Siege of Weinsberg

The Siege of Weinsberg took place in Weinsberg, in the modern state of Baden-Württemberg, Germany, which was then part of the Holy Roman Empire. The siege was a decisive battle between two dynasties, the Welfs and the Hohenstaufen. The Welfs for the first time changed their war cry from "Kyrie Eleison" to their party cries.[4][5] The Hohenstaufen used the 'Strike for Gibbelins' war cry.[6]

| Siege of Weinsberg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

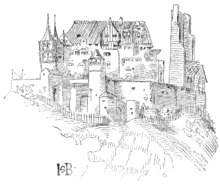

16th-century depiction of the "loyal wives" episode | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Conrad III of Germany | Welf VI | ||||||

On the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Lothair II in 1137, Henry the Proud was the Welf heir of the patrimony of his deceased father-in-law, and possessor of the crown jewels. He stood as a candidate for emperor, but the local princes opposed him and elected Conrad III, a Hohenstaufen, in Frankfurt on February 2, 1138.[5] When Conrad gave the Duchy of Saxony to Count Albert the Bear, the Saxons rose in defence of their young prince, and Count Welf of Altorf, the brother of Henry the Proud, began the war.[5]

Exasperated at the heroic defence of Welfs, Conrad III had resolved to destroy Weinsberg and imprison its defenders.[7] However he suspended the final assault after a surrender was negotiated, in which the women of the city were granted the right to leave with whatever they could carry on their shoulders.

Together the women left their possessions, and lifting their husbands onto their shoulders, headed out of town. When the king, or emperor, saw what was happening he laughed and accepted the women's clever trick, saying that a king should always stand by his word.[8] This story became known as the "Loyal Wives of Weinsberg" (Treue Weiber von Weinsberg).[5] The castle ruins are today known as Weibertreu ("wifely loyalty") in commemoration of the event.

The women's unique interpretation of the king's orders was used as a plot device in the modern movie Ever After (1998) based on the fairy tale Cinderella.

Notes

- Dallas, Eneas Sweetland (1864). Once a Week. Bradbury and Evans. p. 390.

- Женская верность (in Russian). Historico-artistic journal Solnechny veter. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- A History of Europe - Volume I. - Europe in the Middle Ages 843 - 1494. Read Books. 2008. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-1-4437-1897-4.

- Menzel, Wolfgang (1859). The History of Germany. H. G. Bohn. p. 446.

- Køppen, Adolph Ludvig; Karl Spruner von Merz (1854). The World in the Middle Ages. D. Appleton and company. p. 131.

- Kohlrausch, Friedrich (1845). A History of Germany: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. D. Appleton & Company. p. 158.

- Keen, Maurice Hugh (1999). Medieval Warfare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 80.

- Ashliman, D. L. "The Women of Weinsberg". Retrieved 24 March 2014.