.[4] Drailly was fully aware of the companies true purpose and actively took part in operations.[4] Drailly's brother, Charles Drailly, a banker, became a commercial director of the firm in March 1941. He was almost certainly aware of the nature of the firm, but maintained his distance in his role as a director, never taking part in espionage operations.[4] Margarete Barcza who lived with Gurevich, found additional shareholders amongst her bridge club.[5] These shareholders were Florida nightclub owner, Robert Christen, travelling salesman Jean Passelecq, publisher Henri de Ryck and friend of Gurevich, Henri Seghers who owned a cigarette factory.[5]

Simex

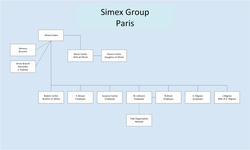

In autumn 1941, Simex opened its office, in two rooms above the Le Lido next to the Champs-Élysées in Paris,[6] and opposite the offices of Organisation Todt, the German military engineering organisation, who would become its best customer.[7] Its name was a metonym for S for Societe, IM for Import, EX for Export and was established to be a large company offering civil and military engineering contract services, general dealership and materials for Nazi German contracts resulting from the occupation.[8] The funding used to created the company was monies salvaged by Jules Jasper from the rain-ware company in Belgium, along with additional funds that were provided by the Soviet intelligence.[8] Although Trepper became one the directors of the firm and used the alias Monsieur Jean Gilbert when talking to any of the employees, it was the businessman, Leon Grossvogel who was the Managing Director.[9]

In December 1941, Jaspar left to run the Simex branch on the Rue Dragon in Marseille, French commercial director Alfred Corbin took over.[10] Corbin, an experienced businessman, has been recruited by Hillel Katz who was secretary at Simex.[10] Katz was Trepper's assistant and had known his since Trepper was in Palestine.[11] Both Corbin and Jaspar were unaware of the espionage nature of Simex. On 20 November 1941, when Jaspar was arrested, he stated he thought he was working for British intelligence.[12]

Expenses

Both the Simex and Simexco companies flourished and made substantial profits in return.[13] In 1941, the net profits of both Simex and Simexco reached 1,616,000 Francs and in 1942, 1614000, after the costs of running the network were deducted.[13] Trepper kept strict accounts as he had to submit them to Moscow for audit.[13] His group were paid in Dollars, the traditional currency used by Moscow for their agents.[13] In 1939, Trepper received 350 dollars a month, but this was cut to 275 dollars a month, when his wife and children were to Russia. His agents, Makarov, Gurevich and Grossvogel each initially received 175 dollars a month, before it also upped to 275 dollars.[13] Trepper also had to account for monies spent in each location where there was a network. From 1 June to 31 December, Trepper spent 5650 dollars in Brussels and 9421 dollars in Paris.[13] These were only daily expenses. Trepper used to the money earned from Simex and Simexco to spend lavishly. This spend included bribes and money spent for the upkeep of the Château de Billeron[13] and large daily expenses to maintain the veneer of a successful businessman. Trepper kept the accounts locked in a large clock in house at Verviers.[13] To insure against financial ruin, he kept a special reserve of monies in the form of 1000 gold dollars in jars at a house of a trusted agent.[13]

Discovery and arrest

In 13 December 1941, the German radio counterintelligence organisation, Funkabwehr, discovered the safehouse apartment at 101 Rue des Atrébates in Brussels, that led to the arrest and among others of Gurevich's radio operator, Red Army Lieutenant Anton Danilov.[14] Gurevich himself hid in the house of Nazarin Drailly to evade the Gestapo, while he made arrangements to transfer ownership of the organisation to Drailly, [14] before leaving for Paris in the same month. When he left, Drailly took over management of the firm and who actively passed military and industrial intelligence to the Trepper espionage organisation.[15] On the November 1942, the offices of Simexco was raided by the Gestapo after several months of surveillance.[5] The Simex office in Paris was raided in the same month.[16]

When the Gestapo entered the Simexco office they found only one person, a clerk,[17] but managed to discover all the names and addresses of Simexco employees and shareholders from company records.[17] Over the month of November, most of the people associated with company were arrested and taken to St. Gilles Prison in Brussels or Fort Breendonk in Mechelen.[18] Some people managed to avoid early capture, like Drailly, but who was eventually captured on 6 January 1943. His daughter Solange Eva was also arrested, but was released due to lack of evidence. Drailly was tortured with dogs that ripped his legs to shreds and they had to be amputated.[18] The prisoners in St. Gilles were sent to Berlin by train,[18] and taken to Gestapo HQ at Mauthausen concentration camp for further interrogation, before execution in Plötzensee Prison. The Nazi German tradition of Sippenhaft, meant than many family members of the accused were also arrested, interrogated and executed.[19]

References

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945. Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 33. ISBN 0-89093-203-4.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 272-273. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 262. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 21. ISBN 0805209522.

- Bertram M. Gordon (15 November 2018). War Tourism: Second World War France from Defeat and Occupation to the Creation of Heritage. Cornell University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-5017-1589-1. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 14. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 161. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 263. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. pp. 25–28. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Léopold Trepper (1995). Die Wahrheit: Autobiographie des "Grand Chef" der Roten Kapelle. Ahriman-Verlag GmbH. p. 194. ISBN 978-3-89484-554-4. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 247. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 331–332. ISBN 0805209522.

- Pine, Lisa (1 June 2013). "Family Punishment in Nazi Germany: Sippenhaft, Terror and Myth". German History. 31 (2): 272–273. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghs131. ISSN 0266-3554.