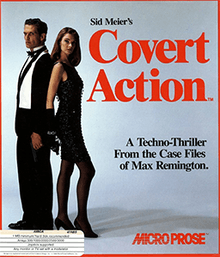

Sid Meier's Covert Action

Sid Meier's Covert Action is an action and strategy video game released in 1990 by MicroProse for IBM PC compatibles and Amiga. The player takes the role of Maximillian Remington (or his female counterpart, Maxine), a skilled and deadly free agent hired by CIA, investigating on-going criminal and terrorist activities. Tommo purchased the rights to this game and digitally publishes it through its Retroism brand in 2015.[1]

| Sid Meier's Covert Action | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | MPS Labs |

| Publisher(s) | MicroProse |

| Designer(s) | Sid Meier Bruce Shelley |

| Programmer(s) | Sid Meier |

| Writer(s) | Bruce Shelley |

| Composer(s) | Jeff Briggs |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, DOS |

| Release | 1990 |

| Genre(s) | Action, strategy |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Gameplay

The gameplay is similar to the 1987 release Pirates!, by the same developer, Sid Meier, in that the gameplay is made up of several self-directed, distinct, and unique modes of play. The controls are relatively simple and uniform, and the sound and graphics, for the period, are widely considered at or above par.

During the course of a game, the player will be tasked with installing wiretaps, infiltrating enemy safehouses, intercepting and decoding secret messages and interrogating prisoners. The plots are uniformly without distinction, as is to be expected with randomly generated text-based plot elements. This allows for a less structured story to unfold, and enhances the game's replayability.

The game is broken down into missions, with players possibly receiving promotions after each successful mission. The primary goal of each mission is to uncover details about a criminal conspiracy involving multiple parties. Players must race against the clock to discover the identities of those involved and their roles in the plot before it's too late. For example, the case might begin with blueprints being stolen for a museum. The blueprints might then be delivered from this party to another thief, who might then use them to break into a museum to steal a painting, which might then be delivered to yet another party. If the player takes too much time to uncover the details of the plan, the plot will go down successfully and the criminals will escape.

Many of the pieces of data which the player needs are gathered through various mini-games. Successfully completing a mini-game often reveals one or more pieces of data, including the names and photos of those involved, as well as locations connected to the plot. The player is allowed to decide which skills his agent has mastered ahead of time, making the associated mini-games easier.

The longest mini-game involves attempting to directly infiltrate an enemy building. Before going in, players are allowed to select their equipment, including guns, various types of grenades, and body armor. Once inside, players search desks, safes, and cabinets for clues; these are photographed using a small camera. Players also frequently confront enemy agents, who must be avoided, slain or knocked unconscious. In some cases, if the timing is right, players can find and recover major pieces of evidence (such as a stolen item). If the character runs out of health, he or she is knocked unconscious and must either lose precious time escaping, or agree to a prisoner exchange by freeing captured enemy agents.

During the cryptography mini-game, players attempt to decode a scrambled message within a certain period of time. Players are frequently given certain known letters to begin with, but must then figure out the remaining letter mappings in a simple substitution cipher. Use of existing clues from the ongoing investigation is often key to solving these, e.g., searching for a word which could be "Washington" when it is known that the plot is taking place there.

The driving mini-game may involve either the player tailing a suspect to discover a new location, or the player fleeing from chase cars in order to avoid a confrontation. Cars are represented by small dots on maze-like streets. Players use a simple interface to control speed and direction

Electronics in the game involves the manipulation of circuit boards to either perform wiretapping or vehicle tracing. In the wiretapping mini-game, players attempt to either cut or to connect current flowing through a set of power lines to a number of phone icons, in order to listen in to conversations. At the same time, players must avoid disturbing the lines connected to alarms. The game is played by re-arranging the junctions through which power flows to produce the desired results.

Development

Sid Meier was reportedly dissatisfied with the final product, because he believed that the disparate elements of the game, however good they were individually, detracted from game play. As a result, he developed what he called the "Covert Action Rule": "It's better to have one good game than two great games." He described the origins of this rule in an interview with GameSpot:

The mistake I think I made in Covert Action is actually having two games in there kind of competing with each other. There was kind of an action game where you break into a building and do all sorts of picking up clues and things like that, and then there was the story which involved a plot where you had to figure out who the mastermind was and the different roles and what cities they were in, and it was a kind of an involved mystery-type plot.

I think, individually, those each could have been good games. Together, they fought with each other. You would have this mystery that you were trying to solve, then you would be facing this action sequence, and you'd do this cool action thing, and you'd get on the building, and you'd say, "What was the mystery I was trying to solve?" Covert Action integrated a story and action poorly, because the action was actually too intense. In Pirates!, you would do a sword fight or a ship battle, and a minute or two later, you were kind of back on your way. In Covert Action, you'd spend ten minutes or so of real time in a mission, and by the time you got out of [the mission], you had no idea of what was going on in the world.

So I call it the "Covert Action Rule". Don't try to do too many games in one package. And that's actually done me a lot of good. You can look at the games I've done since Civilization, and there's always opportunities to throw in more stuff. When two units get together in Civilization and have a battle, why don't we drop out to a war game and spend ten minutes or so in duking out this battle? Well, the Covert Action Rule. Focus on what the game is.[2]

Reception

Computer Gaming World praised Covert Action for including both action and "mind-twisting brainwork", and stated that "individual cases take at least half an hour to solve, but they are addictive". The magazine criticized the poor documentation, but concluded that the game "is entertaining in the extreme", comparing it to The Fool's Errand and Starflight.[3]

See also

- Floor 13

- Spycraft: The Great Game

References

- "Purchase Agreement between Atari, Inc. and Rebellion Developments, Stardock & Tommo" (PDF). BMC Group. 2013-07-22.

- https://web.archive.org/web/19991103090659/http://www.gamespot.com/features/sidlegacy/interview12.html

- Ardai, Charles (May 1991). "Ardai Admires Meier's Spies". Computer Gaming World. p. 76. Retrieved 17 November 2013.