Siloam inscription

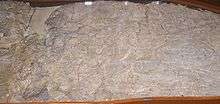

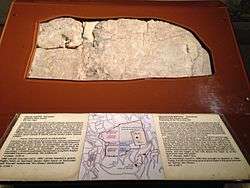

The Siloam inscription or Shiloah inscription (כתובת השילוח) or Silwan inscription, known as KAI 189, is a passage of inscribed text found in the Siloam tunnel which brings water from the Gihon Spring to the Pool of Siloam, located in the City of David in East Jerusalem neighborhood of Shiloah or Silwan. The inscription records the construction of the tunnel, which has been dated to the 8th century BCE on the basis of the writing style.[1] It is the only known ancient inscription from the wider region which commemorates a public construction work, despite such inscriptions being commonplace in Egyptian and Mesopotamian archaeology.[1]

| Siloam inscription | |

|---|---|

The inscription in its current location | |

| Material | Stone |

| Writing | Paleo-Hebrew |

| Created | c. 700 BCE |

| Discovered | 1880 |

| Present location | Istanbul Archaeology Museums |

| Identification | 2195 T |

It is among the oldest extant records of its kind written in Hebrew using the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet,[2][3][4] a regional variant of the Phoenician alphabet.

The inscription is at permanent exhibition at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

History

The tunnel was discovered in 1838 by Edward Robinson.[5] Despite the tunnel being examined extensively during the 19th century by Robinson, Charles Wilson, and Charles Warren, they all missed discovering the inscription, probably due to the accumulated mineral deposits making it barely noticeable. According to Easton's Bible Dictionary,[6] in 1880 a youth (Jacob Eliahu, later Jacob Spafford[7]; see Horatio Spafford) swimming or wading through the tunnel, discovered the inscription cut in the rock on the eastern side, about 19 feet into the tunnel from Siloam Pool. The inscription was surreptitiously cut from the wall of the tunnel in 1891 and broken into fragments which were recovered through the efforts of the British Consul and placed in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.[8][9]

The ancient city of Jerusalem, being on a mountain, was naturally defensible from almost all sides but its major source of fresh water, the Gihon spring, was on the side of the cliff overlooking the Kidron valley. The Bible records that King Hezekiah, fearful that the Assyrians would lay siege to the city, blocked the spring's water outside the city and diverted it through a channel into the Pool of Siloam.

Biblical references

2 Kings 20, 20: "And the rest of the events of Hezekiah and all his mighty deeds, and how he made the conduit and the pool, and he brought the water into the city, they are written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Judah."

2 Chronicles 32, 3–4: "And he took counsel with his officers and his mighty men to stop up the waters of the fountains that were outside the city, and they assisted him. And a large multitude gathered and stopped up all the fountains and the stream that flowed in the midst of the land, saying, "Why should the kings of Assyria come and find much water?""

Translation

As the inscription was unreadable at first due to the deposits, Professor Archibald Sayce was the first to make a tentative reading, and later the text was cleaned with an acid solution making the reading more legible. The inscription contains 6 lines, of which the first is damaged. The words are separated by dots. Only the word zada on the third line is of doubtful translation—perhaps a crack or a weak part.

The passage reads:

- ... the tunnel ... and this is the story of the tunnel while ...

- the axes were against each other and while three cubits were left to (cut?) ... the voice of a man ...

- called to his counterpart, (for) there was ZADA in the rock, on the right ... and on the day of the

- tunnel (being finished) the stonecutters struck each man towards his counterpart, ax against ax and flowed

- water from the source to the pool for 1,200 cubits. and (100?)

- cubits was the height over the head of the stonecutters ...

The inscription hence records the construction of the tunnel; according to the text the work began at both ends simultaneously and proceeded until the stonecutters met in the middle. However, this idealised account does not quite reflect the reality of the tunnel; where the two sides meet is an abrupt right angled join, and the centres do not line up. It has been theorized that Hezekiah’s engineers depended on acoustic sounding to guide the tunnelers and this is supported by the explicit use of this technique as described in the Siloam Inscription. The frequently ignored final sentence of this inscription provides further evidence: "And the height of the rock above the heads of the laborers was 100 cubits." This indicates that the engineers were well aware of the distance to the surface above the tunnel at various points in its progression.[10]

While traditionally identified as a commemorative inscription, one archaeologist has suggested that it may be a votive offering inscription.[11]

A diagram of a transcription of the Paleo-Hebrew of the inscription is available at this link.

Possible exhibition in Israel

In 2007, Jerusalem Mayor Uri Lupolianski met with Turkey's ambassador to Israel, Namık Tan, and requested that the tablet be returned to Jerusalem as a "goodwill gesture".[12] Turkey rejected the request, stating that the Siloam inscription was Imperial Ottoman property, and thus the cultural property of the Turkish Republic. President Abdullah Gul said that Turkey would arrange for the inscription to be shown in Jerusalem for a short period.[13]

See also

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

- Archaeology of Israel

- Biblical archaeology

- Shebna inscription

- Ophel inscription

References

- Lemche 1998, p. 47; quote: "A good case can be made on the basis of the paleography to date the inscription in the Iron Age. The inscription itself, on the other hand, does not tell us this. It is only a secondary source, which in this case may be right but which can also be wrong, because nobody can really say on the basis of this anonymous inscription whether it was Hezekiah or some other Judean king from the eighth or seventh century who constructed the tunnel. As it stands, it is the only clear example of an inscription from either Israel or Judah commemorating a public construction work. As such it is a poor companion to similar inscriptions not least from Egypt and Mesopotamia."

- "Siloam Inscription". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906.

- "THE ANCIENT HEBREW INSCRIPTION OF SILOAM". 1888.

- Rendsburg, Gary; Schniedewind, William (2010). "The Siloam Tunnel Inscription: Historical and Linguistic Perspectives". Israel Exploration Journal. Retrieved 2015-05-02.

- Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible [1990] 484

- Siloam, Pool of at Easton's Bible Dictionary

- Jerusalem. The Biography, Simon Sebag Montefiore, page 42, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2011, ISBN 9780297852650.

- The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) states: "The inscription was broken in an attempt made to steal it; but the fragments are now in the museum at Constantinople; and from casts that have been taken, copies of which are in Paris, London, and Berlin, it has been possible to gain an exact idea of its arrangement and to decipher it almost entirely."

- Lawson Stone, What Goes Around: The Siloam Tunnel Inscription, 20 August 2014, accessed 6 April 2018

- Sound Proof

- R.I. Altman, "Some Notes on Inscriptional Genres and the Siloam Tunnel Inscription," Antiguo Oriente 5, 2007, pp.35–88.

- "J'lem mayor turns Turkey on tablet". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- Peres, Gül'den tablet istedi

Bibliography

- Conrad Schick, "Phoenician Inscription in the Pool of Siloam", Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement, 1880, pp. 238–39.

- Archibald Sayce

- "The Inscription at the Pool of Siloam," Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement 13.2 (April 1881): 69–73 (editio princeps)

- "The Ancient Hebrew Inscription Discovered at the Pool of Siloam in Jerusalem," Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement 13.3 (July 1881): 141–154.

- H. B. Waterman, The Siloam Inscription, The Hebrew Student, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Jun., 1882), pp. 52–53, Published by: The University of Chicago Press

- Archibald Sayce, Claude Reignier Conder, Isaac Taylor (1829–1901), Samuel Beswick (1822-1903) & Henry Sulley (1845–1940), "The Ancient Hebrew Inscription Discovered at the Pool of Siloam," Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement 13.4 (Oct. 1881): 282–297.

- Claude Reignier Conder, "The Siloam Tunnel", Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement, 1882, pp. 122–31.

- Hermann Guthe, "Das Schicksal der Siloah-Inschrift" ZDPV, 1890.

- E. Puech, "L'inscription du tunnel de Siloie", RB 81, 1974, pp. 196–214

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Siloam inscription. |